Book Review: ‘The Secret Knowledge: On the Dismantling of American Culture’ by David Mamet

- Share via

The Secret Knowledge

On the Dismantling of American Culture

David Mamet

Sentinel: 242 pp., $27.95

David Mamet’s “The Secret Knowledge: On the Dismantling of American Culture” comes with a built-in get-out-of-jail-free card: Dispute it and you’re part of the problem, a defender of the liberal orthodoxy. Such is the case, I suppose, with any polemic, but here the author is especially adamant. “The struggle of the Left to rationalize its positions is an intolerable, Sisyphean burden. I speak as a reformed Liberal,” he declares in a statement deemed significant, or inflammatory, enough to reproduce across the bottom of the book’s cover.

I beg to differ, but what do I know? I write for the mainstream media.

Actually, the media is not Mamet’s main concern in “The Secret Knowledge,” although he does offer up his share of barbed remarks. He’s got bigger fish to fry. Among his targets: liberal education, the New Deal, Al Sharpton, global warming, “Obamacare” and the bailout of the auto industry. If such a list sounds familiar, that’s because the bulk of it is made of Fox News talking points, generalities equating liberalism with socialism and framing it as venal, lazy, anti-American — a children’s crusade with no understanding of realpolitik.

“Liberalism is a religion,” Mamet writes in a typically unsupported statement. “Its tenets cannot be proved, its capacity for waste and destruction demonstrated.” But as to what this means, he remains vague and imprecise. Throughout the book, he makes definitive statements with no basis in reality about multiculturalism, the state of the university, the ability of the free market to self-correct.

For Mamet, the fact that “[t]he young on the Westside of Los Angeles dress themselves in jeans worn, sanded, and razored to resemble something a six-month castaway might crawl ashore in” is an expression not of the idiocy of style but of “a charade of victimization, as the ethos of the Liberal West holds that these victims are the only ones of worth.” His critique of affirmative action relies on a dismissal of race — “When,” he asks, “was the last time you heard a racist remark or saw racial discrimination at school or work?” — that is so divorced from the reality of many Americans you have to wonder where he lives.

The problem with these positions isn’t that they are conservative, it’s that they’re so easy to refute. “[T]hough much has been made of the necessity of a college education,” Mamet writes, seeking to connect the rise of school shootings to what he sees as the aimlessness of liberal arts curricula, “the extended study of the Liberal Arts actually trains one for nothing. And the terrified adolescent, abandoned by society, coddled by society, may, if unbalanced, turn to rage and (a) kill; or, if merely clueless, (b) hide in college, as he does not possess the strength to grow up and leave.” Really? And here, I’ve always thought that school shootings were the responsibility of the shooter, not of the system. I guess I ought to thank him for clearing that up.

Such arguments, spurious though they may be, are just the tip of the iceberg because Mamet wants to dispatch with liberalism in its entirety. In many places, this requires a kind of historical revisionism bordering on fantasy. “The Left insisted that we abandon, in 1973, a war we had just won in Vietnam and go on home,” he writes, an interpretation I’ve never heard before. Similarly, he tells us no fewer than three times that FDR did not end the Depression but rather prolonged it, a conservative trope that derives from a 2004 UCLA study by economists Lee H. Ohanian and Harold L. Cole — one of the few interpretations of Depression-era economics to suggest that Roosevelt played anything other than a beneficial role.

In Mamet’s view, Roosevelt’s inadequacies are analogous to Barack Obama’s, primarily the bailout of Chrysler and GM. But while he hammers the president for his policies (“just as the camel is a horse put together by a committee,” he notes, “actual ‘government cars’ … put together under the supervision of a board of majority government appointees, will be neither fish nor fowl, nor sufficiently safe, efficient, attractive, affordable, durable, or fun”), his argument overlooks two key facts.

First, the government was never involved in the manufacture of automobiles. And second, the bailout, by most accounts, has been successful, with Chrysler having just repaid $7.5 billion in bailout loans. This suggests a certain selectivity of details, a tailoring of facts to fit the argument. At times, it also leads to unintended ironies, as when Mamet cites the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, the Food and Drug Administration, the Consumer Product Safety Commission (which he calls the Consumer Safety Board) and the Department of Homeland Security as evidence of top-down liberal bureaucracy, when, in fact, all of them were created under Republican presidents.

