New Work Rules Follow Hepatitis A Outbreak : Epidemiology: County restrictions may affect hundreds. Activists for the developmentally disabled had protested earlier, broader order.

- Share via

ORANGE — Responding to an outbreak of hepatitis A among 17 developmentally disabled people, health officials issued work restrictions this week that may affect hundreds of people in an effort to control the spread of the disease.

The order is aimed at anyone who has had contact with residents of community care facilities for the developmentally disabled and who work in jobs handling food or utensils. It also includes developmentally disabled workers who care for children or the elderly.

The order, by the Orange County Health Care Agency, could jeopardize the employment the developmentally disabled people have worked to get, advocates for the disabled said Friday.

But the order represents a compromise of sorts. Developmentally disabled clients and their advocates had objected vociferously to a more sweeping version issued Thursday by the county health officials, calling the directive discriminatory and dangerously broad.

That order would have applied to every client of Regional Center of Orange County--which provides services to 7,500 developmentally disabled people--who worked in a food-service establishment, whether or not they actually handled food. It also would have applied whether or not a client had any recent contact with other developmentally disabled people.

The new order, worked out late Friday, more clearly defines the population at risk of spreading hepatitis A as those who have had contact within the past six weeks with developmentally disabled people living in community care facilities.

“We do not want to cause undue harm,” said Dr. Hildy Meyers, an epidemiologist of the Orange County Health Care Agency who worked on narrowing the order. “We don’t want people losing their jobs for no reason. We don’t want people to be stigmatized. What we are trying to do is stop transmission of the disease as quickly as we can.”

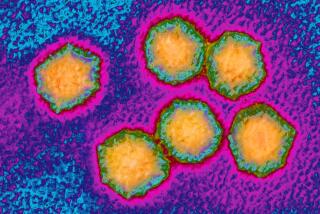

Hepatitis A is a virus affecting the liver that is present in the feces of infected people. It is most often spread to others by hand-to-mouth contact or eating contaminated, uncooked food. Symptoms may include fatigue, a mild fever, nausea, vomiting, dark colored urine, and yellow eyes or skin. Symptoms generally develop within a month of exposure and can range from mild to severe. Some people do not ever develop symptoms, and death from hepatitis A is rare. The order issued Friday requires clients in specific job categories to prove, through a blood test, that they already are immune to the disease or to undergo vaccination with a formula approved just weeks ago by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Those who are vaccinated must wait two weeks after their first dose before returning to their jobs.

The county Health Care Agency has ordered 1,200 doses of vaccine, at a cost of $66,000, and will pay for the first shot in the two-shot series, said Dr. Hugh Stallworth, the county’s director of public health.

Health officials said immediate and decisive action was necessary because their initial efforts to contain the outbreak--first reported in February--were not successful. They tried to head off illness among exposed clients with an antibody serum known as gamma globulin, but some cases were identified too late for the injections to be effective.

“We have a responsibility to prevent the spread of disease into the community,” Meyers said.

The outbreak initially occurred among members who attended various “workshops” in which dozens of developmentally disabled people gathered to perform tasks as a group. Hepatitis was reported among clients from six or seven different workshops.

To date, 14 cases have been reported among developmentally disabled clients and three cases are classified as “probable” cases.

Officials became alarmed when they discovered earlier this week that a client who worked at a restaurant was infected. That person washed his hands and wore gloves and apparently did not endanger the health of customers eating at the restaurant, Meyers said, so no public health alert was issued in response to his case.

But authorities were concerned because the case signaled the danger of the outbreak’s spread into the community at large, Meyers said. Meyers said health officials would show this degree of concern in any outbreak, regardless of who was affected. She said health officials were concerned about the spread in the disabled community because it appears to be “close-knit,” with frequent contact among members.

But she cautioned that hepatitis A cases in Orange County are most often associated with day-care centers and with travel in foreign countries, not with developmentally disabled groups. Forty-eight cases of hepatitis A were reported through February; last year’s total was 354. Earlier Friday, at a contentious meeting at the Orange-based Regional Center, developmentally disabled people and their advocates sharply condemned the Health Department’s more sweeping order, arguing it would violate the civil liberties of developmentally disabled people. Job placement specialists said they have enough trouble placing clients without having to explain to employers that they must cease work for a while because of an infectious disease.

“Due process has been thrown out the window,” said Guy Leemhuis, a client rights representative with Protection and Advocacy Inc., which is based at the Regional Center.

“I don’t think you have any right . . . to keep us away from our jobs,” said Mary Buck, 31, of Mission Viejo, a developmentally disabled woman who has worked at a sandwich shop for about a year.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.