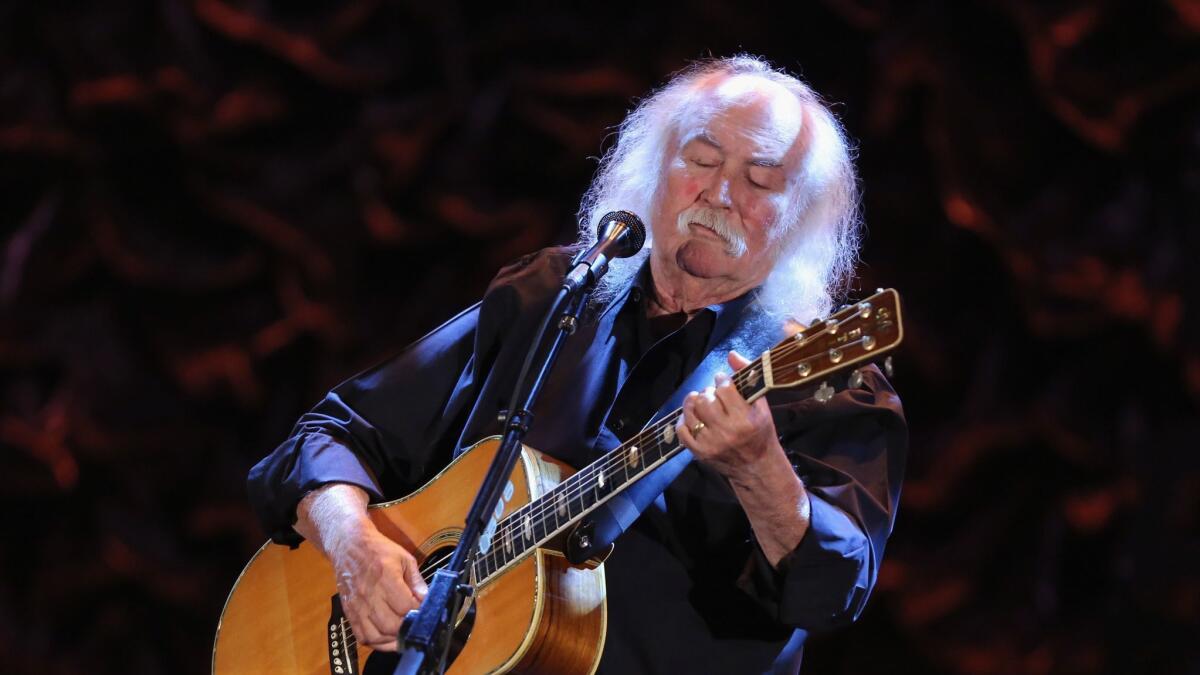

With documentaries on David Crosby and Joan Jett, music company BMG is pushing into the film business

- Share via

David Crosby was in talks with BMG for his next studio album about a year ago, when his manager told the record label they were working on an unusual project: an intimate documentary about the folk rock hero. Better yet, “Almost Famous” filmmaker Cameron Crowe was already involved.

Though not a typical Hollywood financier, BMG jumped at the chance to produce and fund the movie. Executives thought the life story of Crosby, 76 — an outspoken political activist who has enjoyed a late-career creative resurgence — would make for a compelling big-screen experience.

For the record:

7:00 a.m. April 3, 2018An earlier version of this article stated that the David Crosby documentary would be released in September. It does not have a release date.

“They declared their love and support of David and they showed that they don’t want to mess around,” Crowe, the documentary’s producer, said of BMG. “It’s like working with someone who’s got a lack of fear and a large quantity of love of music and cinema.”

The music industry — finally enjoying a comeback thanks to streaming services Spotify and Apple Music — is increasingly looking to film and TV to grow its audience, as young people turn to sites such as Netflix and Hulu for entertainment. Labels also see film as a powerful way to promote artists on their rosters.

“There’s more channels now than there ever have been,” said Zach Katz, BMG’s U.S. president of repertoire and marketing. “It’s such a robust opportunity and such a great time.”

The as-yet untitled film about the former member of the Byrds and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young is just the latest example of a larger push by BMG — owned by German media conglomerate Bertelsmann — to become a prolific producer of music-themed movies.

The company in February sold the North American rights for its Joan Jett documentary “Bad Reputation” to Magnolia Pictures for an undisclosed amount after debuting at the Sundance Film Festival. Films about the influential reggae label Trojan Records, rock band T. Rex and 1970s concert promoters are also in the works. BMG plans to make up to five film projects a year, with investments of about $2 million in each documentary.

