When the Neighbor Is a Rapist

- Share via

SHASTA LAKE, Calif. — Andy Coulter’s eyes widen as he spies the red pickup. Cruising a wooded back road outside town, he glares into his rear-view mirror and hits the brakes on his old Ford, ready to pull a U-turn.

He’s convinced he’s spotted James Richard Perkins, an eighth-grade dropout and convicted rapist. Perkins has been identified by the state as “high-risk,” the most serious category for paroled sex offenders. Before his 24th birthday, he sexually assaulted one woman and raped another, having kidnapped both from shopping mall parking lots. He went to prison in 1984.

Since Perkins was paroled to Shasta Lake last fall, Coulter has pursued him like a dogged amateur detective. He frequently checks with store clerks to see whether the ex-con violated parole by purchasing alcohol. He cruises by the rapist’s yellow ranch house, slowing to a crawl. When Perkins is outside, he stares him down before moving on.

Now, on a sunlit February afternoon, he steps on the gas, satisfied that the pickup doesn’t belong to Perkins after all. “You get paranoid,” he says. “Every time you see a red truck, you think it’s him.”

Perkins’ half-brother lobbied state parole officials to bring Perkins to Shasta Lake. He says he thought he could help his kid brother create a new life.

Now, he says the 43-year-old man he calls “Jimmy” feels as though he has traded one prison cell for another.

“Do you think I’d allow him to live under the same roof as my wife if I wasn’t convinced he was a different person?” says the brother, who asks to remain anonymous, convinced that the release of his name would fuel more of the harassment he’s already suffered.

Perkins is among 4,500 sex offenders paroled each year from state prisons -- an average of 17 each workday. Most are men, with regrettable pasts and worrisome futures, rejoining a society disturbed by their presence.

Today, 102,000 registered sex offenders are scattered throughout California. Statistically, four in 10 will commit a sex crime again.

Many released sex offenders embark on relatively anonymous existences in big cities. Others, like Perkins, end up in places like Shasta Lake, population 9,700, where he has upset the social balance, causing bitterness in a place that prides itself on its rural friendliness.

Many residents, including Coulter, the town’s ex-mayor, feel abandoned by law enforcement, left alone to battle a baffling criminal enigma. Some have moved beyond anger to something more ominous.

Councilman Ray Siner promised at a public meeting to use “my Smith & Wesson” to protect his family.

“We can’t be responsible for what happens to this guy,” says Coulter. “For his own safety, they need to get him out of here.”

Getting a Quiet Start

Perkins arrived quietly last October in Shasta Lake, about 100 miles south of the Oregon border, not far from majestic Mt. Shasta.

He fell into an easy routine, doing yard work during the day, playing acoustic guitar or watching TV in his room at night. He liked “Fear Factor” but criticized “Law & Order” for too often featuring sex offenders.

Within a week or so, his brother persuaded a friend to hire Perkins as a carpenter.

Perkins’ parole, which ends in spring 2006, requires him to be home by 8 p.m., stay within 25 miles of his brother’s house, and wear an electronic bracelet so authorities can track his movements. Three times a week, he attends counseling sessions and meets regularly with his parole officer.

In Shasta Lake, Perkins initially waved at neighbors and offered to help at least one with her chores when her husband wasn’t around.

“She called this guy ‘the nicest man you’d ever want to meet,’ ” recalls Jerry Garber, the husband.

But Garber didn’t like how his new neighbor wouldn’t make eye contact. “I told my wife, ‘That character’s got skeletons in his closet.’ ”

Garber wasn’t the only one with suspicions. Shasta County Sheriff’s Det. David Heberling recalls that a state parole agent warned him in November that Perkins should be considered a high risk to rape again.

“He said it was a not a matter of if, but when,” Heberling said.

The parole officer did not return telephone calls for comment. And Sharon Jackson, a regional parole administrator, discounted that version of events. “I find that hard to believe,” she said, adding that she would not “authorize staff to say” such a thing.

Later, Heberling faced Perkins at a meeting with the offender at sheriff’s headquarters: “How can you convince me you aren’t going to re-offend?”

“I’m 20 years older now,” Perkins reportedly replied. “People change over time.” Perkins declined to be interviewed for this story, citing parole restrictions.

Unconvinced, sheriff’s officials considered issuing a rare public safety warning. State law requires parole officials to notify county officials when an offender is released into their jurisdiction. Local officials can then decide whether to make the arrival public.

“I didn’t want to get a phone call at 2 a.m. and have to face some mother and father whose daughter he assaulted and admit that I knew beforehand he was here,” said Capt. Dave Compomizzo.

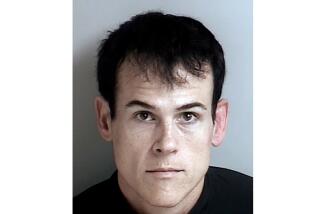

The sheriff’s office issued a press release Nov. 5, warning that the county’s latest sex parolee “may re-offend.” The advisory gave a brief description of Perkins’ crimes and included the ex-con’s mug shot, describing him as 5 feet 9 and a stocky 220 pounds, with blond hair and blue eyes.

