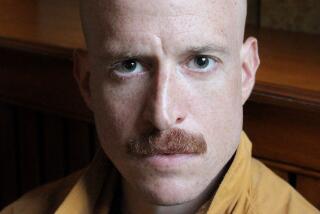

Robert A. Heinlein, Acclaimed Science Fiction Writer, Dies

- Share via

Robert Anson Heinlein, considered by many to be the most influential author of science fiction since H. G. Wells, is dead at the age of 80, it was reported Monday.

Heinlein, who had suffered from heart ailments and emphysema for a decade, died in his sleep over the weekend at his Carmel home, Charles Brown, publisher of the science-fiction magazine Locus and a friend of the family, told United Press International.

Heinlein was the winner of an unprecedented four Hugo awards, given by a popular vote of science fiction fans for best novel of the year. The four books are “Double Star” (1956), “Starship Troopers” (1959), “Stranger in a Strange Land” (1961) and “The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress” (1966). In 1975 Heinlein received the first Grand Master Nebula Award, given by the Science Fiction Writers of America for a lifelong contribution to the genre.

He was also guest commentator alongside CBS-TV’s Walter Cronkite on the Apollo 11 space mission in 1969, when Neil A. Armstrong left the first footprints on the moon.

Fellow sci-fi author Ray Bradbury has called the prolific Heinlein “a popcorn machine,” popping more ideas in half an hour than most people have in a year.

Christine Schillig, vice president and publisher of G. P. Putnam & Sons, one of Heinlein’s publishers, remembered him as “one of the founders of what we know as science fiction today.”

“He was a 50-year influence on the genre,” she said. “He was one of the original writers who created from vision, what the future should be, what it might be.”

In the “Science-Fiction Handbook,” L. Sprague de Camp reported the results of a 1953 poll of 18 leading writers of speculative fiction. They were asked to list authors who had influenced their work. Only 10 authors were mentioned by more than one of the 18, and of those 10 the only modern author was Heinlein.

Heinlein’s novel “Rocket Ship Galileo” (1947) not only signaled the beginning of the period during which he did his most popular work, it was, along with the short story “The Man Who Sold the Moon,” the basis for George Pal’s 1950 film “Destination Moon.”

“Stranger in a Strange Land” was Heinlein’s 1962 Hugo-winner and perhaps his most famous book. It is a tale of a Martian who establishes a religious movement on Earth, and its devotees over the years have come to include convicted murderer Charles Manson, a fact that mystified Heinlein to his dying days.

‘Startled’ by Reaction

Heinlein commented on this in papers appended to the manuscript when he gave it to UC Santa Cruz: “I still think it is a good story (but nothing more)--and I must confess that I am startled at the effect it has on many people. . . .”

“Stranger” also added a new word to the language--”grok” --which dictionaries define as “to understand thoroughly because of having empathy” (with). It was a word that symbolized Valentine Smith, Heinlein’s alien hero.

Heinlein (rhymes with “fine line”) sold his first story in 1939. He was inspired to write it by a $50 prize offered by Thrilling Wonder Stories. When Heinlein, born in Butler, Mo., finished the story, he decided it was too good for the contest and instead sent it to Astounding Science Fiction. The magazine’s editor, John W. Campbell Jr., bought it for $70, then encouraged Heinlein to continue writing by buying one story after another for years.

First Story

That first story, “Lifeline,” tells of a man who invents a machine that can predict the moment of a person’s death. It was the first in what came to be known as Heinlein’s “Future History,” a collection of stories with a common fictional background that extrapolates a possible future of the human race.

Science fact-and-fiction writer Isaac Asimov once said that between 1939 and 1942, Heinlein “single-handedly, under the aegis of John Campbell, lifted science fiction to a new pitch of quality.”

Heinlein was a graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, Md., where he was a champion marksman and swordsman. But in 1934, he contracted tuberculosis while serving on a destroyer and was retired at age 27 after a long recuperation. Although he never saw combat, the military was to play a large role in his thinking.

Other Professions

He then worked as an aeronautical engineer, silver-mine owner, real estate agent and architect before turning to writing.

Between 1942 and 1945 Heinlein worked as a civilian engineer in the materials laboratory of the Naval Air Material Center at the Philadelphia Navy Yard. With Asimov and De Camp, (both scientists as well as science fiction writers), he helped design high-altitude flight suits that bear a striking resemblance to the real space suits designed since. Heinlein also wrote a number of engineering textbooks during this period.

