From the Archives: ‘Kramer vs. Kramer’: Living anguished realities

- Share via

Perfection comes in all sizes, skyscrapers to microcircuits. At its size and weight, “Kramer vs. Kramer” is as nearly perfect a film as can be.

From its first painterly images, of the face of Meryl Streep, sad and tender and lovely in the semidarkness, the film declares its artistry, its sensitivity and its theme. She is, as we see after a long moment, looking down at the sleeping son she is about to leave.

Avery Corman’s spare and intimate novel, about a father’s battle to retain the custody of the child he had been raising by himself, has become a motion picture with an emotional wallop second to none this year.

It is a film that seems without compromise in its insistence on the truths of its characters and their anguish, and it is, for that reason, a story without villains. It is, instead, a film about innocent casualties, some of whose wounds go deeper and are slower to heal than others.

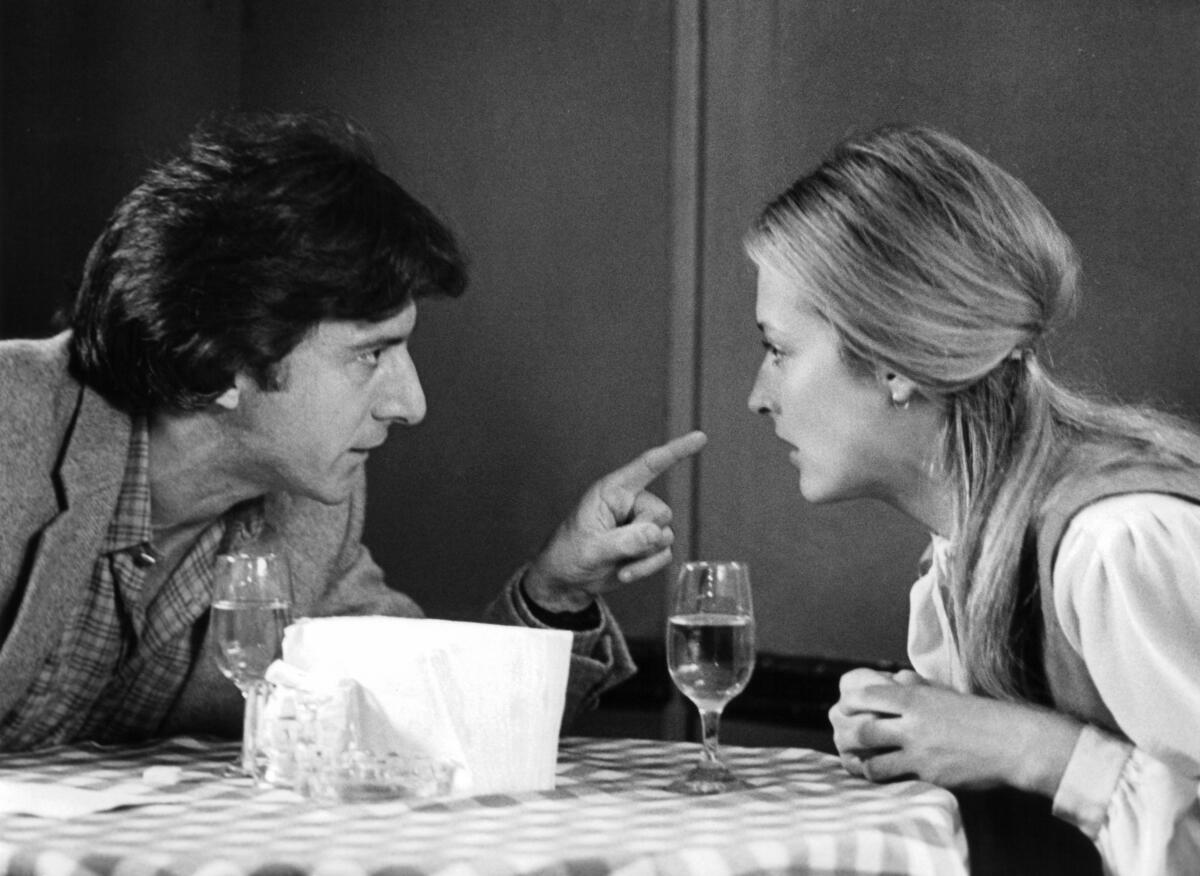

The degree to which the principal performances by Dustin Hoffman, Streep and a glorious and spontaneous child named Justin Henry (discovered as a schoolboy, not a precocious actor) seem never to be performances at all is not less than miraculous. It bespeaks the great and probing care with which Benton and his adult actors investigated the characters, so that what happens at a crucial moment arises from a whole imagined life that the audience has not seen but can itself imagine.

