Beleaguered Iraqi Police Maintain Sense of Honor

- Share via

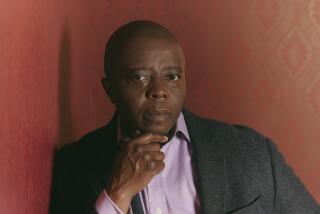

BAGHDAD — Scar tissue from shrapnel runs like a shiny thread above Jawad Ali’s ear. It rises like a blister on his thumb. His skin is a diary of these brutal streets. He slipped out of his bulletproof vest the other day and pulled down his collar, exposing a bullet wound from an insurgent attack on his way to work.

“I was interviewed on Iraqi TV five months ago,” said Ali, a 19-year police veteran with a wife and four daughters. “The insurgents must have seen me and identified me. The next morning when I came toward the station, I was shot in my civilian clothes. These days I’m afraid of nothing but God. It is our manhood that keeps us coming to work.”

Iraqi police move through a terrifying rhythm of car bombs, gun battles, kidnappings, exploding rockets and shallow mass graves holding tangles of handcuffed men with bullet holes in their heads. The nation has spiraled into a confusing grid where crime, insurgency and intensifying sectarian attacks are overwhelming a poorly equipped police force trying to keep order in a whirl of smoke and rage.

U.S. military helicopters whir overhead, soldiers hunker on the streets, and police officers are wedged between a war and a new nation struggling with democracy. Police stations have become tense outposts marked by barricades, barbed wire and grenade scars from insurgents who count anyone in uniform as a collaborator with Washington.

One moment a patrolman can be chasing a thief with a sack of stolen flour, and the next be standing amid bloody streaks left by a suicide bomber.

For men like Ali, the silence between the two is brief. He accepts the job because there are few others. But it’s more, he says. It’s about honor. It’s about being a 39-year-old man with a missing front tooth, who has maybe one more chance to marry off his last two daughters and guide his country toward a place where there are fewer coffins balanced on the tops of cars.

Still, it’s best not to say you’re a cop. Badges and commendations are kept locked away from neighbors who might whisper something into Iraq’s eerie web of gossip. Every officer knows that each time he clicks on the siren and flashing lights, he may be going to stop a crime, but he’s also a blaring advertisement for an insurgent ambush.

At least 487 police officers have been killed and 1,258 wounded in Baghdad since the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime on April 9, 2003, according to government statistics. That accounts for about 12% of the city’s police force of 15,000.

These figures do not include dozens of special police commandos and the hundreds upon hundreds of men killed by car bombs and insurgent raids while waiting to sign up at police recruiting centers.

“I’ve already received two threatening letters from the mujahedin,” said Ghassan Ali, a 23-year-old patrolman. “They warn me to leave my job, otherwise they will hurt me and my family. My mother and my wife tell me to quit the police. But if we all listened to our wives and mothers, who would do our work?”

Ghassan Ali and his partner, Hasan Kadum, sat the other day in a restaurant, spooning out rice and chicken and deciphering walkie-talkie static.

Ali, light-skinned and the taller of the two, wore a wrinkled, pale blue shirt. Kadum wore silver sergeant bars on his sturdy shoulders, his pistol polished. They sweated and traded stories. They remembered officers who had died, and the times they almost did. They half-smiled at the fact that they earn about $240 a month and have to buy their uniforms.

Like most Iraqi police officers, they say it’s too dangerous to wear their uniforms to and from work. Kadum hides his in a plastic bag.

“The insurgents set up a false checkpoint and stopped my bus a few months ago,” said Kadum, a 24-year-old with the wisp of a mustache. “I squeezed my uniform tight and hid it between the front seat and the driver’s seat. I tucked my police ID in my sock. Life is like this. We have no choice but to face it.”

Kadum doesn’t like to melt away like that, to scrunch himself up like his uniform until danger passes and his bus moves on. He bristles at the humiliation, stores it up, shares it with his buddies at the station, many of whom have their own ways of making their uniforms hidden and small. But when their uniforms are on and their bullets are loaded, they say they fear only God. It is the kind of bravado that’s needed.

“We got a call not long ago to respond to the house of a government minister, I won’t say who,” Kadum said. “There was a suspicious car in the neighborhood. A guy was driving a car bomb and was going to wait outside the house until morning and kill the minister. But it was raining and the car got stuck in the mud and the terrorist fled. We walked up to the car. The windshield wipers were still going.

“We looked through the rain and dust. There were explosives and artillery shells. We ran away and called the bomb squad.”

On a different day, another car exploded in front of Jawad Ali in the Dora section of Baghdad.

Ali has many stories. He and his team took their lunch break in a different restaurant. He sat on a plastic chair as lamb was grilled over an open fire and tomatoes and pickles were served on dented plates. Nicked and splintered Kalashnikov rifles rested on tables next to forks. Some of the men were quiet, some couldn’t stop talking. They were behind a high concrete barricade, safe, most believed, from the reach of the streets.

“The streets are tricky,” Ali said. “We get a lot of false calls. Sometimes the seeker of help is your enemy. We are targeted for ambushes and bombs. I have seen many men die.”

They were in the restaurant only a few minutes when a walkie-talkie crackled: A suspected suicide bomber was prowling the neighborhood. Plates were abandoned. Jawad Ali refastened his bulletproof vest.

The officers waited outside for another call. None came and the sky stayed quiet. They returned to their meals; the waiter stoked the fire and brought new cups of tea.

“My old commander, 1st Lt. Ali, always kept pliers in his pocket,” Jawad Ali said as other men gathered. “He liked to disable bombs. He tried to defuse a roadside explosive and it killed him. We were standing 50 meters away and we pleaded with him not to go near it.

“Things are more dangerous today. We don’t have enough weapons and our supply flow is bad. Look at me, I’m a warrant officer without a pistol. I have a Kalashnikov, but I turn that in when my shift is done. I go home at night unprotected.”

Policemen like Jawad Ali and Ali Mahmood are jealous of the higher-paid soldiers in the Iraqi national guard. The way the police view the violent landscape, they face the same dangers soldiers do. Patrolmen work 12-hour shifts, and many of them dread the curfew between 11 p.m. and 5 a.m., when an insurgent might call to say his wife is having a baby, only to set a trap for the responding ambulance and police car.

“A national guardsman can get about $300 a month,” said Mahmood, who was trained by U.S. instructors after the war. “But a lot of police earn much less. Our enemies are armed with heavy machine guns, sniper rifles, rocket-propelled grenades and car bombs.”

“I was a cop under the tyrant Saddam Hussein,” said Jawad Ali, who is happy to be rid of the dictator but is a bit bewildered at the cost. “It was safer to be in the force back then.”

Sgt. Kadum said it was tough to find anonymity these days. Eyes watch from everywhere. Sides, he said, have been chosen, and it seems to take the skill of a magician to slip out of a police life at the end of the day and venture the dangerous route home as a civilian. His one place of sanctuary used to be a barbershop at the rim of the city, where he and other officers and national guardsmen would meet just after dawn to steel their solidarity before beginning their shifts.

Insurgents cased the barbershop. They hid a bomb under a bench. Two men died.

Times staff writer Suhail Ahmed contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.