Column: Two billionaires explain why they shouldn’t pay more taxes, unlike you poor saps

- Share via

Statements by billionaires explaining why they already pay plenty in taxes and shouldn’t have to pay any more have become so much a part of the political landscape that they deserve a “Jeopardy!” category all to themselves.

A new op-ed on this theme, penned for the Tuesday Wall Street Journal by Home Depot co-founder Bernard Marcus and New York supermarket magnate John Catsimatidis, sets a standard for the genre that other tycoons will shoot for in vain. Let’s take a look.

In their very first sentence, the authors declare, “The two of us are quite rich” -- thereby instantly establishing their piece as the Platonic ideal of Wall Street Journal op-eds.

Every additional dollar the government takes from us is a dollar less for this critical process of expanding America’s wealth and job-creating businesses.

— Billionaires Bernard Marcus and John Catsimatidis

The rest of the piece, which is headlined “Making Money is a Patriotic Act,” is notable for the self-refutation embodied in the rest of that opening paragraph. Its second sentence reads, “We have earned more money than we could have imagined and more than we can spend on ourselves, our children and grandchildren.” Then comes sentence 4: “But we have nothing to apologize for, and we don’t think the government should have more of our profits.”

In other words, they have more money than they can spend, but they don’t want to give it up on any but their own terms.

You may remember all the glowing predictions made for the December 2017 tax cuts by congressional Republicans and the Trump administration: Wages would soar for the rank-and-file, corporate investments would surge, and the cuts would pay for themselves.

Who should have more of their profits, then? The answer is a common one in essays like this: They’ll decide for themselves.

“We know we can spend our dollars more wisely, and in ways that benefit our communities and our country, than politicians can,” they write. (My mother would paraphrase their theme as “I like me, who do you like?”)

This is the crux of the billionaire’s anti-tax screed the world over, so it’s worth examining in detail.

The Marcus-Catsimatidis essay is structured as a counterpunch to the “patriotic millionaire” movement, through which some members of the 0.1% have cited America’s “moral, ethical and economic responsibility to tax our wealth more.”

A few years ago, the joke going around was that a cocaine habit was God’s way of saying you have too much money.

In a June 24 open letter to “2020 Presidential Candidates,” 19 billionaires declared that a wealth tax, say like the one advocated by Democratic candidate Elizabeth Warren, would be “a key to both addressing our climate crisis, and a more competitive, stronger economy that would better serve millions of Americans.... It is not in our interest to advocate for this tax, if our interests are quite narrowly understood. But the wealth tax is in our interest as Americans.”

Among the signers are George Soros, Facebook co-founder Chris Hughes, venture financier Nick Hanauer, and heiress Abigail Disney. Los Angeles billionaire Eli Broad endorsed the movement with an op-ed of his own the day after the letter appeared.

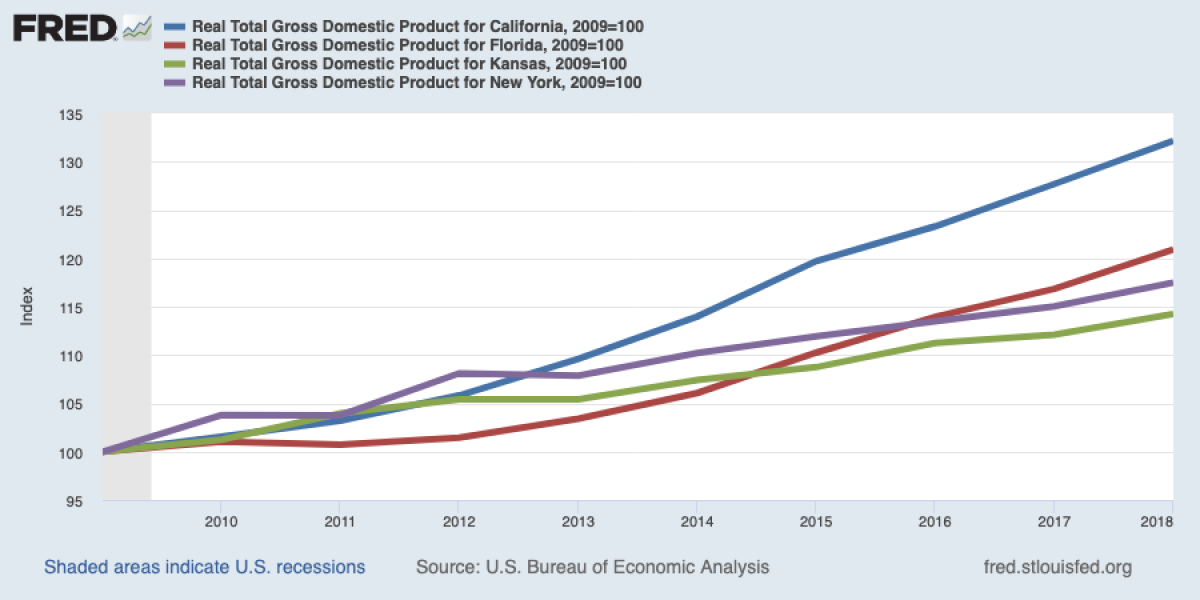

Marcus and Catsimatidis argue against higher taxes by asserting that “the evidence is clear that higher tax rates would hurt the global competitiveness of the American economy, and thus hurt all Americans. One of us lives in Florida, where there is no state income tax; the other in New York City, with the highest income taxes in the country. The Empire State is struggling compared with other states; the Sunshine State is booming.”