Hoffman has given a number of disparate and extraordinary performances in his career but none more affecting than this one, none that seems more clearly to originate in his soul as much as in his art.

Streep, eyes welling during a cruel and demeaning cross-examination during the custody trial, also gives us a portrayal that appears to be constructed of raw nerves and remembered pain. Her characterization is vital, because if she is not fully comprehended she becomes simply a selfish woman whose change of heart — suing to get her son back — is as wicked as the original abandonment. She is instead the essence of a modern dilemma, to be understood rather than scorned, and she is in her tremulous and wrenching way magnificent.

Benton’s tact and delicacy reveal themselves as well in his handling of young Justin. In this, Hoffman evidently functioned as a part-time father, good buddy and coach. If there were credits, as in sports, for assists, Hoffman would rate a large one. In petulance (“All the other mothers got here on time,” he snarls at Hoffman), in rage, tears and customary boyishness, Justin is splendidly and blessedly a small boy, never a winsome kid actor.

The movie starts at crisis point. The mother takes off for California, half-pushed by her husband’s fixation on his own career in an ad agency, more than half-pulled by her distraught feeling that there has to be fresh meaning and a point in her life. Hoffman is astonished, briefly angry and then genuinely bereft when she cuts out, leaving him with Justin.

Emotionally charged as it is, “Kramer vs. Kramer” also is charmingly funny in small details (the unflushed toilet) and large scenes, as when Hoffman tries to make French toast for his dubious son on their first hassled morning alone. He might be a figure out of a sitcom, except that the undertone of seriousness and uncertainty is as loud as our laughter.

The film is also very suspenseful, with as many surprises as a detective story, except that the shocks (which continue to the end) are on analysis logical and coherent. Its ending could go any of three ways with equal logic and equal emotional effect. The characters have been created with such roundness and depth that the audience, like the embattled child, would be prepared. But only one is right.

Benton, who co-authored “Bonnie and Clyde” and more recently wrote and directed “The Late Show,” kept faith with the novel in its spare intensity (there’s not a frame wasted or misused) and its sharp, true insights about a wounding dilemma in contemporary society. The roles of men and women are seen to be evolving, slowly, painfully, but probably at last positively.

Corman and Benton see the society — or a broad middle-class wedge of the society — as it is, with its pressures and its perils. Jane Alexander, in another of the film’s careful and deep-running performances, is like Hoffman a single parent, raising two tots in the same apartment building and wishing her husband had loved her enough to let her take him back after his wanderings.

Her role is marginally more a device than the others. She is there to provide a sort of matching viewpoint. But Alexander goes a long way toward making the woman an identifiable individual, not just a sympathetic type and a convenience.

She and Hoffman grow to be good and comprehending friends. They stop short of becoming lovers — too needful of each other’s steadying presence to risk losing it, one gathers — and the restraint measures the story’s accurate care.

There is another woman in his life, a bright, cool co-worker (JoBeth Williams) who has a marvelously embarrassing midnight encounter with cool young Billy. The casualness of Hoffman’s encounter with the woman, who actually has initiated it, also measures the story’s perceptions of the way things sometimes work now.

In other lesser roles. George Coe is excellent as Hoffman’s boss, whose sympathy goes neither far nor deep and entails no risk. Howard Duff is Hoffman’s lawyer, tough-minded and pragmatic but more genuinely sympathetic.

The photography, the natural, supportive photography, beautiful in the way it catches and reinforces the moods, is by Nestor Almendros of “Days of Heaven” and Truffaut’s recent “The Green Room.”

There is relatively little music, fragments of Henry Purcell and Antonio Vivaldi, but its classical, thoughtful, economical sound is, like everything else about “Kramer vs. Kramer,” breathtakingly right, with the kind of inevitability of choice that all fine art finally has.

In a rush in these last days of 1979 it has begun to look like a vintage year for films. In the immense pleasure it offers — the chance to care, the chance to appreciate, the chance to share both pain and joy — “Kramer vs. Kramer” is for me at the top of the list, the most satisfying of them all.

It appears to be an Oscar contender in virtually every category except, possibly, Best Song (there isn’t any song).

Rated PG. “Kramer vs. Kramer” opens Wednesday at selected theaters.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.