Gere Kavanaugh’s color avalanche brightened midcentury California design

- Share via

In a 1968 magazine profile, longtime Los Angeles designer Gere Kavanaugh gave an insight to her spirited creation of everything from fabric and furniture to shopping mall interiors and toys:

“There’s no pat solution in life — for school, marriage, family. It isn’t that easy or that dull. Stay loose — keep open! You have to learn to walk on marbles.”

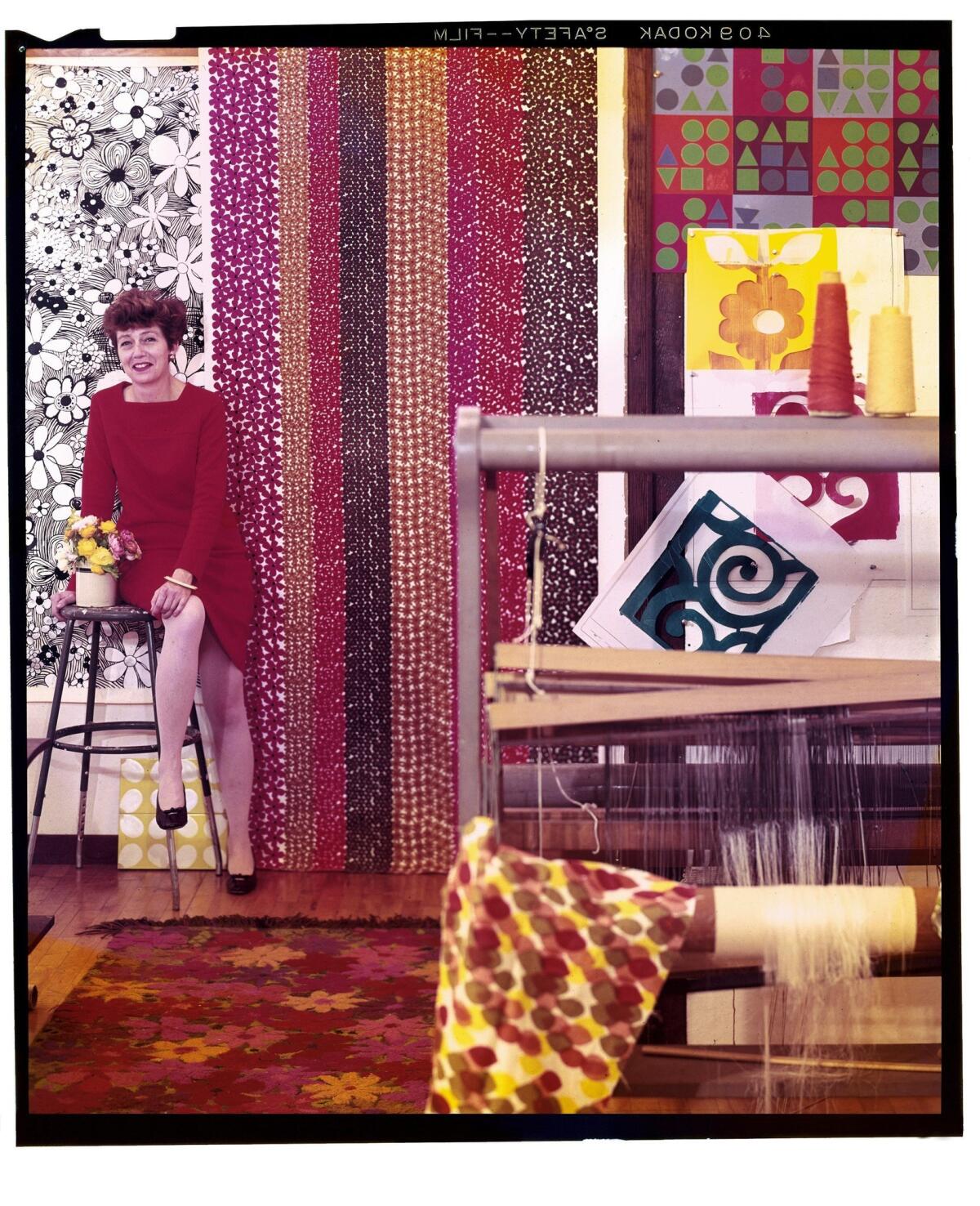

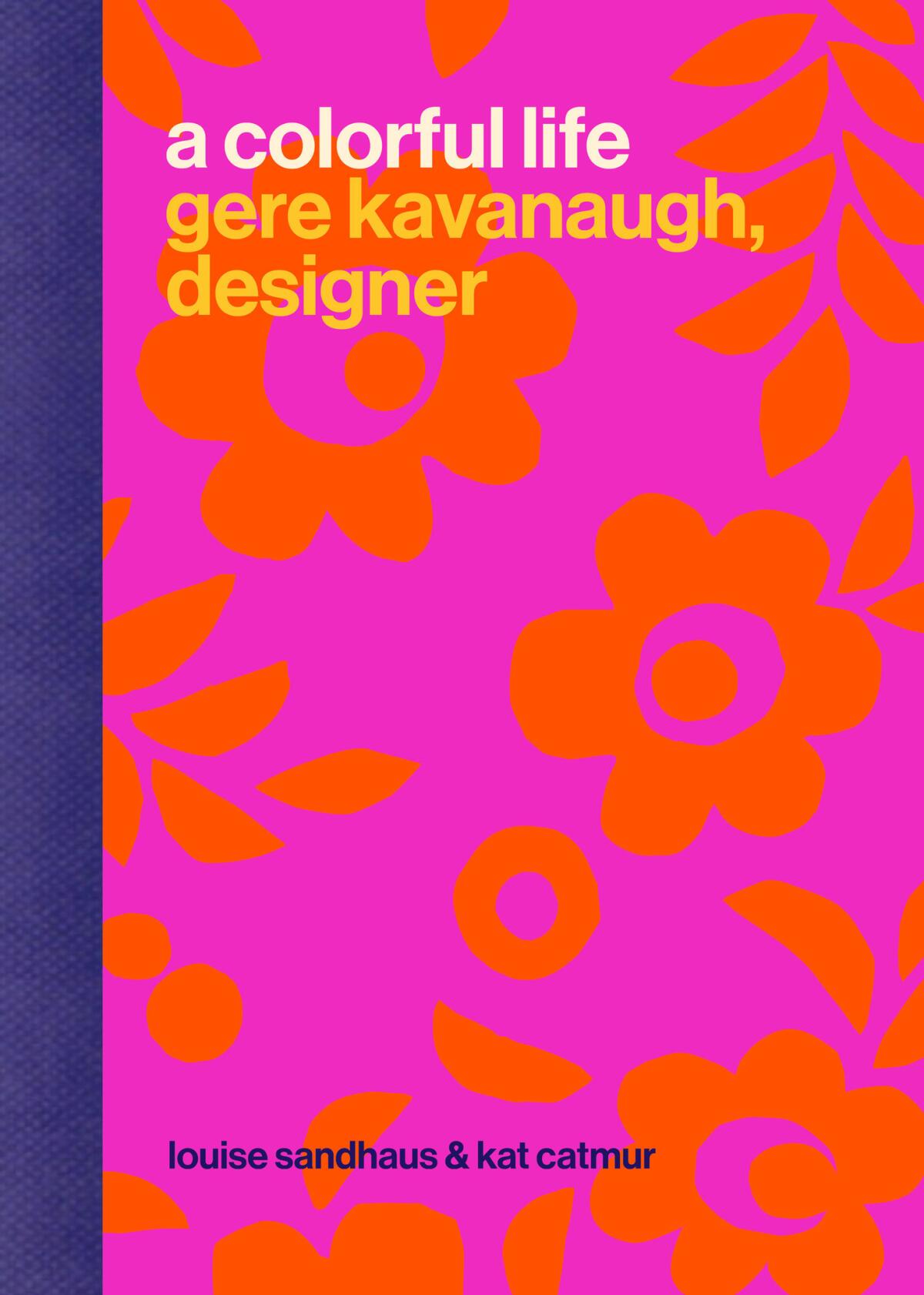

The article described her as “freewheeling,” a term frequently splashed on the omnivorous Kavanaugh and her exuberant style, which came to represent a popular version of spirited California design. “A Colorful Life: Gere Kavanaugh, Designer,” the first monograph on Kavanaugh’s life and work, tells her story through a fascinating avalanche of visual material. The book by fellow Southern California designers Louise Sandhaus and Kat Catmur surveys Kavanaugh’s seven decades of work, which reveals a dazzling wealth of intuition and talent, plus her elastic ability to distill the present moment like a true marble-walker.

“Vibrant as a rainbow,” is how the Ojai-based Sandhaus describes Kavanaugh, whom she hails as “a mighty presence in the Los Angeles design scene since 1960.” (Sandhaus would know. Besides being an heir of Kavanaugh’s contributions to the field, she is also author of the 2014 book “Earthquakes, Mudslides, Fires & Riots: California and Graphic Design, 1936-1986,” for which Catmur created flowcharts of local design lineages.)