After the war, he was divorced from his first wife, Leslyn Mcdonald, to whom he had been married while in the Navy.

In 1948, he married Virginia Gerstenfeld, a woman who excelled in many fields, from biochemistry to figure skating.

‘Juveniles’ Period

Through the late 1940s and the ‘50s, Heinlein wrote what many critics believe was his best work--the so-called “juveniles.” Norman Spinrad, president of the Science Fiction Writers of America in 1980 said, “(They) were better than anybody else’s. The only thing that made these different from his other science fiction was that the protagonists were teen-agers. He didn’t write down, he didn’t patronize.”

James Gunn, a past president of the writers’ group, said in his “The Road to Science Fiction, Part 2”: “These juveniles would represent an introduction to science fiction for a generation of young people.”

Among the novels Heinlein wrote in that period are “Starman Jones,” “The Star Beast” and “Citizen of the Galaxy,” books that Peter Nicholls’ prestigious “Science Fiction Encyclopedia” says “have strong appeal for adult readers as well as youngsters, and some critics consider them to be Heinlein’s finest works.”

David Gerrold, editor, novelist and television writer, said the main thing about a Heinlein novel is that “you could believe it.”

Broke Barriers

This ability to write science fiction that was accessible to people not accustomed to reading it was one of the factors that allowed Heinlein, like Kurt Vonnegut, Harlan Ellison and a few others, to break the slick magazine barrier.

Traditionally, like most other writers of science fiction, he had been trapped in the pulp magazines. But his story “The Green Hills of Earth” about a blind poet, a Homeric figure who sang of the “spaceways,” appeared in the Feb. 8, 1947, issue of the Saturday Evening Post. In subsequent years, his science fiction stories appeared in other such unlikely places as Argosy, Town and Country, Blue Book and American Legion Magazine.

In his introduction to “Heinlein in Dimension,” writer-critic James Blish said Heinlein “is so plainly the best all-around science fiction writer of the modern (post-1926) era that taking anything but an adulatory view of his work seems to some people . . . to be perilously close to lese majesty. “

Even so, neither Heinlein nor his fiction existed without controversy. Writer-editor Gerrold said, “Heinlein has been charged with being a racist and a fascist and a sexist and none of these charges are correct. The ignorant are reading their own prejudices into his stories.”

Free-Love Advocate

Despite this, Heinlein, an advocate of free love and open marriage, found the outcry was sometimes so loud that he devoted a few paragraphs to self-defense in the book “Expanded Universe” (1981).

Heinlein’s 1960 Hugo-winner, “Starship Troopers,” is about a soldier coming up through the ranks during a war of the far future. An overtone of fascism permeates the book. In “Expanded Universe,” Heinlein said it “outraged ‘em. I still can’t see how that book got a Hugo. It continues to get lots of mail, not much of it favorable . . . but it sells and sells and sells and sells, in 11 languages. It doesn’t slow down--four new contracts just this year (1981). And yet I almost never hear of it save when someone wants to chew me out over it. I don’t understand it.”

While researching “I Will Fear No Evil” (1970), Heinlein discovered the National Rare Blood Club, an organization similar to the Red Cross that specializes in finding and dispensing rare blood. Not long after the book’s publication, Heinlein suffered a medical emergency and underwent surgery to correct a blood-flow problem. He credited the activities of the club with saving his life. Heinlein became one of the most vocal supporters of blood bank organizations, and Red Cross blood donating rooms have since been a common sight at science fiction conventions.

In 1986, Heinlein’s final work, “The Cat Who Walks Through Walls” was published. It was a tale of murder for hire and resurrected his longtime protagonist, the venerable Lazarus Long, who had walked through some of Heinlein’s earlier books over a period of 10,000 space years. His final outing, however, was dismissed in some reviews as a parody of the science fiction genre that Heinlein had made meaningful for so many.

In Part 2 of “The Road to Science Fiction,” there is this summing up of the Heinlein oeuvre.

“More than any other writer, Heinlein had the ability to present carefully crafted backgrounds, including entire societies, in economical but convincing detail. This and, at its best, his narrative drive and his spare, vigorous prose, provided science fiction with models for the authors who followed after.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.