Many Black artists are ready and waiting in the wings

- Share via

This story originally ran in 1982 as part of the “Black L.A.: Looking at Diversity” series. We have preserved the original text in order to provide an accurate account of the work in print.

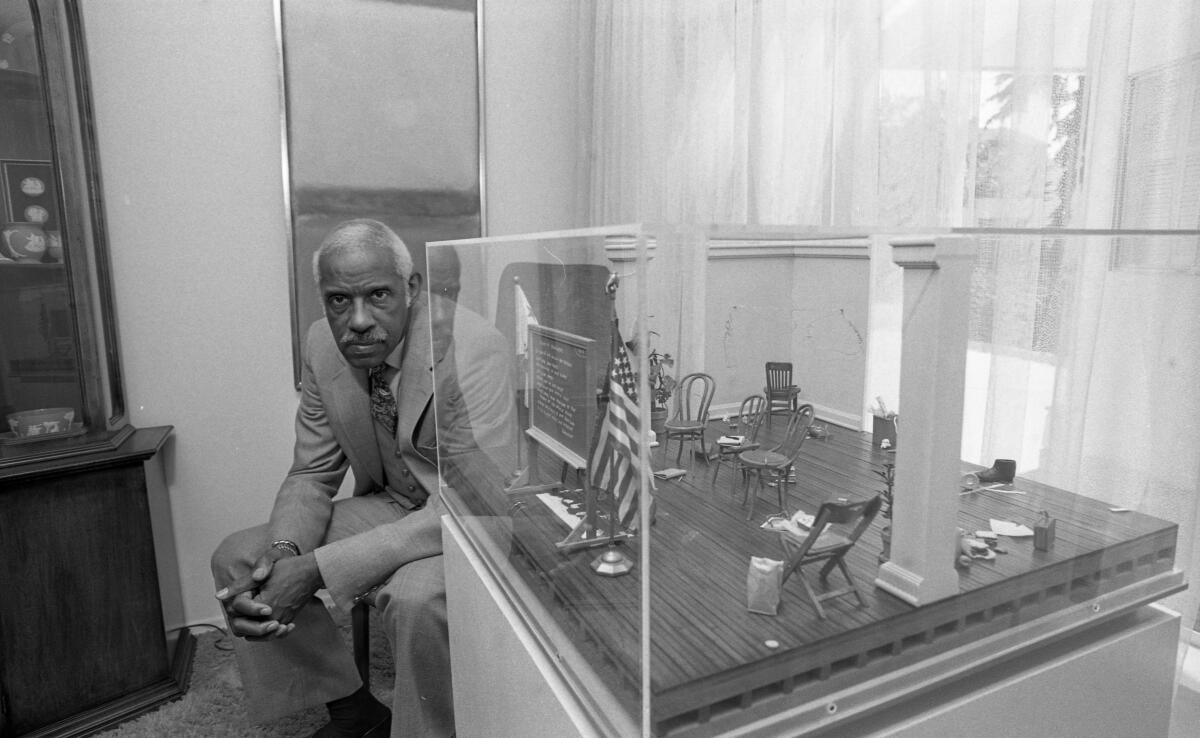

It was a tough spring for “Get Down Ben Brown” and its author, Erwin Washington.

The musical comedy opened to good reviews at the Los Angeles Cultural Center, played consistently to packed houses, and demand for tickets to future performances remained high.

But after only four weeks, the management of the publicly funded theater complex reluctantly closed down the musical because there was another production waiting to use the theater.

The play received a brief reprise there a few weeks later. This time, representative from several local theater companies saw it and a few expressed interest in mounting a major production.

So far, however, not one of the promises has come through.

“Black playwrights just get eaten up and discouraged so quickly,” Washington said. “They just don’t last here. I don’t know of a single theater in the city that is concerned about black playwrights.”

Similar sentiments are expressed in virtually every corner of Los Angeles’ black cultural arts community. For all the energy and enthusiasm fermenting among the city’s growing collection of young, talented black artists, as a group they labor under a cloud of frustration.

Black painters, sculptors and photographers complain that there are few art galleries and museums that will exhibit their work. Black dancers, actors and playwrights bemoan the paucity of legitimate theaters in their own communities and lament that few white theaters welcome their work.

