Weinstein Co. serves up ‘The Founder’ amid smaller film slate and shift to TV

- Share via

In Weinstein Co.’s “The Founder,” opening nationwide this week, McDonald’s executive Ray Kroc (Michael Keaton) uses strong-arm tactics to wring gold from the golden arches, turning them into a ubiquitous symbol of American success. But in the process, he alienates associates and burns his share of bridges.

Can Harvey Weinstein relate? The movie boss possesses a similar kind of Midas punch. By sheer force of personality, he has transformed the numerous independent films under his banner into Oscar and box-office gold. But the luster of the Weinstein brand isn’t what it used to be as the company has dealt with a tough two years at the box office and a rapidly changing indie landscape.

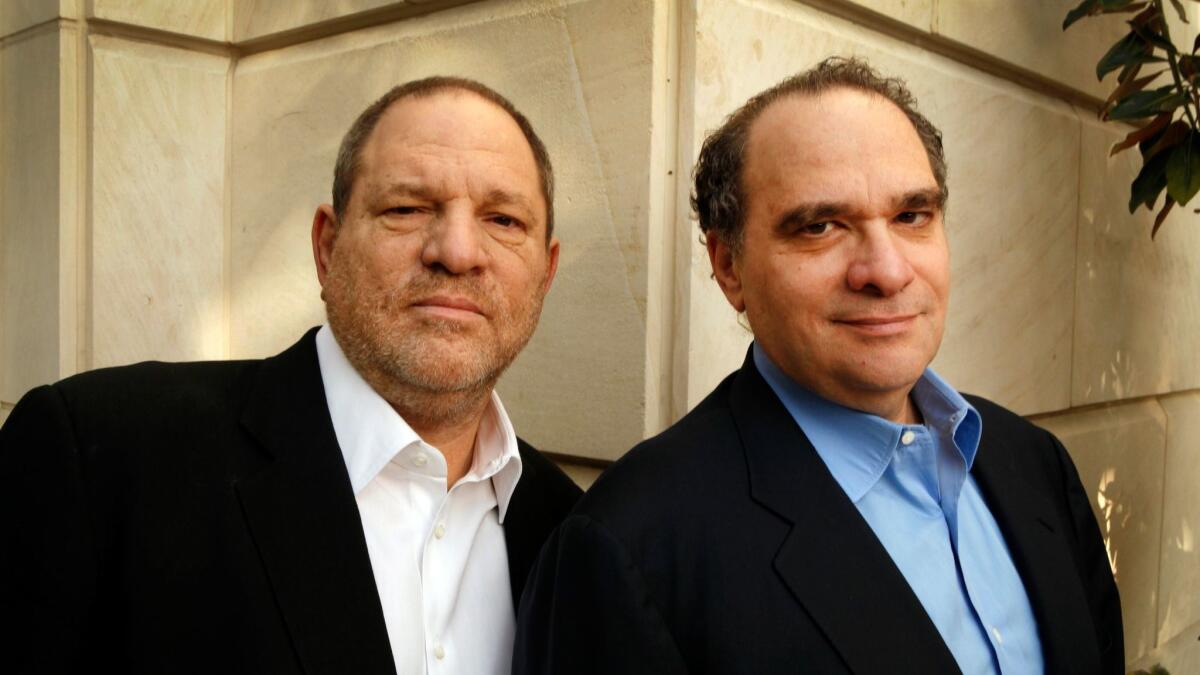

In an interview, Weinstein was alternately jovial, enthusiastic and defensive while also dispensing a decent amount of salty language. The producer-distributor is the same larger-than-life personality as he’s always been. But the company he runs with his brother, Bob, is changing by embracing streaming TV and cable programming as a component as important, if not more so, as its prestigious theatrical arm.

“TV at this point of my career is more lucrative and a lot easier to do,” said Weinstein. “When you’re making movies, you’re walking the high wire.”

He should know. Recent disappointments include the boxing drama “Hands of Stone” and the critically acclaimed “Sing Street.” “Your board is there to make money and sometimes I choose a little stubbornly not to make money,” said Weinstein. “I choose art over business.”

But the drama “Lion” has been a bright spot, and continues to do respectable business with plans to go nationwide this month as it builds awards momentum.

