Seniors facing eviction fear homelessness and isolation as California’s housing crisis rolls on

- Share via

Mario Canel met his wife inside the apartment where he’s lived for the last 33 years.

Canel, a house painter, was at the Silver Lake complex off of Sunset Boulevard on a job, but he and his customer quickly connected over their shared Guatemalan roots. It wasn’t long before Mario and Sabina married, and her home became his. For years, they basked in such comforts as plucking chayote from a vine outside their front window.

When his wife died in April 2005, Canel was consoled with walks throughout the neighborhood and his connection to people inside the eight-unit bungalow court. It also helped that even as the surrounding neighborhood gentrified, rent control held his rent below $400.

But three months ago, a real estate investor purchased the complex and soon told all tenants to leave. Suddenly, Canel faced the prospect of having to find a new home in a market where nearby studios rent for more than his monthly Social Security benefits — his sole means of support.

“I feel like I am suffocating,” Canel, 73, said in Spanish. “Every day.”

The threat of displacement and loss of community and routine can take a mental and physical toll. Experts say that’s especially true for seniors, who are perhaps the most vulnerable to California’s rising rents and evictions of any age group, and the fastest growing in the state.

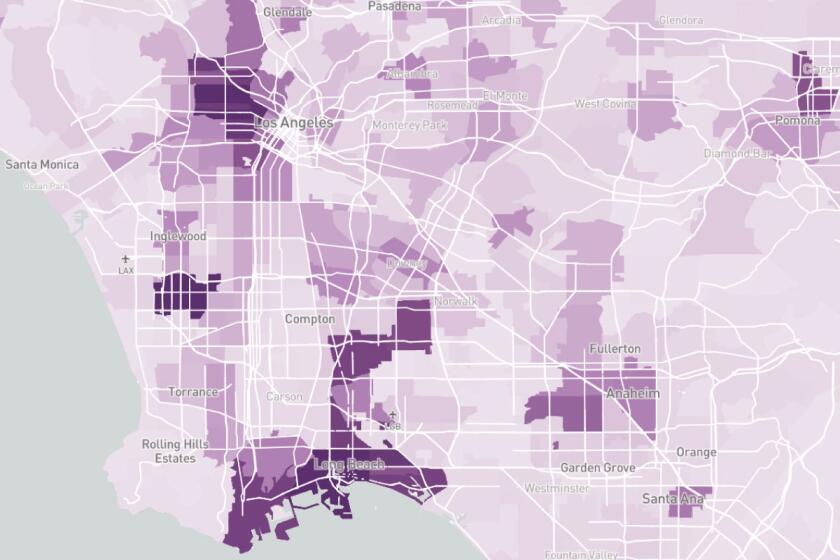

There are signs that seniors are disproportionately affected by the types of evictions Canel now faces. Households with at least one person 62 or older made up 26% of no-fault evictions in Los Angeles city rent-controlled buildings between June 2014 and May 2019, according to the Los Angeles Housing and Community Investment Department. By comparison, 13% of rental households in properties built before 1979 are headed by someone 65 or older, according to 2017 census estimates. (Most rent-controlled buildings in Los Angeles were constructed before 1979.)

The eviction threat was given a face in May when news spread on social media that 102-year-old Thelma Smith faced a lease termination in an unincorporated area of Los Angeles County. Smith had lived at her Ladera Heights residence for nearly 30 years when her landlord gave her notice to leave. Former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, a friend of the woman, was one of many who expressed outrage over the lawful action.

But even when not facing eviction, seniors who depend on a fixed income have a harder time weathering rent increases, even the modest rises allowed under rent control. In 2016, 29% of all renter households in California spent more than half their income on housing, according to the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies. That figure rises to 35% of renters ages 65 to 79, and 42% of renters 80 or older.

Overall rent growth has slowed in the last two years. But the average price for a vacant apartment in L.A. County is nearly 40% higher than it was in 2012, at $2,329 a month, according to Zillow.