Thus, lacking access to the facilities that focus public attention on their work, black artists find their ability to gain acceptance in the mainstream of cultural life painstakingly slow.

It is as though they are all dressed up, but have nowhere to go.

“There are lots of talented people, but it’s very difficult to get to know their work if they are not shown,” said Dr. Leon Banks, a black pediatrician, noted art collector and board member of the new Museum of Contemporary Art.

Compounding their problem, black artists say, is a lack of strong financial support from members of their own community. They wonder why a community that can build a lucrative financial base for popular recording artists such as Rick James and George Benson or comedian Richard Pryor cannot provide a similar base for them.

Black artists who could find no place in the American cultural mainstream thus formed a parallel network in the black community. Though tiny by comparison, it filled a void.

When the social protest of the 1960s arrived, the tumult fostered a belief among blacks that accepting “traditional” forms of cultural art meant preferring European values over African. A black aesthetic seemed the order of the day.

In response, black cultural organizations sprang to life in Los Angeles. Groups such as the Performing Arts Society of Los Angeles, the Mafundi Institute, the Watts Writers Workshop, the Black Arts Council, the Inner City Cultural Center (now known as the Los Angeles Cultural Center) and many others were active for a time.

With the exception of the Los Angeles Cultural, most of these groups went out of business during the 1970s. Black artists were left with a new awareness and pride and a burning desire for access to, and recognition in, the mainstream.

“We have a kind of resurgence of energy in the cultural arts,” said Dale Davis, who along with his brother, Alonzo, in 1967 founded the Brockman Gallery, a black art gallery.

“The energy was gone during most of the 1970s. Now I find that a lot of the things we talked about in the late 1960s are beginning to happen.”

One thing that has happened is the establishment of six galleries in Los Angeles dedicated to supporting, exhibiting and selling the works of black artists.

In the summer of 1982, The Times published a series on Southern California’s Black community called “Black L.A.: Looking at Diversity.”

There is so much black art here, however, that these six institutions are hard-pressed to handle it all.

A few of the top black visual artists in Los Angeles — Betye Saar, Frederick Eversley and William Pajaud, for example — have access to white-owned galleries, where their work is seen by wider audiences. On the whole, however, white gallery owners are slow to support and nurture young black artists in the same manner they do white artists. This makes it difficult for blacks to make it in the highly competitive art marketplace.

“Unless [a young black artist] is awfully secure, I would have him think twice about this life,” said art collector Banks. “There is very little encouragement [and] it is difficult to find anyone to run interference for you.”

For those in the theater, getting the needed exposure is not much easier.

“We’re going through a real depression,” said LeRoy McDonald, the director of the Los Angeles production of “Home,” a successful Broadway play that had a four-week run this winter at the Coronet Theater.

“There are practically no jobs [for blacks] in theater. You have ‘Sophisticated Ladies’ and a few other shows with one or two black actors, but that’s it.”

If there were more theaters in the black community, black artists say, possibly there would be more jobs for them.

There is the well-established Ebony Showcase, a 300-seat facility on Washington Boulevard with a restaurant, a multipurpose studio and other backup facilities.

Theater people complain, however, that the facility is of small benefit to the vast majority of out-of-work actors and directors because a single production there will run indefinitely — sometimes several years.

Space is also a problem at the Los Angeles Cultural Center, where Executive Director C. Bernard Jackson tries to keep a multiethnic perspective as he balances productions in the four-theater complex.

There is no lack of material from local minority playwrights, Jackson said. In fact, he gets at least 20 scripts a week. Lack of facilities, however, prevents him and others from giving a promising production, such as “Ben Brown,” the run it deserves, he said.

While many black artists see the lack of facilities to display their abilities and the lack of interest by the white cultural arts community as major obstacles, others blame their difficulties on the lack of black financial support.

“A lot of fantastic things are happening ... but no one supports black art today,” said John Outterbridge, a top black artist who runs the Watts Towers Arts Center. “Black artists have to do everything else [but art] to survive. They become administrators, they deliver mail, they do anything but art.”

County Museum of Art Trustee Robert Wilson believes the reason the museum does not own many works of art by blacks is the lack of financial support the museum receives from the black community.