This is a masterpiece of cherry-picking. Yes, since the last recession Florida’s economy has grown faster than New York’s. But that’s hardly the whole story. The most highly taxed state in the nation is California, which also is the fastest-growing state. The poster child for state tax-cutting is Kansas, which has become an economic black hole.

Incidentally, Catsimatidis identifies himself as “honorary chairman of the Committee to Unleash Prosperity,” which turns out to be an anti-tax group co-founded in 2015 by economist Art Laffer and Steve Moore, who promoted the Kansas model and have been pushing half-baked and unsuccessful economic policies for years.

It’s a safe bet that President Trump will devote part of his State of the Union address Tuesday night to talking up the great virtues of the tax cut he signed into law just before Christmas.

The authors make their case in part by citing their philanthropic endeavors. They say they have “given more than $2 billion to charity—causes ranging from the American Cancer Society to the Salvation Army, from museums and operas to veterans programs, homeless assistance and private schools in inner cities for at-risk kids.” (They don’t mention that, based on their presumed tax brackets, about a third of those donations are subsidized by other taxpayers, since they’re tax-deductible.)

What gets slighted in that list are items like roads and bridges, government services such as police and fire protection, public schools and teachers. In short, infrastructure and services that government funds from tax revenue. Can the charitable efforts at homeless assistance and private schooling in inner cities that Catsimatidis and Marcus crow over fill the funding gap for public programs? Plainly not.

The authors also boast about “our enterprises...helping cure terrible and painful diseases from cancer to multiple sclerosis.” For perspective, consider that the single biggest funding agency of biomedical research in the world is the National Institutes of Health. The budget for the NIH, however, has consistently come under attack by the Trump administration, which this year proposed to cut it by $5 billion, or 13%. The White House said the cuts reflected “priorities,” implying that they were made necessary by budgetary stringency -- fostered, in part, by the massive tax cuts enacted to benefit Catsimatidis and Marcus and their “enterprises.”

If you happened to check out the latest ranking of states for their “economic outlook” published last week by the right-wing political group ALEC, you would be excused for concluding that California is deep in an economic hole and digging itself deeper.

Could Marcus and Catsimatidis make up the NIH’s budgetary gap out of their own wisely apportioned resources? Forbes pegs Marcus’ net worth at $5.6 billion. and Catsimatidis’ at a measly $3.1 billion. So they could step in if they chose to spend almost all their money on this one effort, but that would leave nothing for museums, operas, etc.

They say that “when we look at the way government spends its money, we are frustrated by the waste and the ineffectiveness of so many of its programs, however well-intentioned.” This is the all-purpose dodge trotted out by every anti-tax warrior in existence, from the loftiest billionaire to the lowliest militiaman. It’s not as though private corporations are immune to waste and ineffectiveness, unless one considers the $5.2-billion quarterly loss recently reported by Uber to represent a triumph of the efficient allocation of capital.

Then there’s the irony that the essay by Marcus and Catsimatidis is transmitted to millions of readers via the internet, the product of a government program, or that the goods sold by Home Depot and Catsimatidis’ Gristedes supermarkets reached their shelves via the (federally funded) interstate highway system.

Marcus and Catsimatidis bolster their claim to perfect knowledge about how to spend their money by referring to their businesses, which they call “our legacies.” They grouse that “every additional dollar the government takes from us is a dollar less for this critical process of expanding America’s wealth and job-creating businesses.”

Monday being tax day, it’s only proper to deliver an important home truth to American taxpayers: You don’t pay enough.

That brings us to Home Depot, the legacy of Bernard Marcus, who co-founded the company and from which he retired as chairman in 2002. Home Depot was a beneficiary of the Republican tax cut of December 2017, which was supposed to bring prosperity to all Americans. The company followed the tax cut with one of the biggest stock buybacks in corporate America, a $15-billion handout to shareholders.

Employees, not so much. The company said the tax cut allowed it to pay bonuses of up to $1,000 to its workforce, but these turned out to be largely chimerical. Only workers with 20 years of service at the company would get the full $1,000, which would work out to about 48 cents an hour for full-time work. Others would receive as little as $200. And it’s proper to note that one-time bonuses are no substitute for raises, which keep on giving.

None of this is to say that Marcus and Catsimatidis aren’t charitable folks. Marcus, for example, has said he plans to give away most of his fortune. That doesn’t mean their claim that they already pay a fair share in taxes and shouldn’t have to pay more

isn’t greedy and arrogant. Their fortunes weren’t built by themselves alone, but developed from infrastructure and services that were funded by taxes; without their huge workforces, moreover, they would have nothing.

As for their assertion that they already pay their “fair share,” why should anyone trust them to be the judge? Their words remind me of my favorite economist’s line, penned by the conservative Herbert Stein, also in a Wall Street Journal op-ed (in 1996), in a piece discussing the justice of the progressive income tax.

Stein offered “one law derived from 60 years of observation...: “Whatever is the existing degree of progression, people who pay the top rate will think it is too much.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.