Letting a Little Air In : AT WEDDINGS AND WAKES, <i> By Alice McDermott (Farrar, Straus and Giroux: $20; 213 pp.)</i>

- Share via

Get the subatomics right and you get the universe right; get the quarks in line and the quintessentials fall into place. So modern physics tells us, pausing periodically to wonder if it is true.

There are a few American writers who use the homely details of people’s lives and behaviors that way. They get these details absolutely right, not for the purpose of description, or classification, or--as with some of the minimalists--taxidermy, but to ignite the transformations inside them.

Ann Tyler does it frequently in her shabby-genteel Baltimore; Bobby Ann Mason did it at least once, in the small Kentucky town of “In Country”; Susan Minot did it, also once, with the troubled New England family of “Monkeys.” Alice McDermott did it with “That Night.” She got the movements and vacancies of an American suburb to work so exactly that, out of their clotted energy, she released a Tristan and an Iseult in the guise of two adolescent lovers.

McDermott does it once more in “At Weddings and Wakes.” A more constricted book in some ways, it is set, in the 1950s, among the stifled grievances of an Irish-American matriarch and her three spinster stepdaughters. Cooped up in the middle-class solidity of a Brooklyn apartment--Brooklyn was solid back then--they alternately fatten on rancorous memories and struggle ineffectually to escape them.

Mary Towne came over from Ireland in the 1920s to help with her sister’s fourth childbirth. When the baby was born, the sister died; Mary stayed on to help the widower, and eventually to marry him. Briefly, there was a blaze of something like passion; then the widower died, leaving Mary to rule with the heavy hand of disappointed memory.

John, their son and her pride, turned into a drunk, moved away and comes back annually for a brief, angry visit. As for the stepsisters, the loving and sweet-tempered May entered a convent, found she loved its peace and quiet so much as to distract her from religion--a wonderful McDermott touch--and came home to live. At the end, she marries Fred, a postman, but it is a sadly brief escape. Agnes, with a good job as an executive secretary in Manhattan, returns each night to exercise her critical spirit and sharp tongue. Veronica, pock-marked and alcoholic, drifts woozily out of her bedroom long enough to locate an affront and carry it back in with her.

The Towne apartment--heavy furniture and Waterford crystal and starched Irish linen for holidays--is asphyxiating, and McDermott occasionally comes close to asphyxiating us with it. (It is a risk you take if you write well; describe a Camembert, and the reader has to open a window.) But essentially, her book transforms the oppressiveness.

The somber realism of the Towne menage is undermined by the little eyes that see it. They belong to the three children who visit dutifully twice a week during the summer from their home in the leafy green outskirts of Queens. Lucy, their mother, brings them; she is the fourth stepdaughter. Ostensibly, she has escaped; in fact, with her incessant visiting, her perpetual phone calls, her instant immersions into the latest round of Towne bickering, she is torn between two worlds.

The Brooklyn apartment is old-world memory troubled by the struggle of its prisoners. The new world and its possibilities are represented by Lucy’s husband: kind, buoyant and with a talent for exploration and enjoyment. The children move forward with him, inevitably and fortunately, but at some sacrifice. McDermott makes us feel the health that lies in releasing memory’s chains. She makes us feel the weight of the chains, but she makes us feel their piety as well, and the tug they exert even when cast off. Her book has a bewitching complexity.

The narration is part of the bewitchment. It belongs to the three children: kind Bobby, who at 12 or so still thinks he wants to be a priest; gawky and introspective Margaret, with a gloomy touch of her mother’s “easy access to regret”; and Maryanne, the wide-eyed, melodramatic baby of the family. The narrative doesn’t belong particularly to any one of them, though Margaret is the most likely, and it suggests both children seeing, and remembering as adults what they once saw.

This allows reflectiveness and immediacy; it allows a darting chronology, and a darting selection of events to be followed. It allows us, as children do, to change the subject. Its quickness and lightness do not lighten the heaviness of the Towne household, but they set it off like alternating tiles in a mosaic.

We read of the painful twice-weekly trip of Lucy and the children from Queens to Brooklyn: a 10-block walk in the July heat, a bus, then another bus, a subway and then another subway. Yet the painfulness--it lies not so much in the trip as in the quality of Lucy’s dogged pilgrimage to her family’s battles--is relieved by the freshness of the children’s experiencing. They note Lucy’s fuss with the front-door latch as they leave, her juggle with white gloves, handbag and the cigarette she lights up between buses and stamps out with the toe of her high heel pumps. In the crowded bus she stands, shielding them “in what might have been her shadow had the light been right, but was in reality merely the length that the warmth of her body and the odor of her talc extended.”

After the long Brooklyn afternoon, their father arrives to take them home. They all perk up: the children, Lucy, her sisters, old Mrs. Towne. Gaiety has made an entrance, theatrical as the contrast between the masks of comedy and tragedy. The trip back in the family car is another contrast, a chariot ride after the morning’s bus-and-subway ordeal.

Another chapter tells of the annual two-week beach holiday in a rented cabin on the eastern tip of Long Island. The Brooklyn visits are replaced by swimming, shell-collecting and fishing from a hired rowboat. It is the father’s time. A slum child who remembers what a trip to the country meant to him, he insists on the two-week break to administer beauty as though it were a vitamin. Lucy enjoys it in a complaining sort of way; but each evening she treks to the public phone to plug back in to Brooklyn, and the quarrelsome remembrance that is her own vitamin.

There are stories of each of the Townes, and beautifully, lightly contrasting accounts of the children’s own encounters at school and elsewhere. The most vivid and winning of the Towne stories is that of May, the ex-nun who timidly falls in love with Fred, the postman, and marries him. It is a lovely courtship, though it comes tragically late. The wedding and reception are a long and skillful set piece, but their awkward celebration and embarrassing emotional misfires belong to an all too familiar genre, and don’t advance it much.

On the other hand, the story of Fred is one of the most rousing and moving things in the book. It uses familiar materials--he is an Irish-American bachelor who cares for his mother until her death--but his portrait continually takes on new and unexpected shadings. McDermott can make sadness exhilarating; she can make goodness as irresistible as venial sin.

The detail in “At Weddings and Wakes” is not painstaking but hallowing; as if specific descriptions were the wards of a key and lock that, fitted exactly, open the door to the perilous magic of the past.

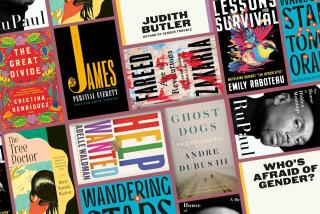

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.