New Tool in Drug War: Money Laundering Newsletter

- Share via

MIAMI — Business executives, bank officers, lawyers, real estate brokers and even car dealers have been drafted into the war on drugs--whether they like it or not.

Armed with stiff new regulations passed under the Bank Secrecy Act of 1988, the IRS and other federal agencies are forcing businesses and financial institutions to help track the estimated $220 million in profits generated daily by illegal drug sales in this country.

“All that cash does no good stored in boxes. They have to turn it around. That necessarily involves legitimate businesses,” said Miami lawyer Charles Intriago, who has started a publication that promises to make sense of the regulatory maze and keep subscribers on the right side of the law.

“The government has conscripted the entire business community and required them to submit their paper trails,” Intriago said. “It’s saying, ‘OK, you’re in the war now--play by the rules or face severe penalties.’ ”

Money Laundering Alert is an eight-page monthly newsletter of advice, statistics and reports on what criminals do to hide the source of their money and what government is doing to uncover their schemes.

As trade journals go, Alert has a sizable niche, says Intriago, a former chief counsel for the House committee that oversees all banking regulatory agencies. He has also prosecuted white-collar criminals and drug traffickers while an assistant U.S. attorney in Miami.

Amid growing calls for the legalization of drugs and evidence that interdiction efforts have failed to reduce the cocaine flowing into this country, money laundering controls have become the government’s weapon of choice, Intriago said.

“The money laundering initiative has a higher probability of success than the others, such as interdiction. It hits the profit motive,” he said.

Enlisting the help of banks and other, often unwitting, handmaidens to drug traffickers has yielded impressive results.

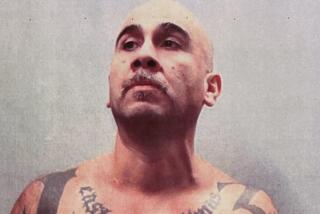

Days before billionaire Medellin cartel enforcer Gonzalo Rodriguez Gacha was gunned down in Colombia on Dec. 15, U.S. and Swiss officials traced his profits and were able to freeze $61.8 million of his assets in several countries.

Under money laundering laws, banks are required to report large cash transactions. Soon, the Treasury Department could also force banks to put names and addresses on the estimated $1.25 trillion transferred daily around the world on telephone lines. Details of that initiative are laid out in Alert’s November issue.

These new money laundering laws are in their infancy, and many have yet to be enforced. Many otherwise law-abiding businesses may be unaware of the penalties they face, Intriago said.

Alert costs $295 a year, but Intriago notes that the Treasury Department can now impose $500 fines for every negligent error a bank teller makes on one of the required forms.

“Tell me these institutions wouldn’t like to receive a publication that could spare them thousands of dollars in fines, to say nothing of the bad publicity,” Intriago said.

With the fourth issue going to press, Alert has more than 200 subscribers, ranging from banks, thrifts and credit unions to lawyers and accountants, foreign governments and diplomatic offices.

Intriago doesn’t mention “drug kingpins” on his list, and he bristles at the suggestion that his newsletter could be as useful to criminals as to law-abiding citizens.

“We don’t do criminal background checks on our subscribers, nor does the Wall Street Journal,” he said. “A number of criminal defense attorneys have subscriptions, however.”

One of those attorneys sits on the newsletter’s editorial board as well: Neal Sonnett of Miami, who represented Panamanian Gen. Manuel Antonio Noriega when he was indicted on drug trafficking charges in Florida.

“He’s a very respected attorney,” Intriago said, “no matter what his clientele is.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.