Serial Killer Coolly Admits His Guilt

- Share via

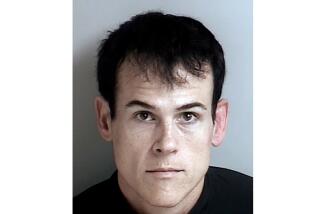

WICHITA, Kan. — His gaze direct, his voice steady, a hint of pride in his chilling words, former Boy Scout leader Dennis L. Rader pleaded guilty Monday to murdering 10 people to satisfy his sexual fantasies, acknowledging that he was the serial killer who called himself BTK.

Named for his technique -- bind, torture, kill -- BTK terrorized this city from 1974 through early this year, killing men, women and children of all ages and boasting about it in a series of catch-me-if-you-can communications with police and reporters.

On what was to have been the opening day of his trial, Rader, 60, described the killing spree to his victims’ relatives and others in a quiet courtroom. The former code compliance officer for the suburb of Park City -- once the respected president of his church congregation -- calmly detailed each of the murders, which he called his “projects.”

“There is a sense of horror. Simple and complete horror,” said Cindy Duckett, a close friend of victim Nancy Fox.

In a voice so dispassionate that he might have been discussing the tulips in his garden, Rader talked of hanging an 11-year-old girl in her basement, of rearranging the clothes on a 62-year-old woman he had just strangled, of spreading a parka under a 38-year-old man to ease the pressure on his broken rib so he’d be comfortable while Rader asphyxiated him.

He broke into 24-year-old Shirley Vian’s house at random, he told Judge Gregory Waller, because he was “all keyed up” after another planned assault fell through. Rader said he told Vian that he “had a problem with sexual fantasy” and would need to tie her up. First, though, he tied up her children.

“They started crying, so I said, ‘This isn’t going to work,’ ” Rader said. “We took the kids to the bathroom and she helped me put some toys and blankets and other odds and ends in the bathroom. We tied the door shut and took another bed and shoved it up against the door.”

With the kids trapped, he tied Vian to the bedposts. She threw up. “I got her a glass of water and tried to comfort her a bit,” Rader said. Methodically describing his actions, Rader told the judge: “I put a plastic bag over her head ... and used a rope to strangle her.”

All the while, Vian’s children were banging on the bathroom door, screaming.

Rader left them there as he gathered the ropes he had brought with him and slipped out of the house.

“This guy is demonstrating what a real sociopath is like,” said retired Det. Arlyn Smith, who tracked BTK in the 1970s. “These [victims] were like furniture to him. He talked about ‘putting them down’ as though they were dogs.”

Rader, who is married and has two grown children, is to be sentenced Aug. 17. He will not face the death penalty because the crimes were committed before Kansas had a capital punishment statute. But if his sentences run consecutively, he will probably die in prison.

Rader told the judge he had no history of mental illness; his lawyers said they had considered an insanity defense but decided they had no grounds.

“All these incidents ... occurred because you wanted to satisfy a sexual fantasy, is that true?” Waller asked.

Rader answered, “Yes.”

The 45-minute confession, presented with no trace of remorse, was met Monday with a mixture of relief and revulsion. Many in Wichita said they were glad to be spared the expense and uncertainty of a trial. They were relieved to know that BTK would never kill again. Yet the details of Rader’s double life left them appalled and bewildered.

Though his voice was flat, Rader seemed to use the jargon of his obsession with some pride, as he spoke about his “hit kit” and his “hit clothes,” his code-named victims, his “death strangle.”

“It’s still beyond my comprehension that a human being is capable of something like that, and then to talk about it so coldly, so matter-of-factly, with no flinching and no emotion,” said Paul Carlstedt, who served alongside Rader in the leadership of Christ Lutheran Church.

“What I felt was this: Can I kill you now?” said retired police Lt. Charles Liles.

Standing straight in a cream-colored jacket and tie -- trim thanks to a jailhouse regimen of push-ups -- Rader presented the image of a man very much in control.

But his confession revealed a serial killer who had fumbled his way through many of his murders.

Several times he left a victim for dead, only to be surprised a few moments later when she “woke up,” having passed out during the strangulation. He had to double-back to one crime scene after leaving his gun in the victim’s house. Another time, he planned to use the victim’s pickup to make his getaway, then realized that he had stolen the wrong set of keys, so he had to flee on foot.

Several of his victims fought ferociously; one, Kevin Bright, managed to escape after Rader shot him twice and left him bleeding on the floor, apparently “down for good,” Rader said.

“It was a total mess,” he told the judge in a low-key, conversational tone. “I heard Kevin escape. The front door was open and he was gone.”