That swift rise has been blamed for driving people of all ages into homelessness, but living on the streets can be particularly traumatic for seniors. In 2018, when overall homeless numbers went down, the tally of homeless people 62 and older in the greater Los Angeles area surged 22%, to nearly 5,000. According to the latest count by the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, that number has since increased to 5,231.

Moving is tough at any age, said Tracy Greene Mintz, a senior care consultant based in Redondo Beach. “[But] if you didn’t hear what someone said to you about what [housing] is available, or you can’t read your eviction notice or rental agreement and if you can’t comprehend and problem solve, how are you going to survive that? ... You either adapt to a new routine or you completely fall apart.”

Canel’s new landlord is a limited partnership — a popular real estate investment vehicle. Attempts to reach Stephen Williams, who is listed in a state filing as a representative for the partnership, were unsuccessful. A letter left for Williams at the El Segundo office the partnership lists as its address was not answered and a man there declined to comment. Emails to an address the new owners gave tenants also went unanswered.

Last week, an upstart company started providing furnished apartments for business travelers on Franklin Avenue in Hollywood.

On Bellevue Avenue in Echo Park, a short drive from Canel’s complex, Luis Contreras, 63, and his family are also looking for a new home after another limited partnership purchased their rent-controlled building and gave the tenants an eviction notice. The partnership also lists Williams as a representative.

Contreras, a retired “jack of all trades” who worked in factories and painted houses, has had two open-heart surgeries and said his health is now worsening. But mostly he worries about how his family will find another safe and affordable home on their limited income.

A day after the family of four received notice to leave their $837-a-month, one-bedroom unit, Contreras went to the hospital with chest pains. But he didn’t stay long, despite the advice of the emergency room doctor.

“I’m afraid to leave the apartment unoccupied, because they could come and change the locks,” he said.

Because Contreras is at least 62, city rules allow the family up to a year to move. Kevin Contreras, a security guard in Beverly Hills who is helping his mom, dad and sister search for a new place, said they can afford rent of $1,100 a month. Landlords have told him they won’t accept more than two adults in a one-bedroom; he’s hoping someone will make an exception for his sister, who is disabled. In any case, a recent search on Zillow showed only five one-bedrooms under their price in the entire city of Los Angeles.

Meanwhile, the state is only getting older. The Public Policy Institute of California predicts the number of Californians age 65 and older will grow by more than 4 million come 2030, nearly double what it was in 2012.

In many ways, tenants such as Canel and Contreras who live in rent-controlled buildings have more protections than others. Landlords for those properties, which in the city of Los Angeles were generally built before 1979, can raise their rent by only a limited amount each year and tenants generally can’t be evicted unless they fail to pay the rent or break other rules.

Property owners, however, can charge as much as they want each time a unit is vacated. And, under a state law known as the Ellis Act, they can get rid of rule-following tenants if they permanently remove units from the rental market — something that is often done in order to convert units to condos or build new, more expensive housing.

Tenants removed that way get additional leave and relocation assistance, though that money can be eaten up relatively quickly by moving costs and today’s sky-high rents.

Canel, for instance, can receive a year to move and $21,200. If he were approved for the cheapest place in Silver Lake that’s advertised on Zillow — a $1,225 studio apartment — that would cover the difference between his old and new rents for two years, not taking into account moving costs and a deposit.

In non-rent-controlled buildings, landlords can raise the rent as high as they want and can usually tell long-term tenants to leave in 60 days, as long as doing so wouldn’t break a lease. In those cases, relocation fees are not typically required.

A possible relief valve — subsidized senior housing and Section 8 federal vouchers — is in short supply, forcing people to tough it out in the open market. “On a fixed income, there is just no way you can keep up with changing market rates,” said Steven Wallace, associate director of the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research.

The high proportion of seniors in no-fault evictions may reflect that many have stayed in their units for decades and their low-rent units make their properties especially attractive for redevelopment.

As with so many aspects of the housing crisis, the crunch for seniors is most obvious in gentrifying neighborhoods. Rents in Silver Lake and Echo Park have soared as those and other longtime working-class Latino communities near downtown have seen an influx of wealthier residents.

