When talk wasn’t cheap

- Share via

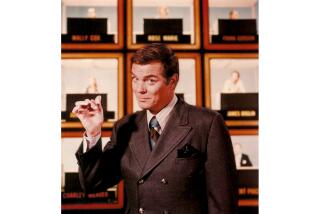

IN THE DAYS before preschool academies were all but mandatory for kids under 5, I stayed home and got my early education from Mike Douglas. His TV talk show was one of my mother’s favorite programs, and because I looked up to my mother, it became one of my favorites too.

Yet I quickly developed my own fascination with Douglas, who died last week. Maybe it was the stark set -- a couple of chairs and little else -- or maybe it was the sound of people talking about ideas and events rather than telling stories. Whatever it was, to my 4-year-old mind it was all terribly adult, like my mother’s morning coffee.

I found adult rituals sobering but compelling, especially the conversations; whenever family or friends visited and gathered in the kitchen or living room to talk, I kept quiet and listened surreptitiously from a chosen corner. Though I understood little of what was said, I knew that the grown-ups were talking about the wider world and trying to figure it out for my benefit.

In that way, I thought of Douglas and his guests as extended family. Visitors of all stripes came daily to Mike’s house to sit down and figure out stuff too. Often it sounded to me like they found some answers, or at least a point of agreement. It was reassuring. Kindergarten would be a cinch.

It was -- relatively. The grown-up world I live in now is another matter. Thanks in part to the proliferation and polarization of talk shows in the last 20 years or so -- the generation after Douglas and his big-tent gentility went off the air -- public conversations have become scary monsters indeed. Politics have hardened into extremes that the volatile ‘60s couldn’t have imagined; banter has given way to blood sport that is accepted as the only way to punch through the background noise of a million media outlets, plus iPods and other sophisticated tune-out gadgetry.

Like other forms of entertainment, the programming of commercial talk shows today has moved beyond niche to hermetic. The idea of a host booking guests as varied as Jerry Rubin, Malcolm X and Richard Nixon -- and treating them all with a certain deference, as Douglas did -- is unheard of. Equally amazing is to consider that Douglas was a moderate; though he didn’t always share his guests’ views, he nonetheless insisted on everybody having his or her say.

What he did, in other words, was more important than who he was. That was probably an easy dictate for an old-school, self-effacing guy such as Douglas to follow. But when John Lennon co-hosted with Douglas in 1972, he abided by the same rule.

And now? Oprah Winfrey is sincere enough, but her viewership is a cult of personality, not of people or issues. It’s hard to think of Oprah talking to a figure as controversial now as was Angela Davis when Douglas chatted her up in the ‘60s. (He later said he was the only interviewer who ever made Davis smile.)

Like her contemporaries, Oprah chooses her guests and issues to suit her show, rather than allowing guests and issues to be the show. She prefers uplift and empowerment, which is more palatable than name-calling, the hallmark of Bill O’Reilly or Howard Stern. But spin is spin, and in her own way Oprah gets as tiresome as those guys. Ultimately, these shows fail to convey the fullness of the conversation, the sense that America is one place -- or one host -- with many voices at equal volume.

That doesn’t mean everybody’s right. But to have everybody engaged and feeling a stake in the outcome of the discussion is priceless. Engagement is nothing less than national security: I felt that as a preschooler, watching Mike Douglas on TV, and I feel it now.

Many would argue that Douglas and his ilk had their time. The age of irony, they would say, fueled by information that moves at the speed of light, demands a different approach. Earnestness has a short shelf life.

Not so fast. There’s plenty of irony that we miss every day. We in the post-hip generation are in many ways as square as Douglas, who was the epitome of square. The difference between then and now, between him and us, is that he knew he was square. Whether we know it or not, Mike Douglas lives.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.