Should California spend $3 billion to help people buy electric cars?

The plan could lift state rebates from $2,500 to $10,000 or more for a compact electric car. (Aug. 28, 2017) (Sign up for our free video newsletter here http://bit.ly/2n6VKPR)

- Share via

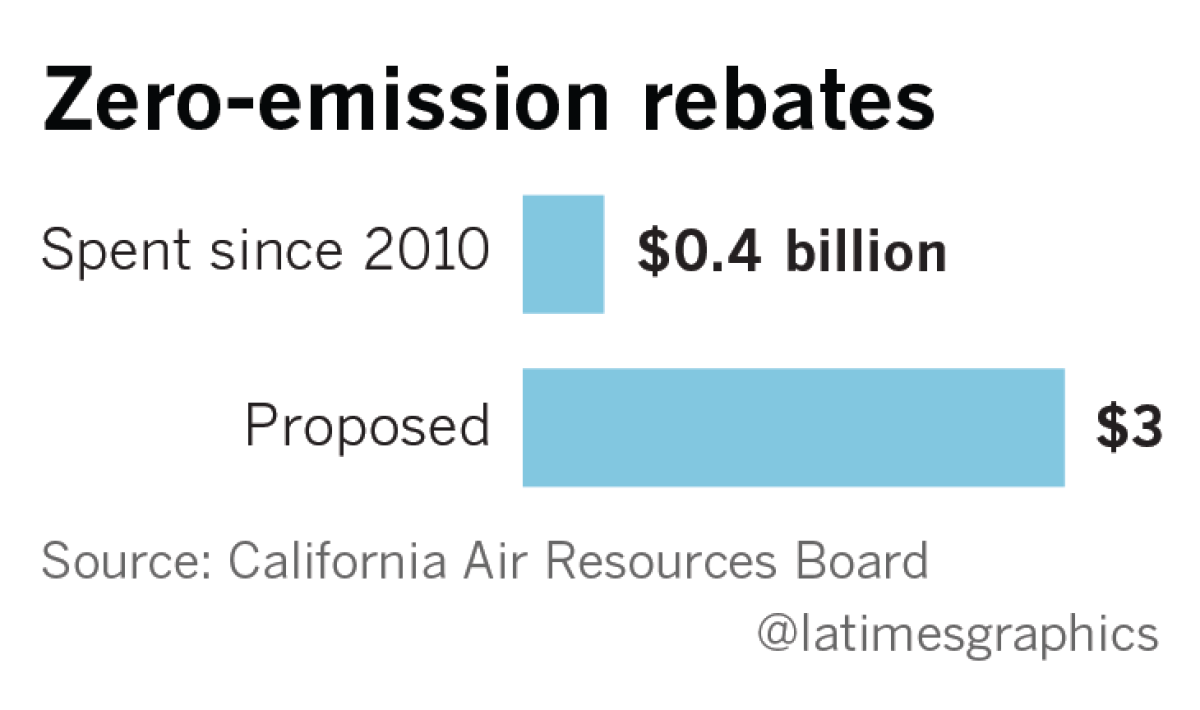

Over seven years, the state of California has spent $449 million on consumer rebates to boost sales of zero-emission vehicles.

So far, the subsidies haven’t moved the needle much. In 2016, of the just over 2 million cars sold in the state, only 75,000 were pure-electric and plug-in hybrid cars. To date, out of 26 million cars and light trucks registered in California, just 315,000 are electric or plug-in hybrids.

The California Legislature is pushing forward a bill that would double down on the rebate program. Sextuple down, in fact.

If $449 million can’t do it, the thinking goes, maybe $3 billion will.

That’s the essence of the plan that could lift state rebates from $2,500 to $10,000 or more for a compact electric car, making, for example, a Chevrolet Bolt EV electric car cost the same as a gasoline-driven

Already approved by several Senate and Assembly committees, the bill will go to Gov. Jerry Brown for his approval or veto if the full Legislature approves it by the end of its current session on Sept. 15.

California aims to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 to a level 40% below what they were in 1990, while also reducing other air pollutants. “If we want to hit our goals, we’re going to have to do something about transportation,” said Assemblyman Phil Ting (D-San Francisco), sponsor of Assembly Bill 1184.

Without a dramatic boost in subsidies, Ting said, the state risks falling short of Gov. Brown’s goal of 1.5 million zero-emission vehicles on California highways by 2025, and the California Air Resources Board’s goal of 4 million such cars by 2030.

The bill is opposed by Republicans averse to taxpayer subsidies and even the Legislature’s own analysts have called it “duplicative,” “unclear” and “problematic.”

Some Democrats also are casting a wary eye on new state spending, given California’s frequent budget crises.

Outside observers and analysts raise eyebrows at the $3-billion budget line. Supporters say the money will come mainly from the state’s cap-and-trade auction revenue, although they are vague on details. Other legislators, including Senate leader Kevin de León (D-Los Angeles), are putting in their own bids for cap-and-trade revenue that overlap with Ting’s.

“There are a lot of claims on that money,” said Severin Borenstein, an energy markets expert at UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business. Cap-and-trade revenue is not free money, he noted. “Voters should think of it as government revenue that could be used for anything else.”

Also left vague is the rebate amount to be applied to each vehicle. The bill passes that decision to the air resources board. It directs the board to use state rebate money so the consumer needn’t pay more for an electric compact car than a similar gasoline-powered compact car.

The reason electric cars cost more than traditional cars is because electric car battery packs still cost thousands more than internal combustion engines. Other market forces are working against electric cars, as consumers shift in large numbers toward big gas- and diesel-powered SUVs, pickup trucks and crossover vehicles as fuel prices remain persistently low.