Since the museum usually acquires its art through donations earmarked for specific acquisitions or through donations of artwork, a lower amount of black financial support translates into fewer numbers of black works in the museum, he said.

For generations there has not been a tradition of black financial support of major cultural institutions, partly because blacks have had to be more interested in putting food on the table or clothes on their children’s backs than in buying an original painting or holding season opera tickets.

Now, many black impresarios hope that the city’s black middle class will commit some of its wealth to make up for the loss of federal and local funding, which in the past allowed many black arts groups to survive.

That support has been slow in coming.

“People establish priorities and the average well-off black doesn’t have art as a priority,” said Dr. Richard Simms, a Harbor City dentist who has a large collection of prints, drawings and watercolors by black artists.

Consequently, black arts groups are finding themselves in an economic bind.

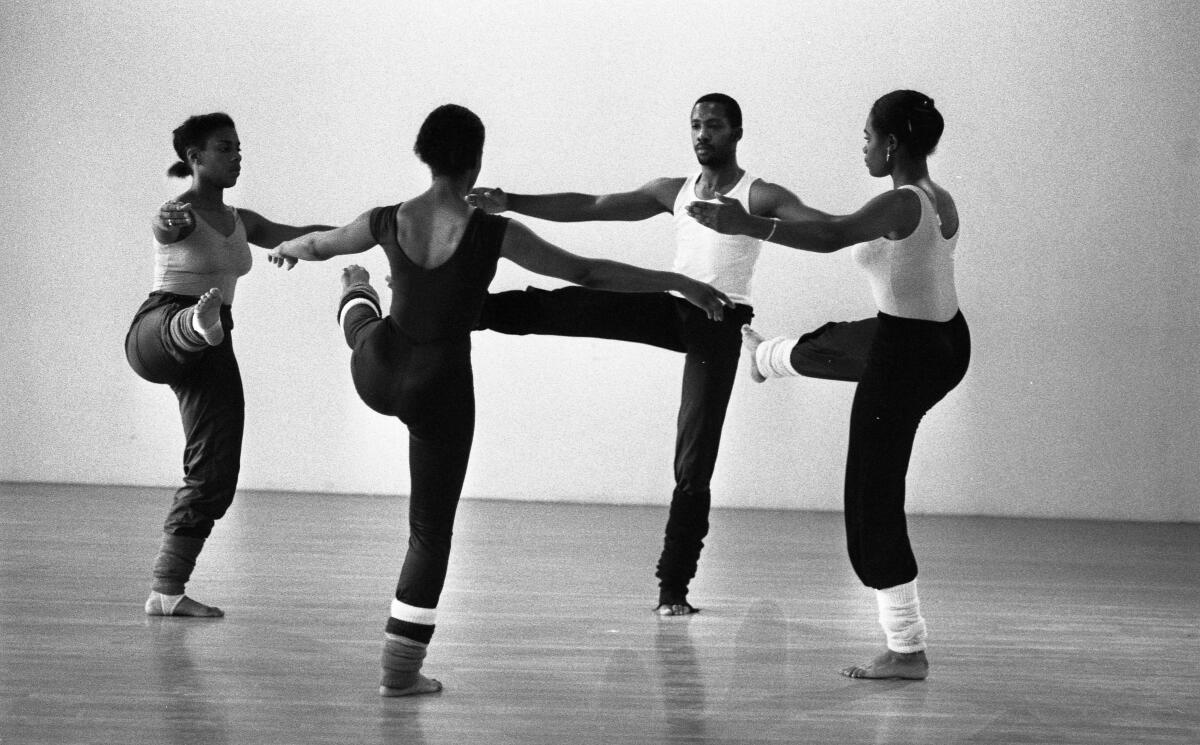

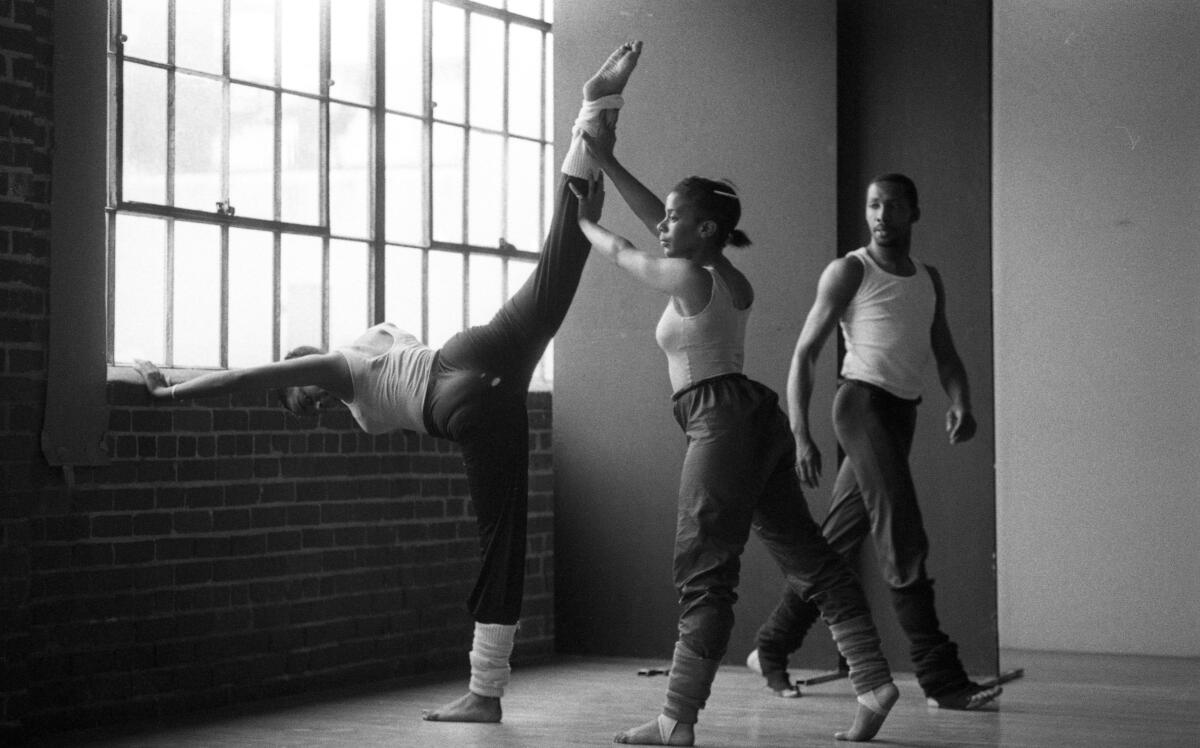

The R’Wanda Lewis Dance Company is one. When across-the-board cuts canceled its federal funding under the Comprehensive Employment Training Act (CETA), the bottom fell out of the troupe.

The company, specializing in Afro-Haitian dance, now has eight dancers, down from a high of 20 during the days of CETA. The meager backup crew consists of two drummers and two technicians.

Still, Lewis’ group is one of the busier black dance companies in the city. It receives most of its support, however, from white corporations.

“Black corporations had a chance to support [us] but didn’t,” Lewis said. “I don’t see them helping in the arts.”

