‘The Crusades of Cesar Chavez’ is a frank look at an imperfect leader

- Share via

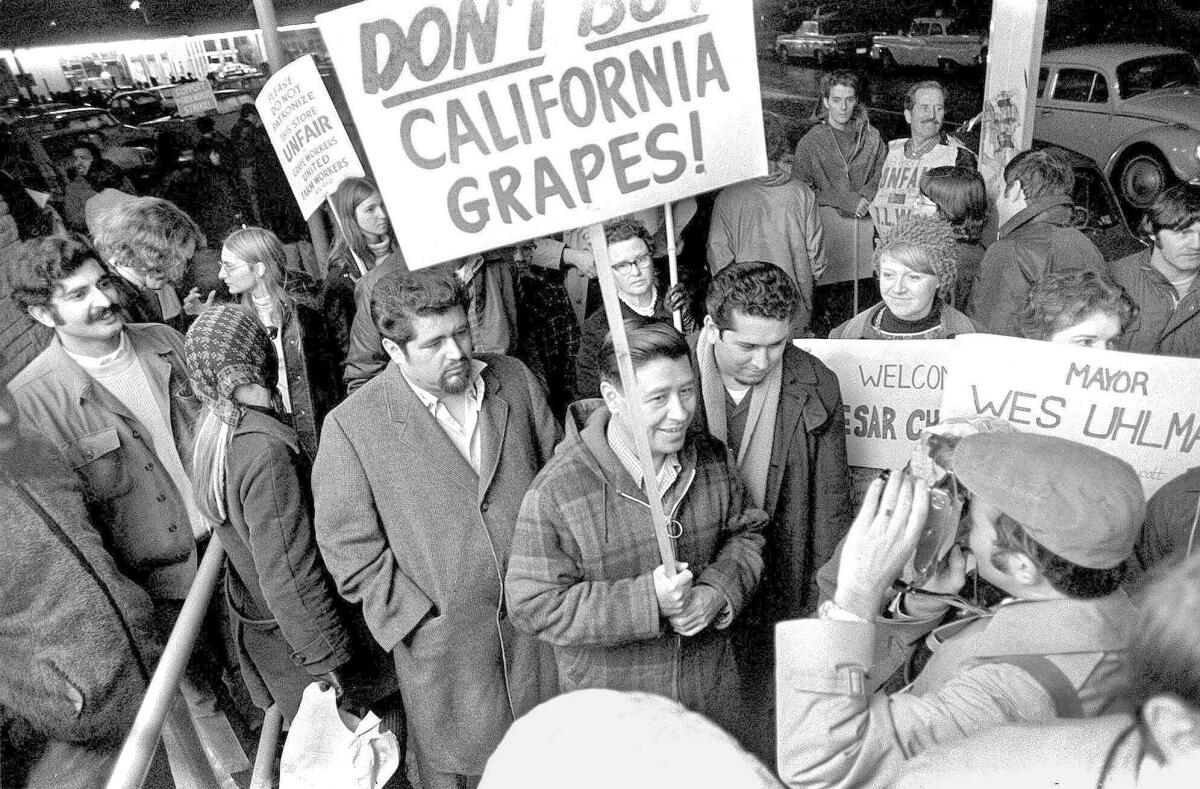

Those intent on hero worship will detest Miriam Pawel’s honest, exhaustively researched biography of Cesar Chavez, the charismatic leader and founder of the United Farm Workers who famously led strikes and boycotts to improve the lot of grape pickers in the 1960s. “The Crusades of Cesar Chavez” is a biography for readers who find real human beings more compelling than icons and history more relevant than fantasy.

Chavez’s accomplishments, extensively detailed by Pawel, a former Los Angeles Times writer and editor who also wrote “The Union of their Dreams,” a well-received book on the UFW, are stunning. He started a movement by organizing some of the nation’s poorest workers and confronting some of the richest and most powerful bosses in California. He could inspire people to give up everything else in their lives to fight for social change. In a country generally sympathetic to capitalists, Chavez made conditions in the fields a matter of nationwide outrage.