Big state rebates on the spot

Ting’s basic argument in favor of the bill is that bigger rebates will lead to bigger sales, especially now that automakers are coming out with electric cars that can travel 200 miles or more on a single charge.

That alleviates “range anxiety,” he said, moving buyers’ attention to the price. He acknowledges that other factors are at play, including a perceived scarcity of public charging stations and lack of enthusiasm at many car dealerships.

Unlike the current program, rebate amounts would start high and then step down to lower amounts as total sales volume increases over the years.

“A lot of this is based on the belief that the price of batteries will come down and the price of vehicles will come down and will reach a crossover point when the price of a battery electric vehicle will be cheaper than an internal combustion engine car,” said Steve Chadima, senior vice president at Advanced Energy Economy, a renewable energy advocacy group.

The bill would also make it faster and easier to get a rebate. Now people purchase a car, apply for a rebate, and wait for a check from the state treasury. The new approach would subtract the rebate amount off the sale price, and the state would send the money to the dealer.

In effect, the plan would operate like regular cash-off dealer incentive programs, except that the state, not the manufacturer, would pick up the tab.

Rebate amounts would be based on the difference in price between an electric compact car and a comparably sized gasoline-powered car, “so that if people really want an electric, price is no longer the issue,” Ting said.

The legislation leaves it up to the Air Resources Board to figure out which cars are comparable, devise a formula and set rebate amounts.

“For argument’s sake, what we have assumed is the price of a long-range, compact EV — in this case we’re using the Chevy Bolt EV as the benchmark — and compare that to an equivalent internal combustion engine car,” Chadima said.

The base price of a Bolt EV is $36,620 while the price of a base Civic is $18,740. Take off $7,500 for the federal government’s EV subsidy and, accounting for Chadima’s example and the bill’s language, the state would contribute $10,380 to the purchase.

The Tesla factor

The bill would also allow, but not require, the Air Resources Board to make up for the $7,500 federal tax rebate should it disappear under the Trump administration or should a particular manufacturer sell enough cars that the federal subsidy is no longer available.

Federal subsidies wind down once an automaker sells a total of 200,000 electric cars. Tesla Chief Executive Elon Musk says his company will turn out 500,000 vehicles in 2018, now that the Model 3 is under production, which would end federal Tesla subsidies.

That is why some in Sacramento call Ting’s legislation the “Tesla bill.” Supporters of the bill deny it is tailored to help that company in particular.

The base price for a Model 3 is $35,000. If the state were to match the price of a Honda Civic and also cover an expired federal rebate, the buyer incentive would total $16,260 per Model 3.

The Financial Times recently reported that BCA Research, an independent investment research firm, estimated that, excluding subsidies, the cost of an electric car now is $16,000 more than an equivalent internal combustion engine car.

Chadima does not dispute that analysis. But “the assumption that the [federal] tax credit will go away or that any manufacturer would have reached a limit is not part of our particular calculations.”

The bill contains no language specific to Tesla or any other manufacturer, and doesn’t explicitly call for making up for a federal subsidy shortfall.

Tesla declined to comment. In its second-quarter shareholder update this year, the company said, “Model 3 has been designed to be affordably priced and to provide compelling customer value, even without government incentives.”

Used cars and arbitrage opportunities

The bill also expands the state’s “cash for clunkers” program, which pays out $1,000-$1,500 for qualified, decades-old cars to get high-pollution vehicles off the road. And it adds rebates for the purchase of used electric cars.

Funding for both programs, Ting said, would rise to $60 million from $30 million.

Ting defended the used car rebate as a way to broaden the demographics of electric car owners.

“Right now a used [all-electric] Nissan Leaf that’s coming off a lease is going for like $7,000 or $8,000. So we could have some more incentives, so more people in moderate-income communities could actually afford that car,” Ting said.

The rich rebates would create a big price gap between cars sold in California and in other states. That has led to speculation that the system could be exploited to buy cars in California with state rebates and sell them for thousands more elsewhere.

“I think selling cars is hard enough,” Ting said. “I don’t think anybody would do that business. You could bring up any number of hypotheticals, sure. Georgia just got rid of its electric vehicle subsidy. I haven’t heard of anybody coming here to do that arbitrage.”

A money mystery

It’s yet to be determined where the bill’s $3 billion will come from.

When Ting presented the legislation earlier this year, it called for the state’s electric utilities to bill customers to pay for motor vehicle subsidies. Politically, that did not fly. So a $500-million annual appropriation was put in the bill, which would add the money to the state’s greenhouse gas reduction spending. Fellow legislators didn’t like that, either, and Ting plans to remove the $500 million annual requirement.

The bulk of the money, Ting said, would come from the state’s cap-and-trade auction revenue, which funds the current rebate program. Under cap-and-trade, the state sets an upper limit on greenhouse gas emissions, and a market is created for rights to pollute beneath that limit.

Between 2013 and 2016 cap-and-trade auctions raised about $4.4 billion for the California treasury. That pays for a variety of programs, including high-speed rail, as well as clean-air buses and heavy-duty trucks.

The cap-and-trade program was recently extended to 2030, but future auction proceeds are uncertain. New spending on rebates from cap-and-trade would cut into other greenhouse gas programs, including mass transit.

The bill, Chadima said, directs the Air Resources Board “to look at the range of sources of funding that they have available to them.” That includes cap-and-trade revenue, “but also a number of other sources, and to pull together a portfolio of funding so that the program can be continuously funded,” he said.

What other sources? “We’re in the process of discussing that right now,” Ting said.

ALSO

Harley's new hogs, ready for the 21st century

Volkswagen engineer gets prison term and $200,000 fine in emissions-cheating case

For lovers of vintage cars, DriveShare is the new place to rent (or rent out) your ride

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.