How free coupons for patients help drugmakers hike prices by 1,000%

- Share via

Horizon Pharma charges more than $2,000 for a month’s supply of a prescription pain reliever that is the combination of two cheap drugs available separately over the counter.

Another company, Novum, sells a small tube of a prescription skin rash cream, containing two inexpensive decades-old medicines, for nearly $8,000.

What is key to the companies’ business plan of raising prices by 1,000% or more?

The answer: coupons that deliver Horizon’s pain reliever Vimovo and Novum’s skin cream Alcortin A for as little as nothing to the patient, while leaving America’s health system to pick up much of the rest of the price.

Experts warn that the coupons, increasingly being used by dozens of companies, are sharply adding to the nation’s medicine bill. That cost is passed along to most Americans through higher insurance premiums and taxes needed to pay for government health programs.

The success of Horizon and Novum using this strategy demonstrates how America’s convoluted and opaque system of paying for prescription drugs enables executives to set extraordinary prices on modest medicines that have been around for years. The coupons keep patients and doctors from seeing the medicine’s true price tag.

“Via a coupon, the manufacturer can make its high-priced drug look as cheap as these over-the-counter medicines,” explained Matt Schmitt, an assistant professor at the UCLA Anderson School of Management.

In two recent papers, Schmitt, along with professors from Harvard and Northwestern, showed how the coupons propelled companies to charge “the highest price possible.”

They found that spending on 23 medicines sold through coupons was as much as $2.7 billion higher over five years than it would have been if the coupons were not used.

In 2007, a quarter of sales from brand-name medicines came from drugs backed by co-pay coupons, the group said. By 2010, that proportion had more than doubled and “the availability of coupons has since become rampant,” they said.

By boosting prices, companies can bolster revenue without spending more on research to discover new medicines. Horizon, for example, has increased the price of Vivomo eight times in the last two years. The price hikes lift the corporate bottom line, and often executives’ compensation.

Last year, Horizon’s board handed Chief Executive Timothy Walbert a pay package worth $93.4 million – a 10-fold rise from the previous year.

Novum, founded last year and owned by a small group of investors who don’t release financial figures, has sold more than $85 million worth of Alcortin A this year through the end of July, according to QuintilesIMS, which tracks drug spending. Before Novum bought the drug from another company, the prescription skin cream’s annual sales were less than $4 million.

Of the three medicines Novum sells, Alcortin A is by far its most popular.

In answers to questions sent by email, Geoffrey Curtis, Horizon’s senior vice president of corporate communications, said the coupons help patients get needed medicines.

“Our goal is to provide access to medicines a patient’s physician prescribes while limiting the patients’ financial burden,” Curtis said.

He said the wholesale price of the company’s pain reliever Vimovo “is not reflective of the cost to patients.”

Rand Walton, a spokesman for Novum, declined to answer questions about its skin cream. In a statement, Walton said Novum was owned “by a group of like-minded investors who believe in the company’s business model to provide no-hassle and affordable access to therapies.”

Some patient advocacy groups support industry coupons, a position that has somewhat muffled the outcry over soaring medicine prices.

“Co-pay coupons are something our case managers will continue to use until there’s no need for them,” said Caitlin Donovan at the National Patient Advocate Foundation. The group, which is partly funded by drug companies, runs a program to help patients pay for medicines.

Alcortin A is a combination of hydrocortisone and an antibacterial drug called iodoquinol – both discovered many decades ago. The gel also includes a compound from the aloe vera plant, similar to what is sold to soothe sunburn. Its label explains that it is “possibly” effective for eczema and other skin conditions.

Horizon’s Vimovo is a combination of naproxen, the generic pain reliever sold under the brand name Aleve, and the generic version of the heartburn medicine Nexium. Both are available over the counter. Some doctors suggest taking the two medicines together to try to avoid stomach ulcers, a dangerous side effect of pain relievers, like Aleve, known as NSAIDS.

The wholesale, or list price of Vimovo is $34 per tablet. The pain reliever is taken twice daily for a total cost of $68. If a patient instead bought naproxen and Nexium over the counter at the drugstore, a day’s worth of medicine would cost as little as 57 cents.