“These are not just one-off opportunistic kind of events,” said Kathy Rivkin-Daum, director of BMG’s budding audiovisual business in Los Angeles. “We are shaping these projects and taking them to market.”

BMG is the most recent major music company to get into the business of producing films as record labels and publishers look for revenue sources beyond album sales and streaming royalties.

Universal Music Group, led by Chairman Lucian Grainge, produced “Amy,” the 2015 film about the late singer Amy Winehouse that won the best documentary Oscar. The label also produced Ron Howard’s 2016 Beatles documentary “Eight Days a Week — The Touring Years.” Warner Music Group’s Atlantic Records produced a documentary about the famous Roland TR-808 drum machine that was released in late 2016 on Apple Music.

Record labels are following the lead of major movie studios that have long mined music industry lore to make popular films such as the N.W.A biopic “Straight Outta Compton,” which was a box office hit for Universal Pictures in 2015. 20th Century Fox is preparing the Freddie Mercury biographical film “Bohemian Rhapsody” for a November theatrical release.

“These are very strategic initiatives across companies that have in many ways restructured themselves to address new business opportunities that exist today,” said Larry Miller, a music business expert at NYU-Steinhardt.

Nearly two decades after online piracy forced the closure of CD stores and record labels, music companies today have the financial wherewithal to try their hands in filmmaking. The music business is in the midst of what industry executives call a “fragile recovery.” U.S. sales of recorded music grew 16% to $8.7 billion in 2017, marking the first time since 1999 that the industry has grown materially for two consecutive years, according to the Recording Industry Assn. of America.

“There’s real money being made in this business again and there’s greater willingness to invest in projects that would’ve been off the table five years ago,” Miller said.

BMG’s Hollywood ambitions come as the company is trying to stage its own comeback. Bertelsmann exited the music industry in late 2000s, selling its music publishing business to Universal Music in 2007. The company sold its 50% stake in joint venture Sony BMG to Sony Corp. in 2008.

Bertelsmann relaunched BMG in 2008, teaming with New York private equity firm KKR in the following year to grow the business by acquiring independent record labels and publishers including Chrysalis Music and Bug Music. BMG, now wholly owned by Bertelsmann, is the world’s fourth-largest music publisher, and represents more than 2.5 million songs and recordings.

BMG’s 2017 revenue was $627 million, up 22% from the prior year. Operating profit grew about 10% to $128 million.

The company attempted to launch its foray into film as early as 2013, when it tried to buy Eagle Rock Entertainment, a London-based production company known for concert films and music documentaries. But after it was outbid by Universal Music Group, BMG was forced to go solo. Its lean film and TV operation, led by BMG Senior Vice President Justus Haerder, consists of four employees.

“Once we realized the transaction wasn’t happening, we decided to start it from scratch,” Haerder said. “It takes more time there’s no doubt. But we can shape it the way we really want to, and that’s a beautiful thing.”

Its first documentary “Bad Reputation,” solely financed by BMG, follows “Cherry Bomb” singer Jett and her all-female band the Runaways in the early punk rock scene and her later influence.

The company, which is planning to release the film this year, is betting the message of female empowerment will resonate with contemporary audiences. When BMG took the movie to Sundance, Jett performed live and was joined onstage by Kathleen Hanna of the pioneering riot girl band Bikini Kill.

“We pretty much started at the top,” Rivkin-Daum said. “It was a picture perfect experience.”

The company hopes to follow up by finding other powerful stories in the music industry. Its upcoming film “Rudeboy: The Story of Trojan Records,” chronicling the rise of reggae, ska and rocksteady in Britain from the early 1960s through the late ’70s, emphasizes themes of immigration and the intersection of Jamaican and skinhead cultures. BMG, which owns the 50-year-old label, teamed with Pulse Films, known for Beyoncé’s “Lemonade,” to produce the picture.

The Crosby film, directed by A.J. Eaton, is an especially important initiative for BMG, which released the artist’s 2017 studio album “Sky Trails.”

Crowe, who has interviewed Crosby since he was a 15-year-old rock journalist for Rolling Stone, said he wanted to make the film as personal as possible. He filmed several marathon interviews with Crosby, including one at his studio and another on the steps of hippie haven Laurel Canyon Country Store.

“The idea from the very beginning was, ‘David, you are a fascinating storyteller. Let’s make this as if you’re telling your best stories to a very close friend,’” Crowe said.

BMG is set to release Crosby’s next studio album, making the documentary a well-timed investment for the label. But Rivkin-Daum said the goal is not to make movies that are merely meant to drive record sales.

“We just seek to make great films,” she said. “We take a broader, more long-term look at our artists.”

Twitter: @rfaughnder

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.