AIDS Researchers Savor Gains in War Against Virus

- Share via

WASHINGTON — The end of 1986 was a heady time for AIDS researchers, who finally had found a drug, called AZT, that seemed to have an impact on this unforgiving new disease.

A decade later, AZT and its sister drugs, while still having an important role, have now become supporting players to a new generation of compounds that is 50 to 100 times more powerful.

This, along with the development of more sophisticated tests that measure the AIDS virus, and a growing body of scientific knowledge about the workings of the disease, have left AIDS specialists more upbeat than at any time in their frustrating battle against this disease.

“We’re looking at a time when things have changed substantially,” said Dr. Robert T. Schooley, program chairman of the Third Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections that ended here Thursday. “It’s no longer a question of whether things will change but how quickly.”

Mindful of many disappointments, scientists have tempered their optimism with caution, saying that the ultimate proof can only come over time. But they are closer than ever to finding the right drug combinations to keep the disease in check--although not cure it--and predicted even more effective new drugs on the horizon.

“Progress is in the eye of the beholder,” said Dr. Douglas Richman, an AIDS specialist from UC San Diego. “If people think we’re going to have a cure, they’re being unrealistic. But we’re making major strides. The data we are seeing are showing incremental accomplishments that exceed anything we’ve seen to this time. But we have to see how this plays out and how they benefit patients over time.”

Schooley said that advances in basic science--that is, a better understanding of how HIV operates in the body and how the body responds to it--have given scientists better tools to make research judgments and will enable clinicians to make more informed treatment decisions for their patients.

For example, one important piece of work released this week showed a distinct relationship between high levels of virus in the body and the rapid onset of symptoms.

“We have so much more of a substantial picture of how this disease is brought about by HIV and we can actually measure virus much better in people,” Schooley said. “Taking that, with improvements in drugs, and drugs with new mechanisms of action, we will have an even greater ability to see how well they do in patients.”

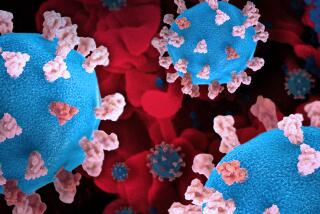

While gains in understanding the basic science of the human immunodeficiency virus have gone steadily uphill since the epidemic began in 1981, therapeutic progress has been more like a ride on a roller coaster.

In the epidemic’s early years, before AZT, scientists despaired of ever finding an antiviral that could fight this insidious virus. When AZT came along, they were ecstatic, but its effectiveness, while valuable, turned out to be temporary.

AZT, and other drugs from a family known as nucleoside analogs, were just not enough. The virus quickly produced mutant strains of itself that could resist the drugs.

Researchers grew gloomy again, until late 1994, when preliminary evidence of a new generation of compounds, called protease inhibitors, showed a startling impact on the first small number of patients who had taken them.

And this week, in the strongest evidence yet, scientists reported that these drugs can dramatically inhibit the virus, prevent or delay AIDS-related illnesses and prolong life.

“We’re again in a very exciting time,” said Dr. Paul Volberding, director of the AIDS program at San Francisco General Hospital, who was one of the principal investigators years ago for AZT. “I remember being excited about AZT--and that was a drug far less potent than the ones we’re exploring now. Now we’re seeing combinations of drugs that can be both durable--and potent.”

The meeting did not focus on developments in AIDS vaccines, which would prevent transmission of the virus, a topic that is slated to be the subject of a conference later this month at the National Institutes of Health.

But scientists pointed out that the pace of AIDS vaccine development is nowhere near as great as that of therapeutics. “We’re a long, long way from a vaccine,” Schooley said.

Nevertheless, scientists left the conference buoyed by good news on the treatment front, predicting more advances to come. Even now, researchers are studying even newer and more novel approaches to thwart the reproduction of the virus, considered critical to controlling the disease.

To suppress replication, the virus must be hit in combination punches, at different stages of its reproductive cycle, to prevent mutant strains and drug resistance. This is why multiple therapy is considered crucial and why only one drug does not work well alone.

Patients improved for a time on AZT, until resistance developed. Today, most researchers believe that AZT and other drugs like it, when used with protease inhibitors, will make the effects of the protease drugs last longer.

Nucleoside analogs act at an early stage by curbing the production of an enzyme known as reverse transcriptase, which the virus uses to turn RNA--its genetic material--into DNA. Protease inhibitors hit the virus later, blocking the production of an enzyme known as protease. The virus needs this chemical to break up two large protein strands; the pieces are essential to making copies of new infectious virus. If proteins are not chopped up, the job will not be done.

Researchers are even now beginning to look at second-generation protease inhibitors. And they are also studying another class of compounds, called integrase inhibitors, which prevents the virus from inserting its genetic material into the DNA of the body’s cells, yet another part of the cycle.

Dr. John Leonard, director of the antiviral research program for Abbott Laboratories, developer of one of the new protease inhibitor drugs likely to go on the market soon, said that even more effective drugs are yet to come.

“We can do better,” he said.