Pricier restaurants and bars moved in, catering to a clientele who will pay $16 for a bowl of chickpeas and poached eggs.

“There are a lot of white people moving in” who can afford more in rent, said Dora Obando, who moved in next to Canel 25 years ago. Obando, who is in her 70s and also got an eviction notice, feels the Latino community is now being pushed out of the neighborhood.

“We live in such a peaceful environment,” she said, referring to her complex. “For them to not have any mercy and want to evict us feels very unfair to us.”

Richard Green, director of the USC Lusk Center for Real Estate, said gentrification was being driven by supply and demand. Higher-income individuals increasingly want to live in urban centers. An underlying shortage of housing kicks off a chain reaction, pricing middle-class households out of wealthier areas and forcing those people to seek homes in more affordable neighborhoods.

Seeing an increase in demand, Green said, landlords in low-income areas raise rents or redevelop their properties to make more money and cater to wealthier individuals.

Fidela Villasano’s entire world was upending.

But Tracy Jeanne Rosenthal of the L.A. Tenants Union says that view glosses over the role investors can play in kick-starting and accelerating the process by, for instance, marketing an area as “hip.” The union, which is working with the Echo Park and Silver Lake tenants, says government should pass strict rules against speculative investments made to replace one demographic group for another.

Fred Sutton, vice president of public affairs with the California Apartment Assn., said the industry group encouraged its members to think about the “social impacts as they review the operational realities” of their buildings. But he says some old housing needs to be replaced. Rather than control rents, he encouraged cities to expand housing supply and provide direct rent subsidies to those most at risk.

There are ways to cushion the blow of relocation, said Nicholas Castle, a professor at West Virginia University and senior-care expert. In addition to finding a place and moving, seniors need help adapting to a new routine, meeting neighbors and finding the nearest supermarket or church.

Tenants like Canel don’t get that level of help, but a housing department spokeswoman said a relocation consultant can provide people with listings that fit their criteria and transportation to view the rentals.

Then there are the complexities of navigating any assistance program.

You either adapt to a new routine or you completely fall apart.

— Tracy Green Mintz, national senior care consultant

Canel said the local Social Security office told him his $806-a-month low-income benefits, known as SSI, would be cut off if he accepted the relocation payment. That would leave him with only $145 a month in retirement income.

A Social Security spokesperson says SSI could be affected because — unlike retirement benefits — it is needs-based and the relocation payment might qualify as income.

That’s disputed, however, by the Los Angeles Housing and Community Investment Department, which said it hadn’t received any complaints about lost benefits. “It would be unreasonable to force tenants to choose between accepting ‘relocation assistance’ and rejecting ‘relocation assistance’ in order not to jeopardize SSI,” a spokeswoman for the Housing Department wrote in an email.

As a growing number of local governments are turning to rent control, including Culver City, Inglewood and unincorporated L.A. County, state officials are exploring more options to protect renters.

A bill in the state Legislature would temporarily cap annual increases at 7% plus inflation in buildings older than 10 years and provide their tenants with “just cause” eviction protections. And Gov. Gavin Newsom is proposing to spend additional money to provide legal assistance to renters.

Meanwhile, others argue the state efforts don’t go far enough.

On a recent Friday, tenants joined L.A. Tenants Union organizers in a march from Pershing Square to the office of Assemblyman Miguel Santiago (D-Los Angeles), who last year didn’t vote on a bill that would have placed some additional restrictions on the Ellis Act. (Santiago’s office said he’s supporting a more modest Ellis bill this year, as well as the 7% rent cap.)

Canel donned a red homemade T-shirt that read “Stop Acta Ellis” and shouted his story into a megaphone as drivers honked support for the marchers.

In an interview, the septuagenarian said he was more upbeat since joining the Tenants Union in a fight to stay in his home. But he acknowledged his panic hadn’t disappeared.

“I have nowhere to go,” he said. “I could die in the streets.”

Times staff writer Sandhya Kambhampati contributed to this report.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.