Horizon bought the rights to sell Vimovo and quickly raised its price for 60 tablets from $115 to $799 on Jan. 1, 2014, according to data from Truven Health Analytics. After seven more price hikes, the drug now sells for $2,061.

Curtis, the Horizon executive, said the combination drug is worth its price because it lowers a pain patient’s risk of potentially deadly ulcers. “To assume that you can substitute OTC [over the counter] and/or generic medicines sequentially is inaccurate,” he wrote in an email.

The strategy of purchasing an older medicine and hiking its price has become so common in the pharmaceutical industry that Wall Street analysts call it “buy-and-raise.”

Last year, executives from Valeant Pharmaceuticals International and Turing Pharmaceuticals were called before a congressional committee to explain their large price hikes on medicines purchased from other companies.

Novum bought the rights to sell Alcortin A in the spring of 2015 and soon hiked its price from $189 to $2,496, according to Truven. The price jumped to $3,489 in January and to $7,968 on Sept. 12.

Experts say it would be far more difficult for drug companies to aggressively boost prices without the coupons. They defeat one of the few tools that the nation’s health system has to try to stop doctors from prescribing high-priced medicines not worth their cost.

Insurers often put higher co-payments or co-pays — the fixed payment made by a patient — on expensive, brand-name drugs in an attempt to get patients to take cheaper generic alternatives. With the coupons, though, patients and doctors don’t have to worry about those higher co-pays.

But experts say widespread use of the coupons leads to overall higher premiums. “This is raising the cost to everyone,” said Steve Miller, chief medical officer at Express Scripts, the nation’s largest manager of prescription drug benefits for insurers and employers.

Last year, drug costs for patients covered by private insurance policies rose nearly 16%, according to the S&P Global Institute.

