Karen Finley, Banned Books Week and the responsibilities of art

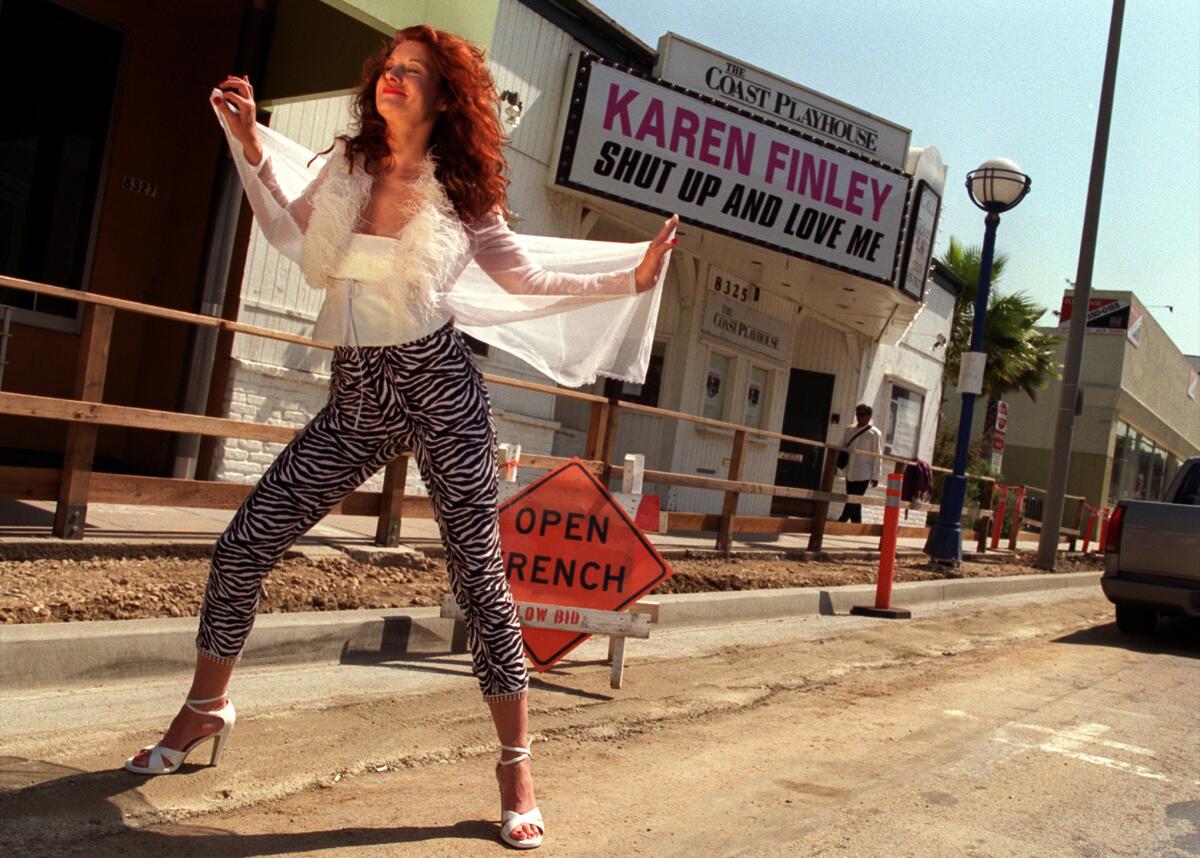

Karen Finley, photographed in 2000 in West Hollywood.

- Share via

It’s only fitting that the 25th anniversary edition of Karen Finley’s “Shock Treatment” (City Lights: 144 pp., $15.95 paper) should come out in time for Banned Books Week, the literary holiday about which I feel most consistently ambivalent. If Banned Books Week represents, in many ways, a celebration of its own good intentions, Finley’s book – like all her work — is more complicated, contradictory.

“Shock Treatment,” after all, was first published in 1990, the same year Finley became notorious, along with fellow performance artists John Fleck, Holly Hughes and Tim Miller, for having grants from the National Endowment for the Arts overturned by Endowment chair John Frohnmayer; the group, whose work Frohnmeyer considered indecent, was known as the NEA Four.

Their grants were later reinstated, although the Supreme Court ultimately ruled against them, finding that decency standards did not necessarily contradict 1st Amendment rights.

“Shock Treatment” is a collection of vignettes and poems (which grew out of what the author calls, in a new introduction, “the performance texts that were under attack”), illustrated with Finley’s blunt black-and-white illustrations; it reflects the aesthetic and political conditions of its time.

In my favorite piece, “It’s Only Art,” she frames the terms with a simple allegory: “I went into a museum,” Finley writes, “but they had taken down all the art. Only the empty frames were left.”

Replacing the art in the frames, she imagines, are explanations of why it would have been removed:

Jasper Johns — for desecrating the flag.

Michelangelo — for being a homosexual.

Mary Cassatt — for painting nude children.

Van Gogh — for contributing to psychedelia.

Georgia O’Keefe — for painting cow skulls (the dairy industry complained).

Picasso — for urinating, apparently, on his sculptures, with the help of his children, to achieve the desired patina effect.

Edward Hopper — for repressed lust.

Jeff Koons — for offending Michael Jackson.

What Finley’s getting at, of course, is morality, which has always been at the core of her work. “That’s the role of the artist,” she told me in a 2011 interview, “to interpret — not just the aesthetics of life, but actually to represent or create meaning. To apply meaning as well as to create work.” The point is that the artist is an active agent, responding to, and in some sense seeking to influence, the times.

This is the power of “Shock Treatment,” its direct engagement; “One day, I hope to God,” she writes in “Aunt Mandy,” “Bush / Cardinal O’Connor and the Right-to-Lifers each / returns to life as an unwanted pregnant 13-year-old / girl working at McDonalds at minimum wage.”

The irony — or maybe not — is that those sentiments remain relevant; the names may have changed but the landscape not so much. We are still, a quarter of a century later, fighting the once and future culture war, in a country that is as divided, as bifurcated on these issues as it has ever been.

Take Banned Books Week, which unfolds this year in a landscape of trigger warnings, in which students refuse to read certain texts because they take offense. If “Shock Treatment” has anything to tell us, it is that offense is, as it was in 1990 (or, for that matter, 1890) part of the point.

Why do we engage with a piece of writing or a performance? Do we come to be challenged or reassured? Finley’s whole career has been predicated on the former, on the sense that art should be provocative, responsive to its times.

“In the 1970s and 1980s,” she explained when I asked her about it, “women artists were marginalized to a greater extent than they are now. So I made a conscious decision that, if the female is being objectified, then I was going to objectify myself. When I was speaking, I was speaking as a voice of all women. The events in my pieces didn’t necessarily happen to me, but as a writer, who is the I, the first person? Who does the artist represent?”

At the same time, she insists, it is not enough to say that art can save us; we must be responsible for ourselves. Or, as she puts it in “Shock Treatment”:

I wish I could relieve you of your suffering.

I wish I could relieve you of your pain.

I wish I could relieve you of your destiny.

I wish I could relieve you of your fate.

I wish I could relieve you of your illness.

I wish I could relieve you of your life

I wish I could relieve you of your death.

But it’s always

Silence at the end of the phone.

twitter: @davidulin

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.