For generations of kids, he was Captain Kangaroo

- Share via

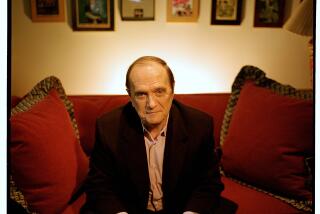

Bob Keeshan, better known as Captain Kangaroo, died Friday at age 76, and that he wasn’t older seems to have been a matter of general surprise -- the impression being that he was a geezer from the day he first threw open the doors of his Treasure House, in October 1955. He was only 28, in fact, but he had already been Clarabell the Clown on “Howdy Doody,” Corny the Clown on “Time for Fun” and Tinker the Toymaker on “Tinker’s Workshop.” Many years later, he took a turn as “Mister Mayor” on a short-lived Saturday-morning series. But the Captain is who he was born to be.

Captain Kangaroo’s Treasure House is the first world other than my own that I can remember inhabiting, the screen that separated us as psychically permeable as Alice’s Looking Glass. A nice man in a coat of many pockets (hence “Kangaroo”), wearing a bowl haircut and a big mustache (prosthetic at first, real later), Keeshan spoke directly to the viewer -- not to the camera, but through the camera. There was no peanut gallery screaming behind him, no kid actors throwing their dimples in your face. He was there for you alone.

In those long-ago days when mothers stayed home and children ran free until kindergarten, the Treasure House was my personal nursery school. Keeshan read stories -- which I remember as always being “Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel,” “Make Way for Ducklings,” “The Story About Ping” or “The Seven Chinese Brothers” -- and made things out of construction paper. Mr. Green Jeans (the late Hugh “Lumpy” Brannum), who represented the rural element to the Captain’s relative urbanity, would drop by with interesting animals.

Accompanying them was a cast of creatures whose names were simple statements of fact -- Mr. Moose, Bunny Rabbit, Grandfather Clock, Dancing Bear (next to Barney, a marvel of decorum), all the work of puppeteer Cosmo Allegretti. The puppets were tricksters -- the mute Bunny Rabbit was Harpo to the highly verbal Mr. Moose’s Groucho -- but the worst that would come of their plotting was a rain of pingpong balls, or the surrender of a carrot. It was a big moment when Grandfather Clock woke up, or Dancing Bear danced. “An abundance of excitement is not good,” Keeshan told writer Gary H. Grossman. “The gentlest children’s show on the air,” is how CBS advertised “Captain Kangaroo” on the eve of its premiere. Even then, Keeshan was beating against the tide -- a Zen alternative to the racket of Pinky Lee, Soupy Sales and Buffalo Bob.

The familial reality of the Treasure House gang was certainly heightened by the fact that its members saw one another nearly every day for decades. The length of Keeshan’s run on network TV -- 29 years -- is astonishing, and unparalleled, and will certainly remain so. It’s almost impossible to imagine CBS now or ever ceding a daily hour of prime morning air time to a children’s show; indeed, Peabody and Emmy awards notwithstanding, CBS moved more than once to cancel it, only to be chastened by public outcry.

Generations of viewers came and went, on the way from rattles to razors, each preserving a memory of the Captain as its own -- like James Hilton’s famous Mr. Chips (who, as Robert Donat played him, resembled the Captain not a little). The Treasure House was remodeled some over the years, and a few new characters, like the health-wise Slim Goodbody, were introduced, but the show always remained quiet and calm, an hour to ease you into the day: the kiddie equivalent of a cup of coffee and the Sports section.

Today’s child sees the world differently, of course, through eyes trained to speed by music videos and video games and the stroboscopic intensity of modern television advertising. Keeshan ran a commercial enterprise as well -- at least until he moved to PBS in the early ‘90s -- but he vetted the sponsors, favoring products that he felt were actually good for his audience. A member of the board of education in West Islip, N.Y., for five years, he cared more about kids than about marketing, or market share.

Every generation longs for the slower pace of its childhood, to be sure, but something more has been lost here. What has disappeared from children’s programming with the passing of Bob Keeshan, and of Fred Rogers, is the human face -- or rather, the adult human face, that of the trustworthy parental, or grandparental, surrogate. At a time in which a grown man showing interest in children is reflexively viewed with suspicion, this is somehow not surprising, but it was different once. L.A. natives of a certain age will remember Engineer Bill and Sheriff John and Tom Hatten, although every municipality with its own station had its equivalent, who addressed viewers in tones of gentle authority and real respect. They have been muscled aside by robot baby-sitters and corporate pitchmen, and the world is the worse for it.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.