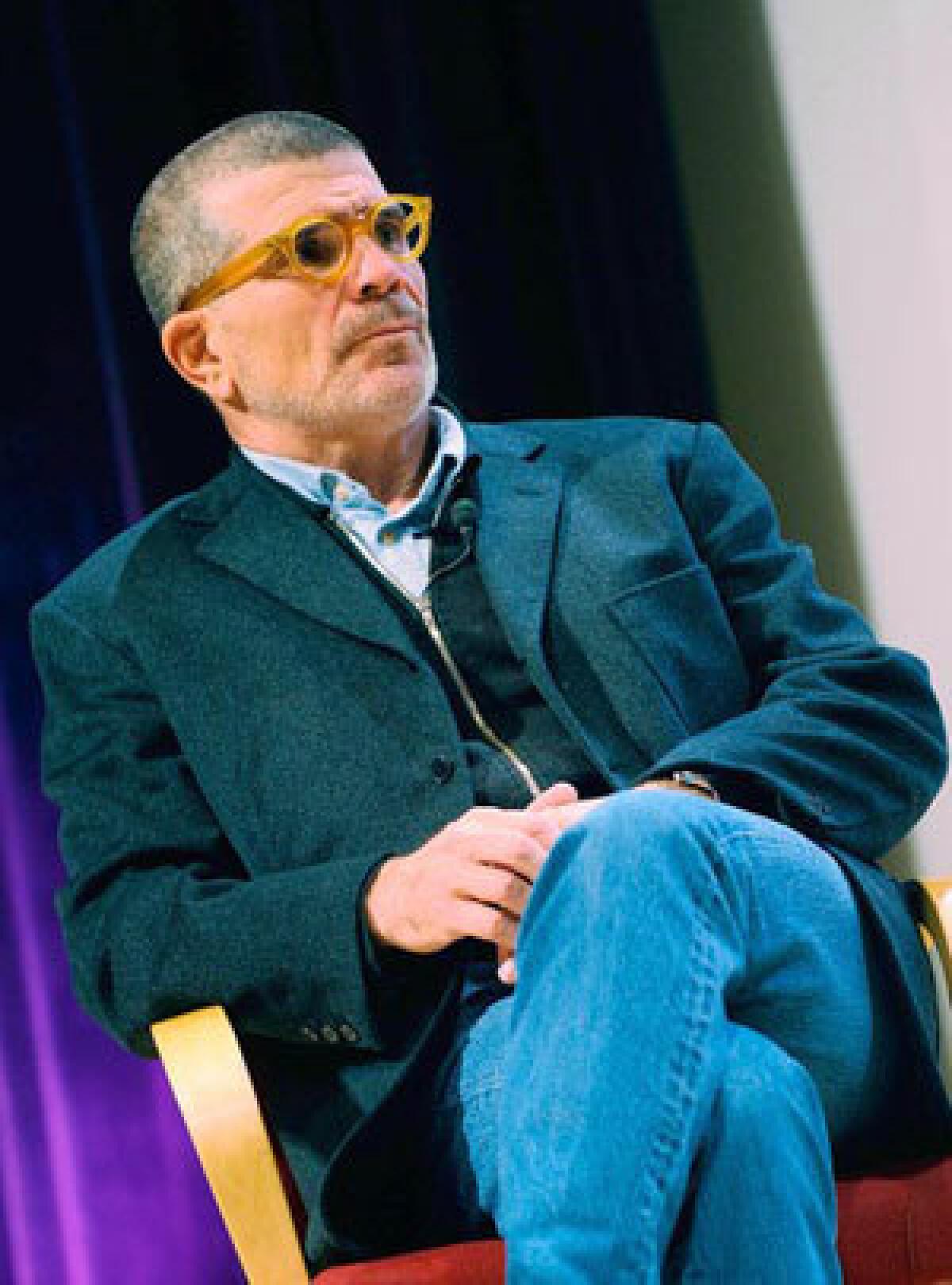

What’s most disturbing about “The Secret Knowledge” is that Mamet is a smart guy, author of one of the great plays of the last 40 years (“American Buffalo”) and winner of a 1984 Pulitzer Prize for another, “Glengarry Glen Ross.” Here, however, he continues in the shrill, strident vein that marked his 2006 book “The Wicked Son.” That work traced his return to (or perhaps more accurately, his adoption of) a form of socially conservative Judaism; “The Secret Knowledge” takes this shift into a purely political realm.

Both books lack a spirit of dialogue and debate. “The bifurcation of Humanity (as opposed to acts) into two identifiable camps, Evil and Good, is, essentially, a childish act,” Mamet writes in his new book. The idea that “one may gain merit from this division, and that this merit makes one the superior of the unenlightened, is the act of an adolescent.” It’s a valid point, but in the end, it makes for yet another irony, as such a bifurcation is the essential condition on which this book depends.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.