‘Exhibit A for the Power of Prayer’

- Share via

Among the estimated 500,000 people in the United States who struggle each year to recover from brain injuries, Ryan Corbin might be the most famous.

Eighteen months ago, the eldest grandson of singer Pat Boone accidentally crashed through his Brentwood apartment building’s skylight and plunged 40 feet to the concrete floor. He fractured his skull, broke his jaw, and ruptured his spleen. As paramedics arrived, Corbin, then 25, stopped breathing.

Since then, his slow but steady healing has been called miraculous -- in Christian magazines and supermarket tabloids, from church pulpits, on Web sites and on four “Larry King Live” shows on CNN, including a Christmas special that airs today.

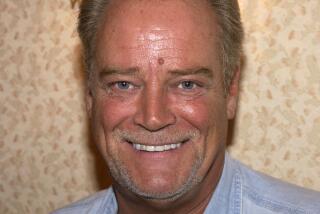

“He’s Exhibit A for the power of prayer,” said Boone, a crooner and movie star who became popular in the 1960s for his baby-faced looks, white shoes and gospel songs. “You can only attribute his recovery, in light of the medical prognosis, to God.”

The fascination with Corbin’s recovery goes beyond his minor link to celebrity.

For those who believe, Corbin’s healing illustrates the efficacy of prayer and serves as a testament to the tens of thousands of messages spiritually transmitted throughout the world to God for the 26-year-old’s healing.

And today marks another milestone in Corbin’s story: his first Christmas at home since the accident.

“This is certainly the best Christmas I’ve ever had,” said Lindy Michaelis, Ryan’s mother and the daughter of Pat Boone, sitting in her Coto de Caza home in south Orange County. “He’s living with us, he knows who we are, he knows his life has purpose. Seeing him, it’s easy to point to a loving God.”

Of course, giving God credit for what some consider to be a miraculous healing leaves open the question that has nagged the faithful for ages: What about those who don’t get healed, despite the prayers of many?

“If we knew why everything happens the way it does, then we’d be as smart as God,” said Rick Warren, Corbin’s pastor and founder of Saddleback Church in Lake Forest.

“But we’re not God, so we have a limited capacity for understanding the big picture.”

Within days of Corbin’s accident, family members asked Christians through churches and on the Internet to pray for his recovery.

Ryan’s father Doug Corbin set up a hotline with daily recordings so people could pray for his specific needs. And Boone went on “Larry King Live” to ask viewers around the world to pray for his grandson.

“We got prayers by the millions from all over the world,” Boone said.

After the first King appearance, Boone said he wondered: “What do you think the apostle Paul or Peter would give for the opportunity that we just got: to go into 220 nations and have 50 million people watching?”

Family members said doctors informed them that Ryan would mostly likely remain in a vegetative state the rest of his life.

Boone remembers one day when a neurologist showed him a CAT scan of Corbin’s brain. He asked the doctor about the large black pattern that covered most of its brain’s surface.

“The doctor said, ‘That’s atrophy,’ ” Boone recalled. “ ‘And that’s permanent.’ ”

Family members did get doctors to concede that brain injuries are notoriously fickle, and the brain can bypass permanent damage by rewiring itself. But Boone said the physicians always warned them, “Don’t get your hopes up.”

Today Corbin is just beginning to talk in whispers, a few words at a time, after an 18-month medical ordeal that included six hospitals, four operations, 36 units of blood, doctors who asked family members to consider when they wanted to shut down his life support system, five months in a coma, and hundreds of hours in rehabilitation therapy.

A 6-foot-4 former basketball star at Irvine High School who was president of his Pepperdine University fraternity, Corbin remains in a wheelchair, his left arm curled tight against his body.

He’s not paralyzed, but the signals from his brain have been jumbled enough that connections have been lost and need to be reestablished.

These days his progress is measured in tiny increments. On Monday, for instance, he started biting his nails again.

“You broke that habit; let’s not start that again,” Michaelis teasingly tells Ryan, bringing a smile to his face.

“He laughs and jokes now,” said Mark Desmond, director of Tustin-based High Hopes, a head-injury program that Corbin attends twice a week. “He’s a miracle. Can you attribute that to God? Yes. To great family support? Yes. And to his faith and people who have been praying for him all over the world.”

Academic research over the last decade that tried to determine the efficacy of prayer in healing has produced mixed results and wide debate within the medical community.

A 1998 double-blind study at the California Pacific Medical Center in San Francisco showed that AIDS patients did better when strangers prayed for their health. Studies at the Mid America Heart Institute in Kansas City, Mo., and at Duke University showed that cardiac patients who were prayed for experienced fewer serious health problems.

But critics point to research at the Mayo Clinic and at Columbia University that found no connection between healing and prayer.

They also criticize the research methods of many of the studies and doubt that the effect of prayer, even if it were real, could be scientifically measured.

For Corbin’s family, the studies don’t matter. As part of his speech therapy, Michaelis has him recite with her the words of Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew: “With God, all things are possible.”

To them, prayer has brought him this far. Boone even sees God’s hand in the speed of his grandson’s recovery.

“God could do it instantly, but it’s quite clear it’s going slowly,” said Boone, believing that the long recovery has allowed thousands to witness the healing.

“Everywhere I go, people ask, ‘How’s Ryan? How’s he doing?’ People have just taken a universal, personal interest in him,” and are seeing through him the “simple goodness and grace of God.”

What the public doesn’t see is the earthly toil involved in Corbin’s rehabilitation: the spoon-fed meals. The mixing of a “cognitive drug cocktail” that is poured through a stomach tube. The building of ramps and remodeling that allowed Ryan to move back home. His groans in the middle of the night when he needs to turn over. The mother singing to her 26-year-old son who mouths the words as a toddler would. The understanding of his brother and sister who now get less attention from their parents. The neighbors and church members who volunteer to make meals or run errands.

“When people ask the question, ‘Where is God in this tragedy?’ I tell them to look around at all the Christians helping, praying, supporting, caring, and loving the family -- that’s where God is,” said Pastor Warren. “He’s in the hearts of his people, using their hands, their feet, and their abilities to show God’s love in practical ways.”

Before the accident, Ryan was a devout Christian. An aspiring writer, he wrote an unsold screenplay called “Threesixteen,” a modern version of the story of Jesus.

And his evangelical zeal was a major factor in the conversion of his stepfather -- a self-proclaimed “hardheaded agnostic” -- to Christianity two years ago.

Both his mother and grandfather recalled conversations shortly before the accident in which Corbin told them he felt God was about to use him “in a big way.”

Now, as Corbin recovers amid worldwide attention, they both wonder whether this was part of God’s plan.

“I didn’t look at [the publicity] as a great thing at first,” Michaelis said. “No way I wanted to go on television and bear my pain.

“But what an opportunity we have to show God at work.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.