Column: How the hospital lobby derailed legislation to protect you from surprise hospital bills

- Share via

California hospitals want you to know that they’re fully on board with the idea that emergency room patients shouldn’t be hit with thousands of dollars in surprise billings because the ER isn’t in their insurance plan’s network.

You should also know, however, that the hospitals just killed a measure in Sacramento that would have accomplished that goal, and that the reason they did so was to protect their own revenues.

The legislation is Assembly Bill 1611, which was introduced in February by Assemblyman David Chiu (D-San Francisco), and sponsored by the patient advocacy group Health Access California and the California Labor Federation.

The Assembly passed the bill in May, then it languished in a Senate committee until it was withdrawn by the sponsors July 10. The measure was explicitly a response to investigative reporting about Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital, which was found to be saddling ER patients with surprise bills sometimes reaching into the tens of thousands of dollars.

Every hospital CEO has the cellphone number of his state senator and assemblyman.

— Anthony Wright, Health Access California

San Francisco General could do this because it had not signed network contracts with any health insurers. Network contracts establish a rate for all treatments and forbid providers to bill a health plan’s members for any additional sum. As an out-of-network hospital, San Francisco General could charge patients any sum it chose. Health insurers typically covered the bills only up to the standard in-patient rates for such out-of-network ER services. That left the patients on the hook for the rest, a practice known as balance billing.

In our fraught debate over healthcare, two principles seem to win support from Democrats, Republicans and independents: People with preexisting conditions should be protected, and “surprise” medical bills should be banned.

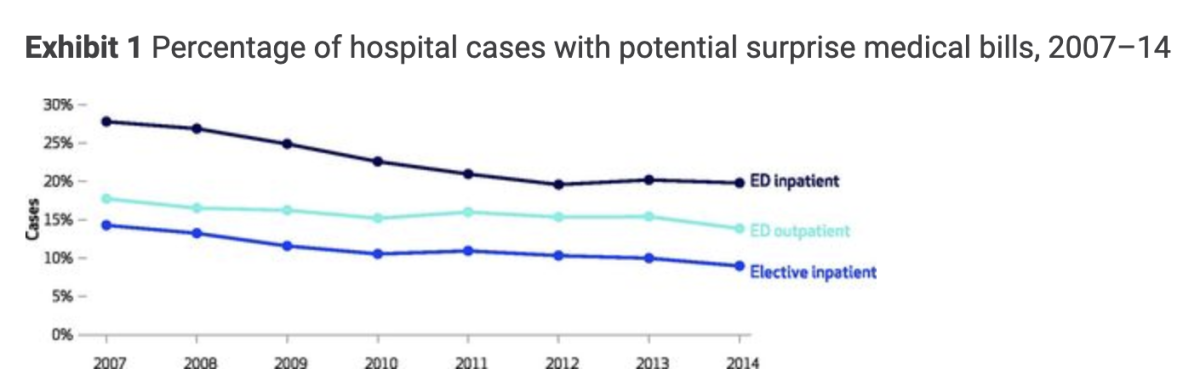

San Francisco General was the most notable offender, but the problem extended statewide — it could happen to any patient showing up at a hospital that was out of his or her insurance carrier’s network. Emergency rooms are the most obvious problem points because patients normally don’t have much choice in selecting one. Whether they arrive under their own steam or are brought by ambulance, they may not be in a condition to check first whether the ER is in their network. A 2017 survey by the Federal Trade Commission found that 14% of outpatient emergency room visits nationwide could lead to a surprise bill.

Chiu’s legislation had two major pieces. It prohibited hospitals from charging out-of-network ER patients more than they would charge an in-network patient for the same services. It also established a standard for what a hospital could charge a non-network insurer. In other words, the bill limited what patients would pay hospitals out of pocket but set rules on what insurers would pay the hospitals too.

Originally, the bill set 150% of Medicare reimbursement as a payment benchmark. The sponsors eventually amended that to whatever rate is “reasonable and customary,” defined as the average in-network contracted rate in a hospital’s geographic region. Hospitals could appeal for higher reimbursements through the state Department of Health Care Services.

The state’s hospitals went to the mattresses over the payment provision, cursing it as “government rate setting” that they would never accept. Hospital executives inundated legislators with warnings that rate-setting would force their institutions to shut down.