The theatrical business is “up and down like an EKG,” said Weinstein.

Industry experts said it would be unwise to underestimate the Weinstein Co.

“The one thing I have learned from competing with them is to never count them out,” said Joe Pichirallo, a former executive at Fox Searchlight and Focus Features, and now a professor at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts. “I have heard the death knell for the Weinsteins many times, only to see them roar back.”

At the height of his career at Miramax more than 15 years ago, Harvey Weinstein pioneered the concept “that awards are important to the marketing of independent films,” said Pichirallo. “But to compete, you have to spend millions, sometimes even more than what it cost to put a movie in theaters. He’s become a victim of a world he helped create.”

The fortunes of the 11-year-old Weinstein Co. remain murky since the privately held New York company is controlled by a group of nine shareholders, with the brothers retaining a 46% interest. The company has at least $505 million in financing from a group of institutions led by Union Bank.

Weinstein Co. could get an additional infusion of capital if its long-percolating plan to sell a stake in its TV division comes to fruition. Executives confirmed they are exploring a sale of a majority stake in the division that would allow the Weinstein brothers to remain involved in the management. A 50% sale would bring in about $300 million, executives said.

A deal with Britain’s ITV to acquire the entire TV division fell through in 2015. Weinstein Co. said it is being selective about potential partners.

Weinstein Co. said its TV division saw $31.6 million in earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization in 2015, and projects $50.6 million for 2016. But the rosy outlook doesn’t paint a complete picture since the company declined to disclose full financial results.

Last year, Weinstein Co. released just six movies in theaters (not including its genre division, Dimension), down from a high of 14 releases in 2014.

But executives plan to boost output this year, releasing up to 10 movies.

“Movies are still important for the kind of movies that work,” said Chief Operating Officer David Glasser. The company will focus “on the ones we know people will want to get off their couch to see.”

Since ending its tumultuous relationship with Disney under the Miramax brand in 2005, the New York-based mini-major studio has sought to diversify beyond Oscar-friendly films by expanding into new territory, most recently with projects at Netflix and Amazon. But these efforts have so far yielded mixed results — its “Marco Polo” series on Netflix was recently canceled — and have cost the Weinsteins millions.

The revolving door of executive talent has fueled additional talk about its stability. The company laid off about 20% of its workforce last year and currently has about 130 people.

Indie distributors face a world that is “mirroring the major studios in a feast-or-famine way,” said John Sloss, a producer and head of Cinetic Media, a film advisory management company.

Indie releases tend to either hit it big, like “La La Land” and “Manchester by the Sea,” or disappear quickly.

“Filmmakers are becoming less precious about having a big theatrical release,” Sloss said. “There’s less of a stigma about premiering on the small screen.”

Weinstein Co. is partnering with Amazon on two upcoming series from director David O. Russell and “Mad Men” creator Matt Weiner.

Harvey Weinstein said the company has already sold off rights to the Russell-directed series, a mob-themed story that costs $160 million and will star Robert De Niro and Julianne Moore. “We’re into profit. Very nice profit, by the way,” said Weinstein. “Everyone will be in very good shape before the camera starts.”

The company is also producing several cable projects, including the upcoming “Waco” miniseries on Spike; the Navy SEAL drama series “Six” on the History channel, debuting this month; and the long-running “Project Runway” reality series on Lifetime.

Weinstein Co. said it is looking to class up its unscripted TV slate to include talk and competition shows. In the past, the company made money off of low-brow reality series like “Mob Wives” and the trailer-park themed “Welcome to Myrtle Manor.”

“On a personal level, it’s not for me,” said Harvey Weinstein. “But we thank those shows for opening the door.”

Prestige is still a core value at Weinstein Co. “The Founder” has received glowing reviews as it prepares to open nationwide Jan. 20. The company paid a reported $7 million to distribute the movie, which is expected to gross between $5 million and $10 million on its first weekend in about 1,000 theaters.

It was first set to bow in the awards-friendly month of November, but was pulled in favor of “Lion” and relegated to August. Less than a month before opening, the company yanked the film again and set a limited release for Dec. 16.