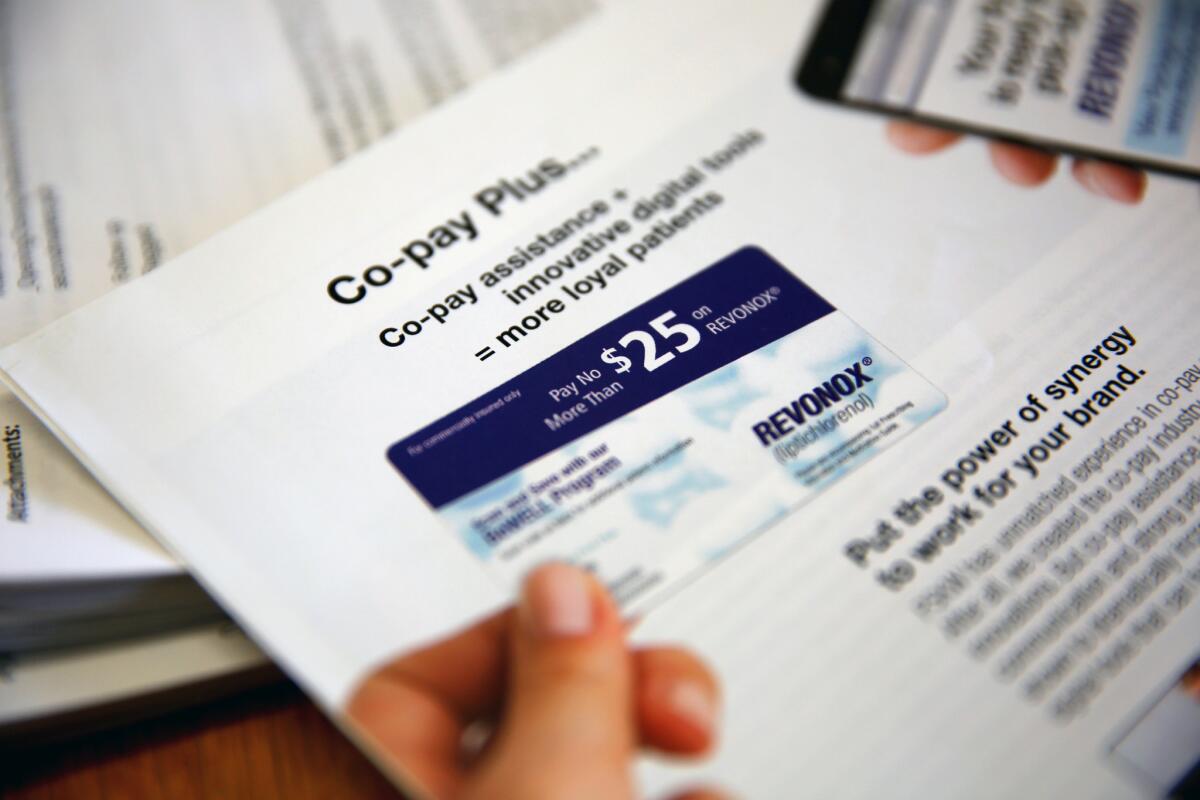

Patients can find the coupons on Internet sites and in drug ads in magazines. Pharmaceutical salespeople deliver handfuls of them to doctors’ offices. Consulting firms embed the coupons on electronic prescribing services so that doctors see them on their mobile devices.

The coupons are submitted to the pharmacy with the patient’s prescription. The drug companies have hired firms that specialize in making the process fast and easy for patients and physicians.

Horizon said it spent more than $1 billion last year on coupons and other financial assistance for patients.

The companies’ coupon strategy only works if insurers continue to include the drugs on their lists of covered medicines, known as formularies, and pay for the cost that the coupons don’t cover.

Some insurers, including Express Scripts, have tried to put up roadblocks to the exorbitantly priced drugs by removing them from their formularies.

But Horizon and other companies have learned how to keep the number of prescriptions rising despite the cutoff from some insurers.

With the help of electronic prescribing systems, Horizon has doctors send the medicine order with a few taps on their mobile device to mail-order pharmacies that the company has partnered with, according to its annual report filed in 2014. The pharmacy ships the pills to patients overnight.

The mail-order pharmacies fill out paperwork required by insurers when doctors say patients need medicines that have been excluded from the formulary.

Horizon executives have explained to investors and analysts that fewer prescriptions have been rejected for payment by insurers when they are sent through the mail-order pharmacies.

Miller at Express Scripts said the firm had found the mail-order pharmacies resubmitting claims that had originally been rejected. The drug is so inexpensive to manufacture, he said, that if just some of the prescriptions are eventually approved for payment by insurers the companies still make money.

“This is people profiteering off sick individuals,” Miller said. “It’s very unfortunate.”

Doctors wrote more than 95,000 prescriptions for Vimovo in the first three months of the year, according to Horizon. That was 40% more than in those same months the year before.

Curtis said the decision of which pharmacy to use was “between the physician and the patient.”

As an incentive to use the mail-order pharmacy, Horizon guarantees that the patient will receive those prescriptions even if the insurer doesn’t pay.

Breast Cancer Action, a patient advocacy group that does not accept donations from drug companies, opposes the coupons, saying they can lead patients to choose a medicine with higher risks or that is not best for their condition.

“They allow corporations to look like good corporate citizens,” said Karuna Jaggar, the San Francisco-based group’s executive director, but are actually “a thinly veiled program to drive up revenue.”

“Coupons are not the answer” to high drug prices, Jaggar said. “There should be cost controls to make sure patients aren’t being left out.”

The industry doesn’t give coupons to patients covered by Medicare or other federal healthcare programs. That’s because the federal government has long viewed the coupons as illegal kickbacks given to get doctors to prescribe high-priced drugs.

That ban has created harsh surprises for some patients who say they need the drugs.

Jim McCamphill, 71, of Venice, Fla., said Alcortin A is the only medication that works for a recurring skin rash.

His doctor gave him a free sample, he said. But now, even though he tries to limit his use, McCamphill said he is running out. His pharmacist told him that for Medicare patients who can’t use a coupon, the next tube would cost $9,373.

“It’s a question of do you eat or do you put on an ointment?” McCamphill said. “It’s a disgrace. The system is so skewed, it’s scary.”

To read the article in Spanish, click here

Follow @melodypetersen on Twitter

MORE BUSINESS NEWS

The rise of sports TV costs and why your cable bill keeps going up

What does it take to get banned for life by an airline? Ask this Trump supporter

Supersonic passenger planes may begin test flights next year

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.