Down to the Minute Details : Reproductions of Neon Clocks Turn Back Hands of Time

- Share via

SAN CARLOS, Calif. — Ken Baisa works full-time as an engineer, then trudges to his garage to pursue his true passion: turning back the hands of time.

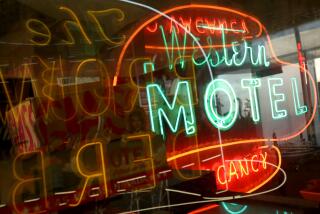

Baisa reproduces neon clocks that were the advertising rage of the 1930s and 1940s and are now making a comeback with businesses and consumers.

“There isn’t a night that really goes by that I’m not out here,” said Baisa as he surveyed the workshop where he makes replicas of neon timepieces for nostalgia lovers and Art Deco fans.

Neon signs first appeared in the United States in 1923 at a Los Angeles auto dealership. Neon clocks began showing up in the 1930s in theaters and soda fountains. A smaller, 12-inch table-top model appeared on the back bar in taverns and lounges.

Brightly Colored Clocks

Baisa, 48, has admired the brightly colored clocks since the days of his childhood in San Francisco, when he often would go to matinees and gaze at the green glow of the clock next to the movie screens.

The popularity of neon clocks came to a jarring halt in the 1950s, when incandescent and fluorescent signs appeared and television emerged as the main visual advertising medium.

But that age of neon clocks never ended for Baisa. In the late 1960s, he already had begun work at Palo Alto-based Beckman Instruments--makers of medical instruments--and spent his spare time winning motorcycle races.

But he continued to be a clock watcher.

In 1983, Baisa began to make reproductions of the clocks, based on the famous Glo-Dial line, since restoring often cost too much and old clocks were hard to find. Then he had a brainstorm--add personal messages to the clocks.

His reproductions can look just like the originals, including the precise lettering, plus added personalized sayings on the glass and two-tone colors for the neon.

“If they want something close enough and want it for another 40 years,” consumers will buy the reproductions, said Baisa, a medium-height, stocky man with a graying mustache and beard.

Logo on Each Unit

Baisa said his business logo, Ken-Glo Clocks, is printed in small letters on every reproduction so that it cannot be passed off as an original.

He reproduces five basic models of the old-style neon clocks, including the hexagon, the 12-inch table-top, the 14-inch wall mount, the “chase wheel” and the 23-inch type.

“Chase wheel” refers to neon that becomes an optical illusion, with the surrounding wheel of neon appearing to move faster as someone moves back from the clock.

Prices range from $295 to $650 for Baisa’s clocks, which are sold from a co-op store he and his wife, Sandy, belong to called Collector’s Market Antiques near his home in San Carlos, a small city 25 miles south of San Francisco.

He said his clocks are better than the originals because he has improved on the on-off switches, the painting and the chrome plating.

The art work, performed by co-worker Allen Gianoli, is also top-quality and will include whatever the customer wishes--if there’s room on the clock.

“I want somebody who’s going to pay that kind of money to be proud of it,” Baisa said, admitting that he enjoys hearing customers’ compliments when they come to pick up their prizes.

Don’t expect Baisa to quit his job any time soon so he can make oodles of clocks and reap higher profits. “That’s not the fun of it,” he said. “Everything I do is like creating something again.

“You start getting people mass-producing them, it won’t be the same,” he said. “They’ll be like jukeboxes. They won’t be a collectible.”

Photographs Each One

His clocks are such one-of-a-kind creations that he takes a photograph of each one before shipping it off to the customer. He’s received orders from as far away as England, France, Japan and West Germany.

One 23-inch clock still in his garage--his workshop shares space with a 1934 Ford car he has been planning to restore for four years--belongs to San Francisco 49ers owner Eddie DeBartolo Jr.

The red-orange clock reads “San Francisco 49ers World Champions Super Bowls XVI, XIX, XXIII” around the glass.

Baisa said DeBartolo wants it for his trophy room.

“I went more for authenticity than I did for production,” he says of his reproductions. “I want people to think this is a 10-plus. I got to make them like they were.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.