But Weinstein Co. changed its mind a third time, and with little notice opened the movie on Dec. 7 for a weeklong, awards-qualifying run in one Los Angeles cinema. The equivocation hasn’t helped the film, which was once promoted as an Oscars contender for Keaton but has so far failed to garner much awards attention.

Studios frequently shift release dates, especially in the crowded month of December. But the Weinsteins have developed a reputation for turning the release-date game into an art form.

Instead, they’re pinning Oscar hopes on “Lion,” the uplifting drama about an adopted boy from India who attempts to locate his birth family using Google Earth. The movie, for which the studio paid $12 million, has so far grossed about $14 million since its November debut.

“Lion” resembles in some ways the kinds of small foreign films that Harvey and Bob Weinstein embraced when they launched Miramax in 1979. They were acquired by Disney in 1993, and hit a peak with “Pulp Fiction,” which remains the capstone of their long association with Quentin Tarantino.

The brothers later aimed for bigger glory and scored with Oscar winners like “The English Patient,” “Shakespeare in Love” and “Chicago,” as well as genre fare by Dimension, which is run by Bob Weinstein. But they clashed with Disney boss Michael Eisner and eventually parted ways.

They launched Weinstein Co. in 2005, raising close to $1 billion through Goldman Sachs. A string of flops led to a debt restructuring in 2010, and gave the investment firm and an insurance company some of the studio’s valuable library of 515 film titles (worth as much as $511 million, executives say).

Other ill-fated projects include an investment in the Halston fashion brand and the Broadway flop “Finding Neverland.”

“They spread themselves too thin and lost sight of the fact that they were good at indie films and genre films,” said one former Miramax executive who did not want to speak publicly to protect business relationships.

In 2010, the Weinsteins rebounded with “The King’s Speech,” which won the Oscar for best picture and became one of the company’s biggest box-office successes.

But the hits have become less frequent. In 2015, Tarantino’s “The Hateful Eight” underperformed domestically while “Woman in Gold” and Dimension’s family-oriented “Paddington” fared better.

Weinstein Co.’s last best-picture Oscar win was five years ago for “The Artist,” a movie that it acquired but didn’t produce.

Among some auteur filmmakers, Harvey Weinstein still has a negative reputation due to his famously abrasive personality and well-known penchant for reediting movies to his desire. Director James Ivory called him an “offensive creature,” saying that he attempted to recut two Merchant-Ivory productions, “Mr. and Mrs. Bridge” and “The Golden Bowl.”

“But Harvey never was able to touch those films,” said the three-time Oscar-nominated filmmaker. In the former movie, Weinstein backed down after star Paul Newman intervened; in the latter case, the movie found another distributor, Merchant-Ivory said.

“He has no respect for the artist,” said French director Jean-Pierre Jeunet, who worked with Weinstein on several films including the Oscar-nominated hit “Amélie.” “For him it’s material to make money.”

Weinstein released Jeunet’s most recent film — the English-language “The Young and Prodigious T.S. Spivet” — in a handful of theaters in 2015 with virtually no marketing after clashing with the director.

“I was punished for not obeying him,” Jeunet said. “Like he punishes all the directors who refuse to recut their film according to his wishes.”

Harvey Weinstein said he was trying to salvage flawed films. “Sometimes when there are problems — a movie is too long, or it has the wrong music — most of the time it’s worked out.” But when it hasn’t, “unfortunately you get tagged with names. The proof is in the pudding. And the proof is in the output. As I get older, I’m not up for these fights anymore …. I blame myself — I could’ve been a better manager and hope to be in the future.”

Next year, the company will be grooming two awards hopefuls — “The Current War,” starring Benedict Cumberbatch and Michael Shannon as Thomas Edison and George Westinghouse, and the New Testament-themed “Mary Magdalene,” with Rooney Mara in the title role and Joaquin Phoenix as Jesus.

The success of the company’s streaming and cable efforts remains “critical” for its survival, said Barry Avrich, director of the 2011 documentary “Unauthorized: The Harvey Weinstein Project.” “It might be the ultimate savior for him and other [indie film] companies.”

He added: “I think it’s a fools’ game to count him out. In ‘The Founder,’ the message is persistence. That’s Harvey. He keeps hustling.”

Twitter: @DavidNgLAT

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.