Finding Alice Munro

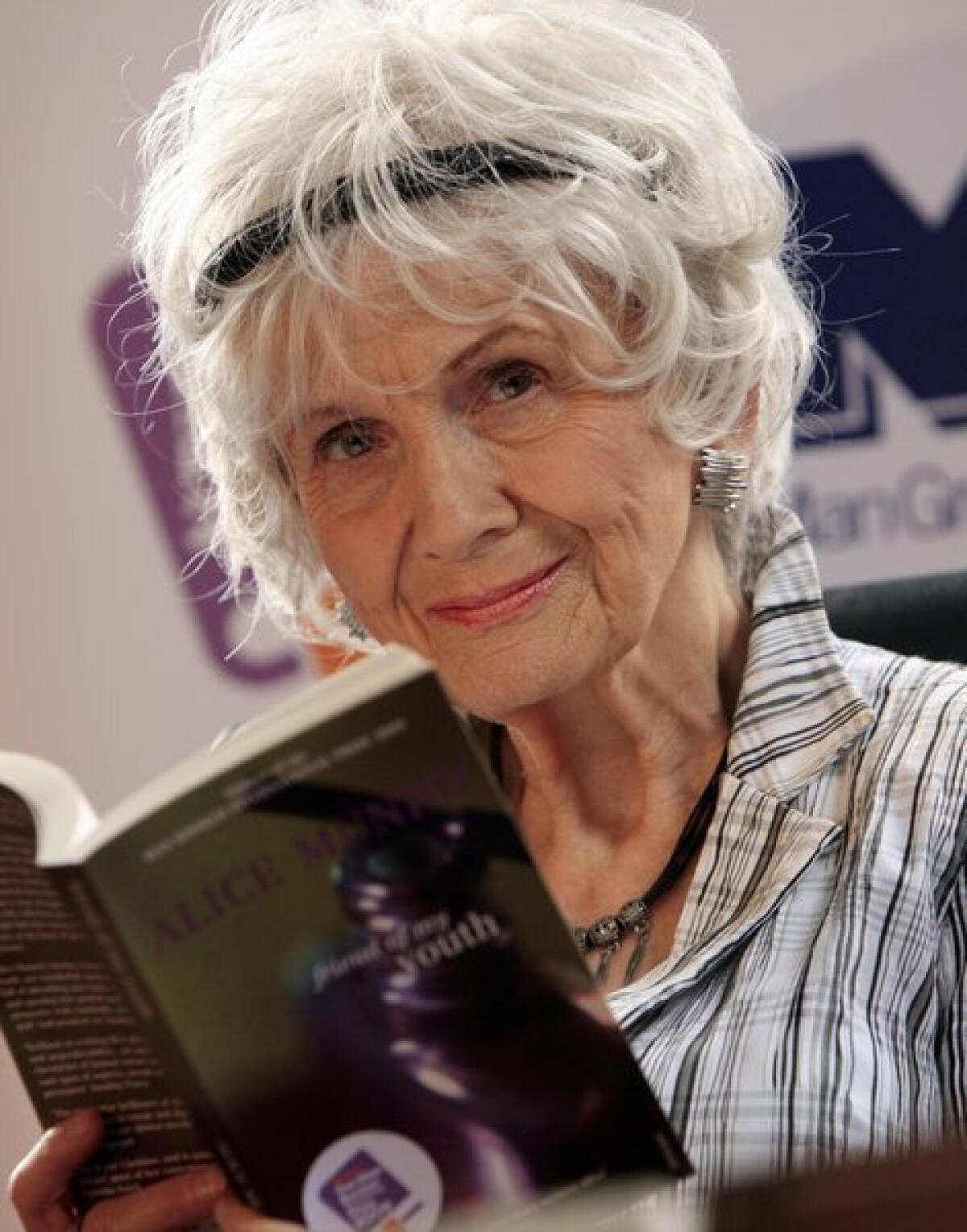

2013 Nobel literature laureate Alice Munro, photographed in Dublin, Ireland, in 2009.

- Share via

Alice Munro may not, as Carolyn Kellogg reported Sunday, be going to Stockholm in December to pick up her Nobel Prize in literature (“Her health is simply not good enough,” Swedish Academy permanent secretary Peter Englund explained. “All involved, including Mrs. Munro herself, regret this”). But she remains available in other ways.

In the wake of the Nobel announcement, the New Yorker, where she has published many stories over the past three and a half decades, allowed free access to a dozen of her pieces on its website; this week, the magazine reprints her story “The Bear Came Over the Mountain,” which first appeared in December 1999.

It’s a fitting celebration in a sense since part of “The Bear Came Over the Mountain” (which was adapted by Sarah Polley into the 2006 film “Away From Her”) deals with an aging woman and her frailty. As always with Munro, however, the story unfolds through a powerful combination of toughness and grace.

“The Bear Came Over the Mountain” revolves around Fiona and Grant, a couple whose life begins to unravel beneath the weight of dementia.

“Over a year ago,” Munro writes, “Grant had started noticing so many little yellow notes stuck up all over the house. … Fiona had always written things down — the title of a book she’d heard mentioned on the radio or the jobs she wanted to make sure she got done that day. … The new notes were different. Stuck onto the kitchen drawers — Cutlery, Dish-towels, Knives. Couldn’t she just open the drawers and see what was in side?”

Here we see the method of Munro’s artistry: to build from the smallest and most mundane details the drama of a life. Fiona ha always been a bit scattered, but she is feisty, up to the challenges of her living; when a policeman finds her wandering and asks her the name of Canada’s prime minister, she replies, “If you don’t know that, young man, you really shouldn’t be in such a responsible job.”

And yet, there’s no doubt that Fiona is fading, and once she is admitted to a residential center named Meadowlake, she declines in expected and unexpected ways. She forgets Grant, except as someone who comes to visit, and she falls into an infatuation with a man named Aubrey, who, she is convinced, she knew one summer many years before.

Whether this is true or not (it isn’t) is beside the point — Munro means to excavate Fiona’s desire. The fact that she’s infirm, even disconnected from herself, doesn’t mean that she is no longer human, and it is this that elevates “The Bear Came Over the Mountain” from the realm of the ordinary and into the profound.

As the story progresses, there are sacrifices, accommodations; Grant learns that the definition of what he can live with is a fluid one at best. I don’t want to tell too much, but the way Munro reveals him — complex, betrayed and betraying, yet ultimately picked clean by love — is one of the wonders of the narrative.

What “The Bear Came Over the Mountain” has to tell us, after all, is that life is about endurance, that the best we can hope for is to persevere. That there is dignity and (yes) even grandeur in this is the point, if there is a point; in any case, it’s all we’ve got.

“You could have just driven away,” Fiona says to Grant. “Just driven away without a care in the world and forsook me. Forsooken me. Forsaken.”

Munro goes on: “He kept his face against her white hair, her pink scalp, her sweetly shaped skull. … He said, ‘Not a chance.’”

ALSO:

Alice Munro wins 2013 Nobel Prize in literature

Alice Munro, Nobel winner and a writer’s peerless teacher

Alice Munro’s quiet, precise works lead to Nobel Prize in literature

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.