In that assault, as in a few others, Rader forgot to bring his hit kit -- a briefcase containing ropes and other tools, he told the judge. Instead, he improvised restraints that his victims were able to break. “If I had brought my own things, Kevin would have probably died,” he told the judge. “I’m not bragging on that. It’s just a matter of fact.”

Shot in the head, Bright was never able to give police a detailed description of his assailant. The other witnesses to the attacks were all children, also unable to give an accurate description of BTK.

But detectives who tracked BTK obsessively for decades said luck was only part of the reason Rader had eluded capture for so long. After listening to him recount one inept attack after another, they said his lack of planning actually made him harder to find.

“Sometimes the bumbling idiots are the hardest to track,” Smith said.

“You’re always looking for a common thread among the victims. But it turns out there was a genuine randomness. He was so disorganized, there was not a pattern of any kind,” the former detective said.

Rader did not talk about why he had taunted law enforcement with letters and phone calls, or why he stopped killing after the murder of Delores E. Davis in 1991.

Nor did he explain why he resumed sending reporters puzzles and clues in March 2004.

But Rader did answer some of the mundane questions that over the years have troubled police and the many armchair detectives sifting through the case.

He confirmed speculation that, at least in one instance, he had gained access to a victim’s home by posing as a telephone repairman. He even brought along tools to pretend to check the line. He drove his own car to most of the attacks, usually parking a few blocks away. He carried a gun and used it to gain control.

Rader said he chose his victims at random, after months or years of “trolling” for likely candidates. “I had a lot of them,” he said. “If one didn’t work out, I moved to another.”

The only one he knew before attacking her was Marine Hedge, who lived a few doors down from him. He knew her from working in the yard, he said, “a neighborly type thing.”

He gathered information about the others by stalking them. When he chose Fox, 25, as a target in 1977, he got her name from her mailbox; he watched when she came and went; he even stopped by the jewelry store where she worked “to size her up.”

In a tone that edged toward arrogance as he lectured the judge on the behavior patterns of serial killers, Rader explained, “The more I knew about a person, the more I felt comfortable.”

Listening to the confession, Fox’s friend said she was glad to know the details -- but also disturbed beyond measure.

“Am I supposed to forgive him?” Duckett asked. “Probably. But right now, I don’t know.”

Jeff Davis, the son of Rader’s final victim, Delores Davis, told reporters: “Mom’s still gone. At the very best, it’s a hollow victory.”

The details of Rader’s confession unsettled many of the victims’ relatives, some of whom had not known precisely how their loved ones died.

They learned that Julie Otero, 34, had pleaded in vain for her son’s life. That Hedge, 53, had been stripped, her body brought to a church parking lot and posed in various bondage positions. That Vicki Wegerle, 28, broke free of her restraints and put up such a loud fight that the dogs in the backyard wouldn’t stop barking.

“Nothing can prepare a family member to hear these facts,” Sedgwick County Dist. Atty. Nola Foulston said. “They are distressed. And it is very difficult for them.”

Foulston said she was not surprised by Rader’s lengthy recitation in court. “Mr. Rader,” she said, “wants to be in control.”

Other BTK experts suggested the same motivation for his plea.

They noted that BTK had always sought publicity. He demanded a nickname for himself; he chided the press for not writing more about his crimes; he left notes, word games and packages of clues around town. One of those packages led to Rader’s arrest in February: It contained a computer disk that police traced to his Christ Lutheran Church.

“He’s so self-centered and narcissistic, he always wanted people to know he had done this,” said Robert Beattie, a lawyer who just finished writing a book on BTK. “He wanted to join the elite group of serial killers.”

Even while in jail, Rader has craved attention.

He compulsively cataloged all his letters from reporters and the public. “Your letter was number 202 received so far,” he wrote to an old friend, George Martin. “I have written back to most. My hand tends to numb at times.” On the envelope, he scribbled a word puzzle -- much like those BTK used to bedevil police -- and a poem about his “wounded heart.”

Rader called a local TV station last week to complain that the pressure was “about to rip me open.” Speaking often in the third person -- and sometimes using the plural “we” -- Rader went on to say that his wife, Paula, was considering divorcing him and that his contact with his two grown children was “hit or miss.” He complained that he hadn’t had a haircut in nearly two months.

Rader also corresponded with a Topeka woman who had said she hoped to write a book about him. Under Kansas law, neither Rader nor his relatives can profit from such a venture.

“But it’s never been about profit,” Smith said. “It’s about him. It’s about his ego. It’s about getting his story out, with his spin on it. Now he’s free to do it.”

*

Huffstutter reported from Wichita and Simon from Denver.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.