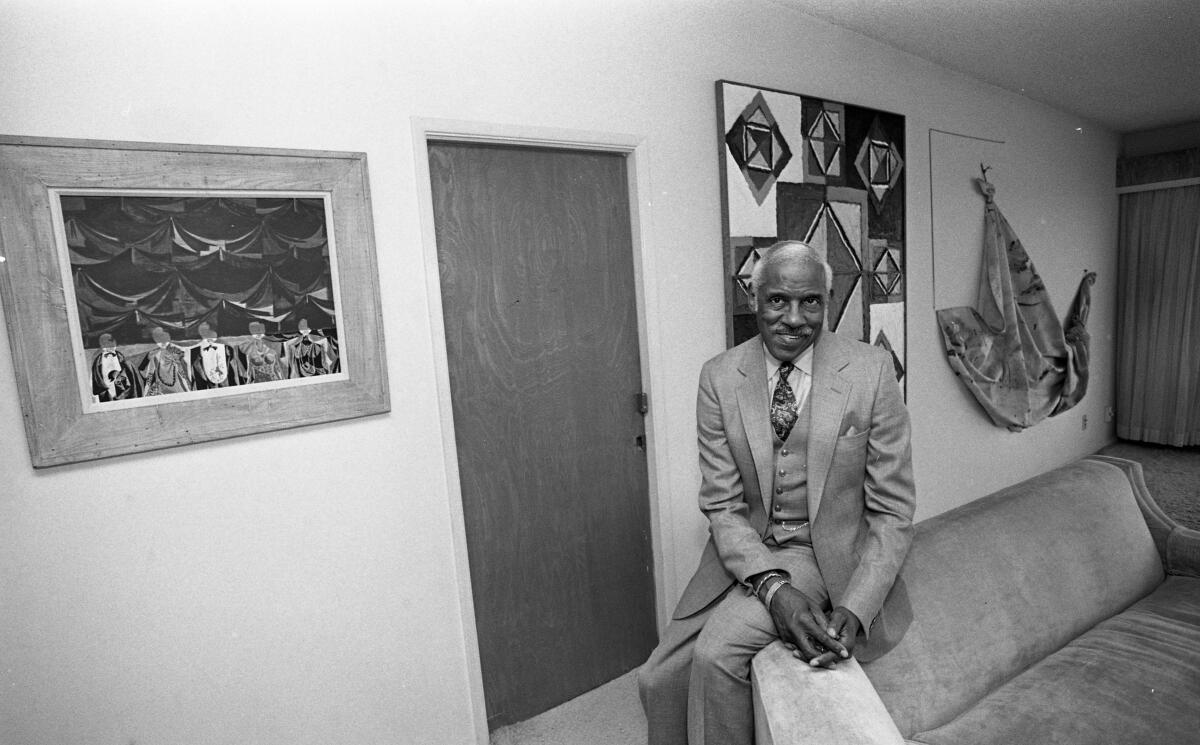

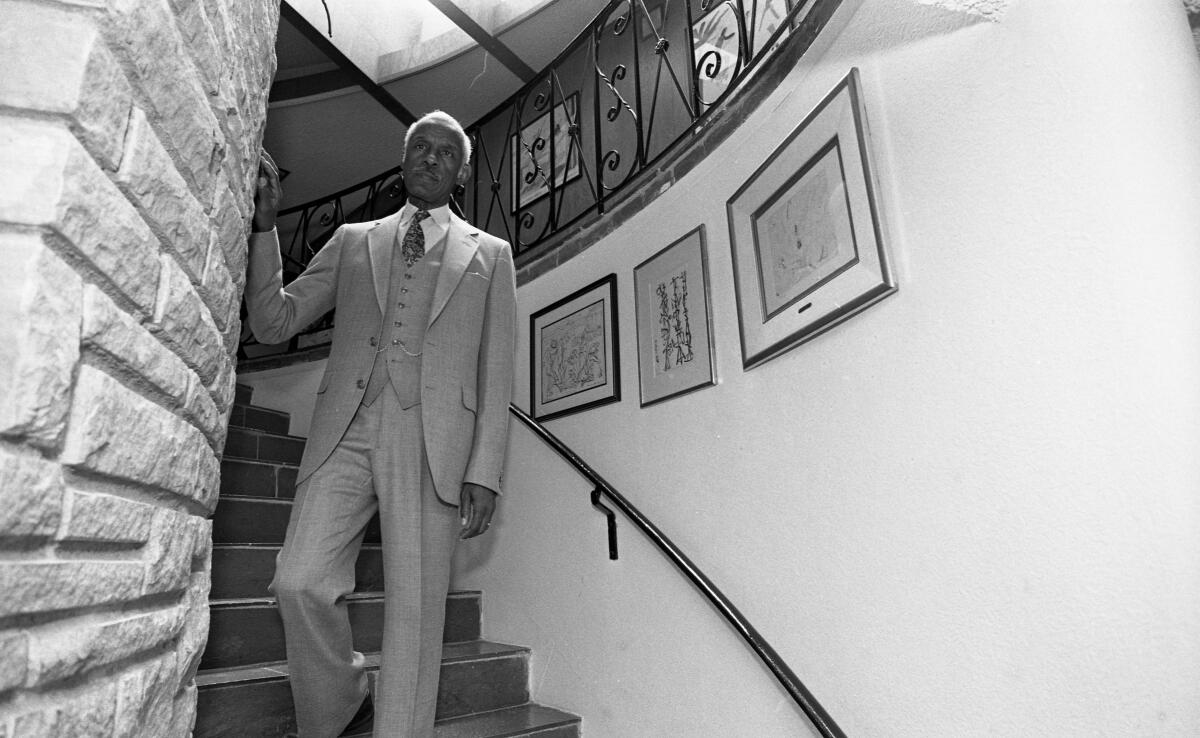

There are some notable exceptions. Los Angeles’ Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Co., the third-largest black-owned insurance company in the nation, has a collection of black art considered one of the best and largest in the West.

Motown, a diversified entertainment company and the largest black-owned business in the nation, is a major contributor to the Los Angeles Metropolitan Opera Company, a fledgling multiethnic opera company.

Black comedian Bill Cosby reportedly has one of the West Coast’s largest private collections of black art, and Muhammad Ali and Assemblywoman Maxine Waters (D-Los Angeles) are credited by the World Peace Baroque Ensemble, a black chamber quartet, for giving the group wide public exposure.

Such support, however, is sporadic and seldom comes in the form of large, continuous donations, said Jackson of the Cultural Center.

“We need to get the black community where, say, a ‘Dr. Johnson’ will vow to himself, ‘Every year, I’m going to give to the Cultural Center,’” he explained. “We haven’t yet developed that kind of awareness.

“When [the Cultural Center] started out in 1967, the audience was 80% white. Now it’s 90% nonwhite. If we could get that 90% to come up with contributions, I wouldn’t have to worry about going to the [white] board rooms for support.”