“We have 450 hospitals in California,” says Anthony Wright, executive director of Health Access, “and every hospital CEO has the cellphone number of his state senator and assemblyman. A hospital saying it would close would give pause to any lawmaker.”

The University of California regents are wrestling with a question that should have an easy answer: Should they approve an “affiliation” between UC San Francisco, one of the leading teaching hospitals in America, and Dignity Health, a Catholic hospital chain that openly discriminates against women and LGBTQ patients and requires its doctors to comply with religious directives, some of which run counter to medical science and ethical practice?

The proponents were aware that they were poking a stick into a tiger’s cage. “We’re going after a practice that has generated billions of dollars in profits for hospitals, Chiu told me, “and hospital CEOs around the state waged very aggressive lobbying to protect those profits.”

He might have added that the hospitals could put their money where their mouth is. The big hospital chains Sutter Health and Tenet have spent about $1 million between them on Sacramento lobbying since 2017. The California Hospital Assn.’s political action committee has made $250,000 in campaign contributions so far this year, and its “committee on issues” holds a war chest of $9.7 million, according to its most recent public disclosures.

Chiu’s legislation built on existing California law, which prohibits most balance billing by out-of-network doctors treating patients at hospitals that are in the patients’ network. This rule prevents a non-network radiologist reading a patient’s X-rays at a network hospital from issuing the patient a surprise bill, for example. The law, which went into effect in July 2017, forces health plans and providers to work out billing issues between themselves, leaving the patients out of it. But it doesn’t apply to self-insured employer plans because they fall under federal law. Chiu tried to get around the federal preemption by imposing the rate standards on hospitals because they’re state-regulated. Thus was the battle launched.

For the record, the hospitals agree that “if a hospital is not in your insurer’s network, what you should pay is only what you would pay at an in-network facility,” in the words of Jan Emerson-Shea, vice president for external affairs at the hospital association. On the surface, that places the hospitals on the consumers’ side. Emerson-Shea says the hospitals were on board with AB 1611 until it was amended to incorporate “an unrelated provision having to do with rate setting, which has nothing to do with protecting patients.”

This is an absurd, if not flagrantly cynical, assertion because rates and consumer protection are inextricably entwined — no system protecting patients from surprise hospital billing could exist unless rates are regulated somewhere within the system. The hospitals refuse to say who should pay for patients’ emergency care, if not the patients. The hospitals say that, whoever does pay, it won’t be them. The obvious implication is that it should be health insurers.

The debate over hospital mergers traditionally has focused on whether allowing hospitals within a local community to merge drives up prices in that community.

The hospitals won’t say so outright. “We are not getting into that, that is not our role,” Emerson-Shea told me. You can be forgiven for thinking that this resembles the line from the satirical songwriter Tom Lehrer about Wernher von Braun — “‘Once the rockets are up, who cares where they come down? That’s not my department,’ says Wernher von Braun.” The hospitals are taking a position with vast implications for millions of Californians who might be vulnerable to surprise ER billing, and saying that the impossibility of dealing with their obstinacy is not their department.

Indeed, the hospitals want to blame surprise billing for ER services entirely on health insurers. “The reason patients find themselves in an out-of-network situation is because an insurance company declines to contract with a hospital,”Emerson-Shea said.