It was here in California, Kavanaugh says, that “color really hit me.” 1960 was a good time to be stunned by the electric poppy, bougainvillea and jacaranda blooms. The decade would also usher in an embrace of acidic, fluorescent colors and patterns, which became a hallmark of Kavanaugh’s work.

Born in Memphis, Tenn., in 1929, Kavanaugh started taking weekend art classes as a child. After college she moved to Michigan for graduate school at the legendary Cranbrook Academy of Art. There she was allowed to explore and experiment widely and across disciplines — drawing, prints, books, sewing, textiles, jewelry and furniture design. She learned to avoid specialization. She graduated in 1952, becoming the third woman to earn an MFA in design at Cranbrook, and was soon hired by General Motors as one of its “Damsels of Design” to work on car interiors, kitchen appliances and its lavish modern showrooms. Her ideas were fresh and inventive: For a spring showcase of new cars she conceived of a garden party theme, filling the auditorium with blooming hyacinths and creating 30-foot-high bird cages containing 90 singing canaries. Soon she was choosing between offers at architecture firms run by Finnish architect and industrial designer Eero Saarinen in Michigan or architect Victor Gruen in Los Angeles. She took a fateful one-week trip to check out the West Coast, visiting the artist-activist nuns Sister Corita Kent and Sister Magdalen Mary, who welcomed her warmly and insisted she relocate to Los Angeles. She complied, embracing and embodying the colorful region where she still resides today.

Kavanaugh was put in charge of interiors at Victor Gruen Associates, which specialized in building department stores and shopping malls. It was still the heyday of shopping as a chic and entertaining excursion, and Kavanaugh’s designs for the color scheme, lighting, carpets and wall treatments — what she deemed “the whole everything” — display a variety of immersive environments. Some were elegant and sleek , others whimsical and full of flower power on every surface, like a Pop art garden. She also met her lifelong friend Frank Gehry at Victor Gruen Associates, and the two of them shared a studio for several years after she branched off to form an independent practice in 1964. With ultimate design freedom, Kavanaugh also commissioned remarkable work by her friends, such as sculptures by then-unknown artist Ruth Asawa for a store in San Francisco, and vibrant wall coverings by Sister Kent and her students for the Gehry-designed Magnin store in Costa Mesa.