As the farmworker movement grew, it became a serious political force, feared by growers and cultivated by politicians. Chavez showed thousands, perhaps millions, that they could stand up to injustice. Pawel interviews Consuelo Nuno, who went on strike from a Delano vineyard in 1965. Forty years later, she recalls of Chavez and his organization, “They taught us how to defend ourselves.”

Pawel muses, “Chavez’s lessons about dignity outlived his union … his slogan ‘Si se Puede’ turned into a universal rallying cry.”

Yet Pawel does not shy away from the more disturbing sides of Chavez and the UFW. Chavez railed against illegal immigration, encouraging deportations — even though in parts of California most farm workers were undocumented, and many were willing to organize and become part of the UFW.

Cesar’s cousin, Manuel Chavez, working for Chavez and the UFW, hired thugs to beat up migrants at the border in Arizona and bribed local police to let the vigilantes do their work, a project, as Pawel notes, decidedly at odds with Cesar’s “steadfast commitment to nonviolence.”

Chavez was paranoid and dictatorial, tolerating no dissent even from his own organization’s most committed activists. At one point, in a board meeting, he profanely threatens, “I got to be the … king, or I’ll leave.” Pawel details many painful “purgings,” in which longtime Chavez associates and even close friends were publicly humiliated, accused of conspiring against him, and driven out of the organization. “Drawing inspiration from Mao’s Cultural Revolution,” Pawel writes, Chavez used ‘the community’ to do the dirty work.”

A man of his time, in the 1970s, Chavez followed in the footsteps of other cult leaders, adopting brutal encounter-group tactics to get members of the organization to trash and shame one another. After a while, Pawel’s book begins to read as a catalog of heartbreaking departures. Even Cesar’s brother, Richard Chavez, tells him, “I’m afraid of you … Everybody’s afraid.” But he says he is afraid to say so “because I might be one of the conspirators.”

The UFW’s healthcare plan was poorly administered, as were its contracts. When workers and staff complained about these problems or suggested remedies, Chavez shut them down. He did not cultivate — and indeed, often actively undermined — leadership from the farmworkers themselves.

Worst of all, when Chavez (understandably) got tired of organizing workers, he did not step aside and let new leadership take over the organization. Rather, he turned the UFW into something other than a union: part cultish commune, part entrepreneurial fundraising machine. In its latter years, the UFW hardly organized anyone: By 1984, the group had only one contract in the grape vineyards it had made so famous.

Chavez was constantly praying and fasting, and talking about the importance of sacrificing for the cause. As it often does in American social movements — from abolition to civil rights and beyond — such rhetoric resonated powerfully with people. But basing a movement on sacrifice had its limits. It enabled his cult of personality, since few could beat him in a sacrifice contest. But it also fueled Chavez’s obstinacy on points that led to the disintegration of his organization: the impractical insistence that staff should be volunteers rather than be paid. (“Giving up a paycheck, he argued, was a liberating experience.”) Even worse, he was outright contemptuous of the “materialistic” aspirations of the workers he represented, who did not want to be poor like Jesus. Like most people, they wanted to be middle class, with cars and big TV sets.

But as labor writer (and former UFW staffer) Michael Yates has suggested, the most important question should be: Is life for farmworkers in California any better today than it was before Cesar Chavez and the UFW came along? The answer to that, sadly, is no. As Chavez himself acknowledged, during the waning years of the UFW’s power, farmworkers’ children were 25% more likely than other American kids to die at birth. Their parents’ life expectancy was two-thirds that of the rest of the population. Laws protecting their union organizing rights were not enforced. Some drank water from irrigation pipes and lived under trees.

Despite these gaping failures, Cesar Chavez was — and is — revered as an icon. His birthday, March 31, is celebrated as a state holiday in California, Colorado and Texas. Murals depicting him looking saintly decorate our cities. A major Hollywood movie coming out this month hails him as an “American hero.”

Given the godlike status Chavez retains so long after death, this book will probably be viciously attacked. But another hagiography of Chavez — there have already been plenty — would have added nothing to our understanding of him. Perhaps by looking frankly at our social movements and their leaders, we can learn how to do better.

Featherstone is the author of “Selling Women Short: The Landmark Battle for Workers’ Rights at Wal-Mart.”

The Crusades of Cesar Chavez

A biography

Miriam Pawel

Bloomsbury: 560 pp., $35

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.