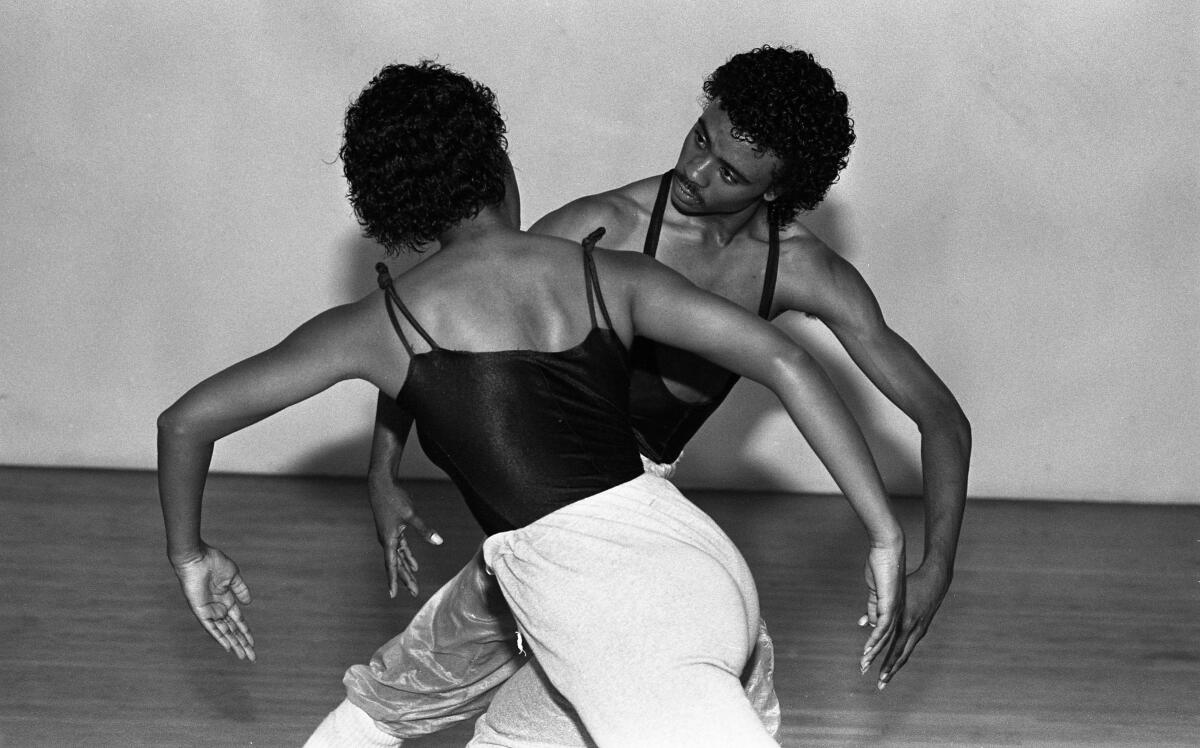

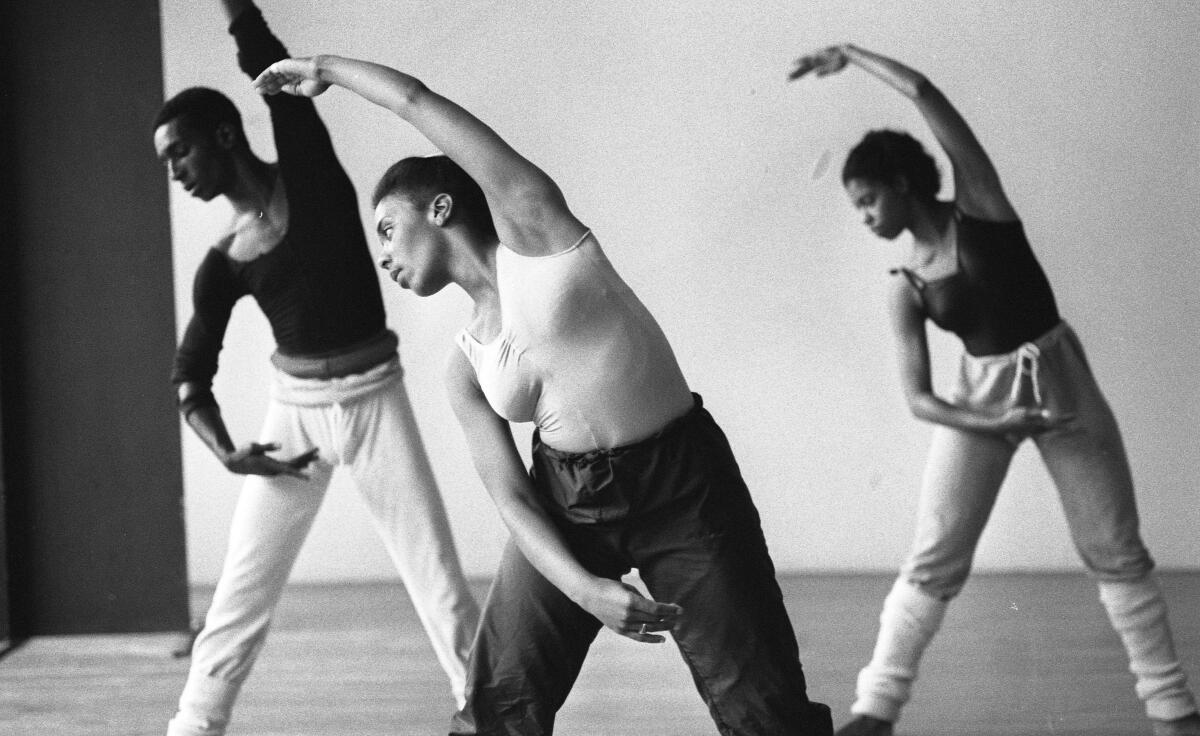

Still, for all the struggles that blacks must endure to succeed in the arts, an increasing number are entering the local scene.

Rudi Simpson, for instance, a student for 3 ½ years under George Balanchine, left New York City, considered the U.S. dance capital, to join the Los Angeles Ballet Company a year and a half ago and now appears regularly with the company.

Nearly a third of the students enrolled in the dance department at CalArts are black, said Cristyne Lawson, dean of the dance department. She said that represents a sizable increase over previous years.

And despite his disappointments, Washington, author of “Ben Brown,” is still hopeful that the future will be brighter. He is writing another play while he continues working to get his musical produced again.

Perhaps the feelings of this younger generation of black artists is best expressed by Martina Young, a choreographer and solo dancer trained in classical ballet.

“I’m very hopeful, but I have to be. The black artist must hope, and if there isn’t hope there, we have to create it.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.