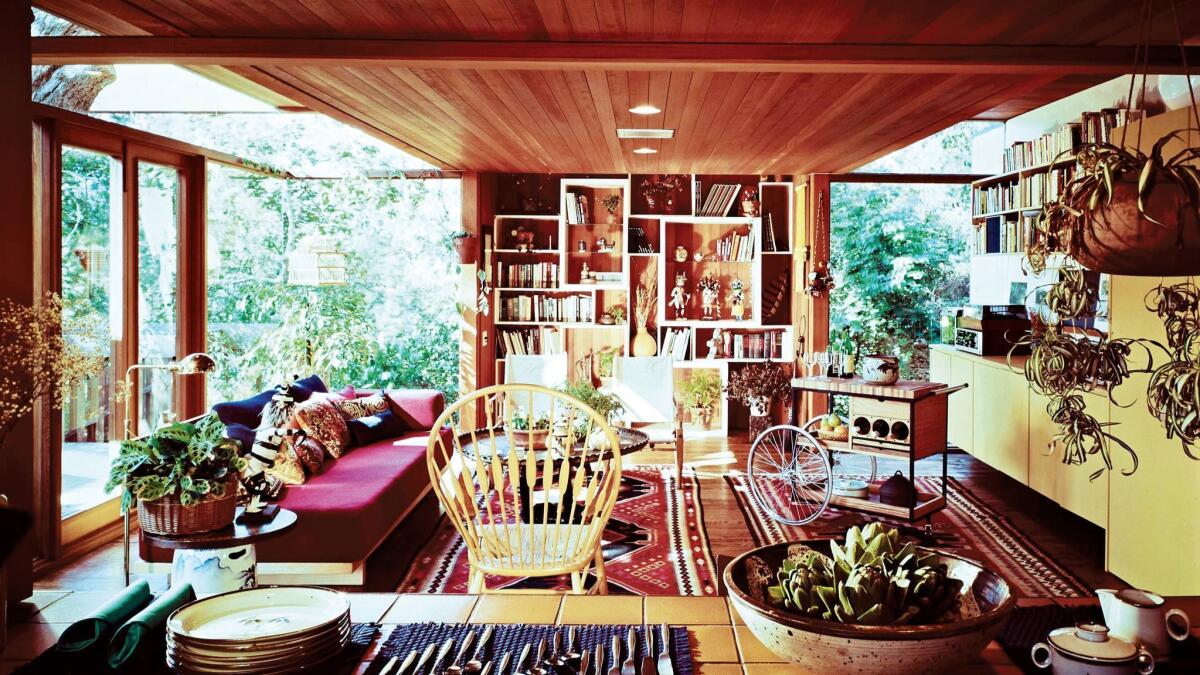

Over the years, Kavanaugh nimbly worked with an impressive span of materials and projects for a range of local and international clients. She focused on her own home too, which Sandhaus and Catmur describe as being like a museum, full of her prototypes, collected folk art, gourds clustered on the floor, chopsticks pinned across a window, a bevy of teapots and antique baskets hovering on the ceiling.

The design of Sandhaus and Catmur’s book is an homage to Kavanaugh’s style, joyfully mirroring her passion for color with deeply pigmented pages, text and full spreads of her sanguine patterns. Newspaper and magazine articles are scanned in original form, and snapshots and portraits give it a personal, scrapbook feel. The captions hold wonderful details too: Kavanaugh’s gold-orange poppy-patterned wallpaper is revealed to have been used in the movie “Rosemary’s Baby,” and a framed letter on her wall turns out to be from Buckminster Fuller, replying to her idea about toy-sized geodesic domes.

Several affectionate testimonials about Kavanaugh are included, written by collaborators and colleagues who recall her gift for both design and a life well-lived. Kavanaugh’s own joie de vivre is written on the inside covers of the book, where she’s included a long and eclectic list of thank yous against a background of sky blue. They include many people, but also many things: fairy tales, Santa Fe, New Mexico, Korean ceramics, “any alphabet,” birds and “midyear light in Los Angeles.” True to the outpouring of life in her effusive work, her list doesn’t end. Instead, the 90-year-old designer stays loose and keeps open: “I could go on and on and on.”

::

Louise Sandhaus and Kat Catmur

Princeton Architectural Press, 244 pp., $40

Kilston is a Los Angeles writer and editor, and author of “Sun Seekers: The Cure of California.”

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.