The release said deputies wanted to help residents “protect themselves against known sex offenders.”

That changed everything.

A Wrenching Memory

Andy Coulter was listening to talk radio that Friday afternoon when he heard the news about James Perkins. The story was carried every half hour by radio stations, and local TV featured Perkins as the lead news item that night.

Jerry Garber and his wife were at the post office when they recognized the mug shot of the man whose reluctant gaze had made Garber uneasy. “Oh, look, it’s Mr. Perkins,” Garber recalls his wife saying.

For Coulter, the rapist’s arrival conjured up angry memories. In the 1970s, his 14-year-old daughter was raped by a local man who later went to prison.

Coulter got counseling for his daughter, but not himself. For years, the 75-year-old retired food market owner dreamed of revenge. “You know how they castrate sheep?” he asks, the words delivered like body punches. “I know it would have gotten me into trouble. But that’s what I would have done.”

Now another sex offender had moved painfully close to Coulter’s home in Ranchera Pines, an isolated 55-home tract where he lives with his wife. Coulter stewed for days.

The Town Meets

On Sunday night, Nov. 14, 2004, nine days after Shasta County sheriff’s officials issued their warning about the rapist, residents crowded into a red-brick fire station to decide what to do about James Perkins.

The meeting was held by Coulter, who had teamed up with a group of concerned retired women to make phone calls and circulate fliers. Sheriff’s officials faced the crowd, answering questions about Perkins and offering a few details of his crimes.

As townsfolk met inside, Perkins and his brother drove by the firehouse to investigate the commotion. The men eyed the packed parking lot and kept moving.

The day after the Sunday night meeting, parole agents searched Perkins’ house after residents reported he had purchased beer, a violation of his parole. They found nothing.

Soon the simple rhythm of town life changed. Women were afraid to take their daily strolls. “If you relax, something may happen,” resident Barbara Cross said.

Others began a letter-writing campaign: “We are a rural county in Northern California. Our law enforcement personnel cover hundreds of thousands of square miles.... “ homeowner Gracious Palmer wrote to the state Department of Corrections. “We do not have the resources to monitor this high risk sex offender and protect our public safety.”

Adults weren’t the only ones worried. Kids were rattled too. At the Sunday meeting, teen-aged girls fought back tears, prompting school officials to soon relocate a school bus stop so students didn’t have to pass the ex-con’s house.

Coulter didn’t feel any better after the firehouse session. He didn’t like how deputies had stressed Perkins’ right to privacy. “This guy’s got more rights than we do,” he says. “He’s the one who’s been in jail. And we’re harassing him by driving past his house?”

He felt betrayed. Deputies issued the public warning that unsettled the town, he says, then sat back and did little else than warn residents “to behave ourselves or they’d put us in jail.”

If deputies wouldn’t keep an eye on Perkins, Coulter would do it for them. He and others pledged to monitor the ex-con and report what they saw. Few took the job more seriously than Coulter.

“There’s no cure for a guy like this,” he says. “He’s going to commit again. I want to make sure it doesn’t happen in my community or near my house. So I’m watching him all the time.”

Covering the town in his 1992 truck with the Velcro dashboard and wooden cup rack, Coulter began his search for the red pickup. He made a point to pass by the offender’s yellow ranch house at least once or twice a day.

Throughout November, Perkins ignored the cars that crept past his house. “He accepted who he is a long time ago,” his brother says. “He’s numb to the whole thing.”

The brother wanted to write to neighbors, but decided not to feed the fire: “You get angry when people plot behind your back but don’t have the guts to say anything to your face.”

Inside the house, Perkins slowly opened up to his sister-in-law about the darker elements of his past. But she already knew. She had often accompanied the family to see him in prison. Years later, when her husband finally confided why Perkins was behind bars, she read the court file and psychiatric evaluations.

Perkins grew up in the working-class Bay Area suburb of Richmond and by age 12 was already smoking pot and injecting heroin and methamphetamine. At 14, he pulled a knife and forced a 51-year-old neighbor, the wife of a police officer, to drive to a secluded cul-de-sac. Perkins announced he wanted to rape her, but she called his bluff: “All right, let’s do it right now.” The boy backed down.

A court declared Perkins a juvenile delinquent and he was eventually sent for drug rehabilitation. He soon dropped out of school and accumulated a police record of petty burglaries.

On Dec. 29, 1978, Perkins accosted a woman in the parking lot of a Sonoma County mall. High on meth, and wielding a hunting knife, he drove the 28-year-old victim down an isolated dirt road. He sexually assaulted her, stopping only when she mentioned her boyfriend.

“I can’t do this,” he said, according to court records. “You seem like too nice a girl.”

Driving her back, he asked her out on a date.

After his trial, Perkins was sent to the Atascadero State Hospital for treatment as a mentally disordered sex offender.

Upon his release five years later, he moved to San Jose to work at an ice house, still with a drug habit. On a Saturday in April, 1984, less than a year after leaving Atascadero, Perkins confronted a 23-year-old woman at a mall parking lot, using a pellet gun to force her into his car.