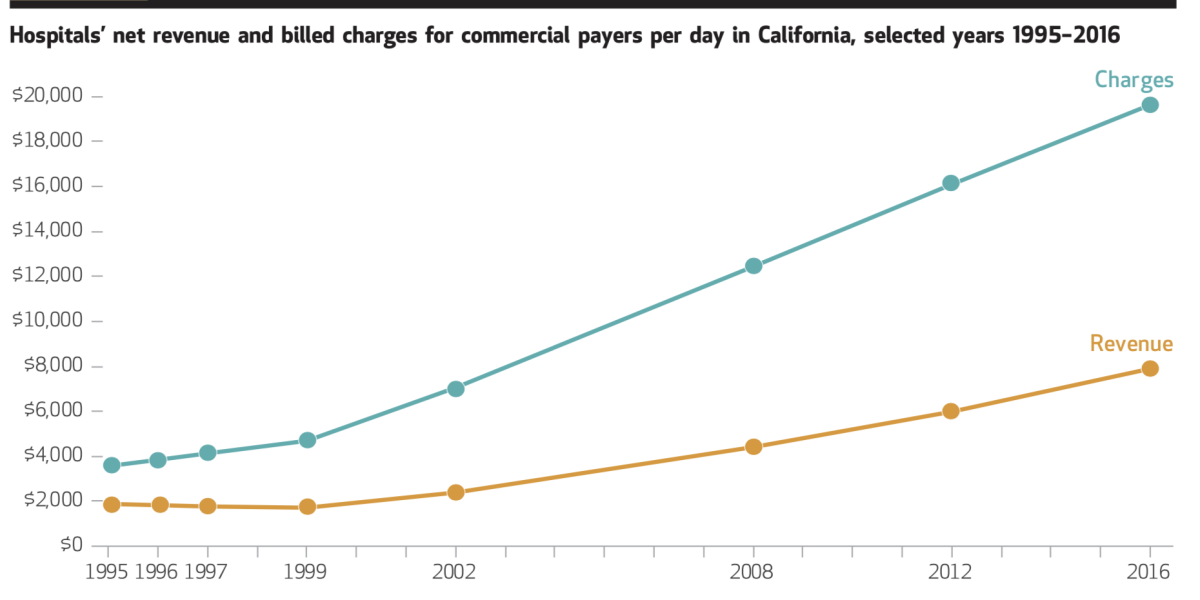

Independent research, however, tells a different story. The reason hospital ERs remain outside so many health plan networks, according to a 2018 study led by Glenn Melnick of USC, is that a well-meaning California regulation encouraged the trend. This “prudent layperson” rule, adopted in 1999, required health insurers to instruct their members to go to the nearest ER in an emergency and for the insurers to pay, even if the ER was out-of-network. But the rule didn’t set standards for how much the hospitals could charge.

Therefore, Melnick observed, “hospitals gained a guaranteed flow of local patients with a medical emergency for whom they could charge above-market prices.”

In the last few years, Anthem Blue Cross has made a strong bid for the award for the most heartless and senseless coverage policy in the health insurance business.

Meanwhile, a wave of hospital mergers gave the hospitals even more bargaining power. The quintessential example is Sutter Health, the nonprofit hospital chain that dominates in Northern California, and which Atty. Gen. Xavier Becerra has accused of ruthlessly exploiting its size and reach to extract “illegally inflated prices” from insurers, employers and patients. Becerra’s lawsuit against the chain, filed in March 2018 in San Francisco County Superior Court, is pending.

In its defense, Sutter has asserted that it sets prices for private insurers in part to “cover losses on government payors [that is, Medicaid and Medicare], to cover charity care and community investment” and to pay for maintenance and technology improvements.

The claim that fees charged to private insurers are high in order to subsidize losses from Medicaid, Medicare and charity care is the hospital lobby’s most common defense of those fees. But the argument is specious. “In truth, it’s been nearly two decades since any rigorous study has found evidence of substantial cost shifting,” health economist Austin Frakt of Veterans Affairs reported in 2017.

The evidence is largely to the contrary. The chief factor governing how much hospitals charge private insurance companies is the level of hospital competition within a region — in other words, the leverage that hospitals can exert over insurers. A 2010 study by the government’s Medicare Payment Advisory Commission found that when hospitals are able to extract higher reimbursements from private insurers, that often makes their Medicare and Medicaid rates look less profitable, even if they’re not.

When big hospitals merge, the merger partners’ mantra is almost always the same: The deal will deliver lower costs to the lucky patients, with no sacrifice in quality.

Hospitals that can squeeze private insurers for generous reimbursements spend more lavishly, which allows their costs to go up. Because Medicare and Medicaid rates are fixed, they appear to force the hospitals to treat their enrollees at a loss. But it’s the hospitals’ cost structures that cause the problem, not the reimbursement rates.

The backers of AB 1611 are girding to bring the measure back to the Senate next year. They say they’re trying to work out an option that would satisfy the hospitals. But it’s hard to conceive of a solution if the hospitals remain adamantly opposed to any rate regulation at all. One change may come from Washington, where congressional committees are pondering several bills that would comprehensively outlaw surprise billing. Stories like those emanating from San Francisco General can be powerful goads to federal lawmakers. But hospitals have powerful lobbyists in Washington too.

The question is how long hospitals can hold the line against some form of rate regulation, especially if the nation’s healthcare system gets reworked by Democrats in Congress and a Democrat in the White House. The ground may be shifting beneath the hospitals’ feet, but so far they don’t seem to be feeling the tremors.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.