Remembering when they ruled -- and transformed

- Share via

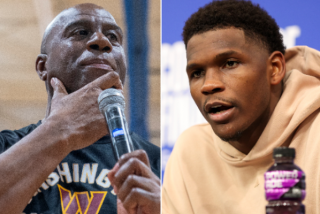

In the spring of 1979, Earvin “Magic” Johnson and his Michigan State team faced off against Larry Bird and his undefeated Indiana State squad to decide the collegiate basketball championship. Johnson and the Spartans prevailed in a game that introduced much of the nation to two sublime players and, not so incidentally, paved the way for the multibillion-dollar television contract that March Madness now commands.

Such is the influence of the Johnson-Bird rivalry, a nexus that continued after they entered the NBA together and rekindled a dormant, bicoastal feud. Johnson led the Lakers to five titles during L.A.’s “Showtime” era, as Bird was reviving Boston Celtic pride with three rings. Their presence, along with the marketing prowess of commissioner David Stern and an influx of superior talent (Michael Jordan, Hakeem Olajuwon), lifted a league beset by drug scandal and abysmal TV ratings to international renown.

In “When the Game Was Ours,” veteran Boston-based sportswriter Jackie MacMullan collaborates with Johnson and Bird to tell the story of a relationship that changed from bitter enmity to respectful friendship. The premise of the book is intriguing: With the exception of Wilt Chamberlain and Bill Russell, it’s nearly impossible to find two opposing superstars in team sports whose careers became so irrevocably intertwined. (Of course, Chamberlain and Russell didn’t compete against each other in college.)

Johnson was a pass-first visionary. A 6-foot-9 point guard, he summoned magic nightly at the Fabulous Forum alongside Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, James Worthy and a pool of complementary talent. He also courted his share of controversy. In his third season, his complaints brought about the firing of head coach Paul Westhead. He preferred to socialize with owner Jerry Buss, which some teammates resented, and in 1991 announced that he had contracted HIV.

Bird was a sniper from the perimeter who intimidated opponents (and teammates) with a combination of arrogance and brilliance. His unique court awareness transformed a corps of excellent players -- Robert Parish, Kevin McHale -- into hall of famers. Until injuries curtailed his career, he had succeeded in resurrecting a fallen franchise. MacMullan, who previously co-wrote Bird’s autobiography, notes that this notoriously private man endured his father’s suicide and, to his lasting shame, severed relations with his daughter from a failed marriage.

According to MacMullan, Johnson and Bird shared an inextinguishable competitive fervor. Both remember defeat more vividly than victory; both used the other’s success as motivation. They were also savvy enough to realize that each brought out the other’s best. (During the 1992 Olympics, Johnson scolded Michael Jordan because Jordan did not have a comparable rival. “Who do you measure yourself against?” Johnson asked.) Off the court, they were nothing alike. “Magic was effusive, emotional, and engaging,” MacMullan writes. “Bird was stoic, reserved, and enigmatic. There was also one undeniable difference between the two: the color of their skin.”

Indeed, in a league dominated by African American players, Bird was often championed as the NBA’s great white hope. He rejected this label, even as others (the Detroit Pistons’ Isiah Thomas, most infamously) complained that he was overrated precisely because of his color.

Curiously, the most controversial parts of the book revolve around Thomas. Magic says that he and others campaigned to exclude Thomas, a onetime buddy, from the 1992 Olympic “Dream Team,” although Thomas deserved the honor.

Johnson also charges Thomas with raising questions about his sexual orientation after the HIV admission. (Thomas has refuted this and other accusations.)

With “When the Game Was Ours,” MacMullan has written dual authorized biographies that occasionally intersect. That’s the major flaw of the book; the story, told exclusively in the third person, rebounds from L.A. to Boston and back. By contrast, “When March Went Mad,” a book written this year by reporter Seth Davis (no relation to this author), focused on the 1979 contest between Michigan State and Indiana State. That approach brought crisp purpose to the narrative.

It’s worth recalling that Johnson’s Lakers and Bird’s Celtics clashed exactly three times in the NBA Finals. In effect, their rivalry existed as much in their psyche -- and among fans and the media -- as on the hardwood. That doesn’t diminish its importance, but capturing such an ephemeral experience is surely as difficult as registering a triple-double.

More to Read

All things Lakers, all the time.

Get all the Lakers news you need in Dan Woike's weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.