He took her to a nearby home, where he slapped her face and raped her. Then he smoked pot and watched TV. Once alone, the woman managed to call police, who arrested Perkins. He was sentenced to 43 years in prison.

Behind bars, Perkins taught computer repair classes and listened to rape survivors tell how the attacks scarred their lives. He kept a diary on his hair-trigger temper.

He wanted to prove he was more than just a junkie and rapist. “Remorse is not something you do and are finished with,” he told a counselor. “I feel it every day.”

His brother began visiting the inmate more often. They decided Perkins would move to Shasta County when paroled in 2003.

“I look at Jimmy and can’t believe he did all those things,” says the sister-in-law, who asks not to be named. “He’s so cool now.”

But residents didn’t buy the notion that Perkins was “cool.” Terry Steels says her 14-year-old boy used Perkins’ mug shot as a target for knife-throwing practice. James Hayes says his 18-year-old daughter was afraid to go into the kitchen at night because the windows faced Perkins’ home.

By Thanksgiving, Perkins was dating a Redding home care worker who had known him as a young man. She saw his mug shot in the local newspaper and drove to Shasta Lake to find him, asking neighbors, “Where does that rapist live?” On weekends, they began taking fishing and biking trips.

After the new year, a flier circulated calling Perkins’ brother “an inconsiderate, self consumed, lousy neighbor” with such epithets as “pariah, persona non grata, the jerk on the block” and “the man without a conscience.”

The brother briefly considered moving but decided not to give neighbors the satisfaction. He hasn’t ruled out suing them for harassment: “It seems like they’re trying to push Jimmy over the edge,” he said.

By late February, trouble spilled into the workplace where Perkins worked as a carpenter. One co-worker had started calling him “Rapo.” Then a customer recognized Perkins and asked the owner about him.

Soon, Perkins was laid off. For weeks, he waited to be called back to work. “Jimmy’s naive,” said the brother, who recently found him other work. “I finally told him he was never going to get hired back, that people will say anything to get you out the door.”

Not everyone in Shasta Lake detests Perkins. Laverne Mattson says people are too quick to judge. “He spent 20 years in prison,” says the widow. “Maybe he learned his lesson. Unless people have walked in his shoes, they shouldn’t crucify him.”

But Coulter won’t let his guard down. He still scouts for the red pickup. At one Tuesday church choir practice, when talk turned to Perkins, Coulter’s pastor counseled tolerance. “He says you’re supposed to hate the sin but love the sinner,” says Coulter. “I know I’m supposed to forgive, but I just can’t.”

A Different Meeting

One day Perkins’ brother decided that the community harassment had gotten so bad that he complained to Sheriff’s Lt. Denis Carroll, who then offered to arrange for him to meet with neighborhood leaders to clear the air.

When Coulter got wind of the plans, he papered the neighborhood with fliers and once again knocked on doors. “If he wants to meet with the community, he’s got to meet with all of us,” Coulter said of the brother.

Some 75 people showed up at another fire station, so many that officials had to move the two fire engines to fit them all in. But Perkins’ brother was not among them. Deputies had warned him to stay away, saying they could not guarantee his safety. So the brother hired a local attorney, Stewart Altemus, to attend the meeting.

“You leave him alone and he’ll leave you alone -- that’s all we’re asking,” Altemus said of Perkins. “He has the right and the obligation to be where he is. And there’s not anything you or anyone else can do about it.”

“So we’ve got no rights?” a man said.

“You can move,” Altemus shot back.

“Not if we can’t sell our homes, we can’t,” said another.

Jack Vandagriff said his daughter was too afraid to come home from Los Angeles for Christmas.

“We’ve been raped too,” he said. “You talk about rights. Don’t I have a right to see my kid, Mr. Attorney?”

“Buy a plane ticket,” the lawyer called out.

“We did that,” Vandagriff said, his anger rising. “We went to see our daughter and spent Christmas at a Denny’s. It stinks. Thanks to Perkins.”

Siner, the councilman, asked people not to let their fear “get inside your heads. Think what you’re doing to your neighbors -- and yourselves.”

His words sank in. “Amen,” somebody said.

Stalemate

One day in early March, Perkins lost his resolve. Watching the town’s turmoil, he told his brother: “They’re using you to get to me.”

He asked parole officials to move him. They refused. Perkins’ brother said officials were concerned that such a move would embolden other towns protesting paroled offenders. Parole officials would not comment.

So Shasta Lake’s battle of wills continues: For now, Perkins is staying put, knowing Coulter and others are watching. Says Coulter: “If he decides to leave, we’ll help him pack his bags.”

Perkins’ sister-in-law just wants people to leave them alone: “What if it was your brother and you could see how much he’d changed? You’d do just what we’re doing.”

The brother sometimes regrets bringing Perkins to town. But he’s even angrier over how the town has handled things.

Neighbors have offered to buy the family’s house to get rid of Perkins. Sometimes he thinks he will take them up on it, just to teach them a lesson.

“I may sell, after all,” he says, “to a child molester.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.