Column: America’s healthcare system is failing because competition is disappearing

- Share via

[Update, Oct. 13: Gov. Newsom on Sunday signed AB 290, the measure to cap reimbursements to dialysis firms that was aimed at the big chains, DaVita and Fresenius.

[In his signing message, Newsom leveled criticism at the bill’s opponents for threatening to end charity assistance for Californians undergoing dialysis if the bill had been signed. The threat was mde by the American Kidney Foundation, which is largely funded by DaVita and Fresenius. “Charities that purport to impartially provide patient assistance, and the providers that substantially fund these charities, should act in good faith and continue providing assistance to patients,” Newsom wrote.]

The two major afflictions besetting the U.S. healthcare system are that its prices are too high, and that although big spending should give us better quality of care, it doesn’t.

These two conditions arise from the same cause: American healthcare is becoming less competitive. Hospital chains are growing larger, and within some specialties, providers have become more concentrated.

The result is that Americans get the worst of all possible worlds. Only two conditions can keep prices in check--competition, or regulation. The utility sector is monopolistic, but also price-regulated. As American healthcare becomes increasingly monopolistic, the absence of utility-style price controls means the sky’s the limit.

The late healthcare economist Uwe Reinhardt, and his colleagues saw the consequences clearly in his seminal paper on the fundamental malady of our system. It was titled, “It’s the Prices, Stupid.”

A front group for big dialysis firms threatens to pull out of California if Newsom signs a bill limiting their profits.

Lack of oversight result not only in higher prices, but lower quality. As a new study of the dialysis industry asserts, the acquisition of thousands of dialysis centers by major commercial firms resulted in higher hospitalization and mortality rates of patients and less access to kidney transplants.

“For-profit acquirers’ explicit mandate to maximize profits may lead them to sacrifice patient outcomes,” says the study, prepared by a team from Duke University on a grant from the National Science Foundation.

Their peer-reviewed paper is scheduled to be published by Harvard’s Quarterly Journal of Economics in an upcoming issue. The firms say the study is based on old data and outdated practices, and fails to acknowledge overall improvements in the health of dialysis patients over the years.

When big hospitals merge, the merger partners’ mantra is almost always the same: The deal will deliver lower costs to the lucky patients, with no sacrifice in quality.

The Duke study is based on data from 1998 through 2010. The cutoff point was chosen because the reimbursement system of Medicare, the principal payer for dialysis, changed in 2011 — a change largely dictated by alleged financial abuses by dialysis centers.

That change and other improvements in standards and technology “make the historic data in this study not reflective of the current state of care,” Brad Puffer, a spokesman for Fresenius Medical Care, one of the two major commercial dialysis providers in the U.S., told me. The research team says it’s continuing its work to cover the post-2011 period.

In a prepared statement, DaVita Kidney Care, the second major provider, said it has “improved clinical outcomes for over 20 years.” The firm pointed to a 2010 study in a peer-reviewed medical journal that showed improved patient mortality after two years in clinics acquired by the firm in 2005. The study was co-written by five DaVita executives and used internal DaVita data.

Denver-based DaVita and the German conglomerate Fresenius own or operate more than 5,000 dialysis clinics in the U.S., accounting for more than 60% of the U.S. locations, and collect roughly 90% of the sector’s revenues. During the period under study, they acquired 1,200 formerly independent dialysis facilities.

For-profit acquirers’ explicit mandate to maximize profits may lead them to sacrifice patient outcomes.

— Paul J. Eliason, et al., in dialysis industry study

Increasing healthcare concentration and its consequences are beginning to face closer scrutiny in California. A San Francisco state court jury is scheduled to start hearing testimony this week in lawsuits alleging that the sprawling Sutter Health hospital chain ruthlessly exploited its regional dominance to fix prices. (A case brought by several Northern California employers and another filed by Atty. Gen. Xavier Becerra were combined for the trial.) Sutter is technically a nonprofit provider, but that doesn’t mean its management lacks incentives to maximize the chain’s income.

As for the dialysis industry, healthcare reformers have tried for years to rein in the profits enjoyed by the commercial dialysis industry.

The worst maladies of the American healthcare system are related to corporate profits: The competition among insurance companies to avoid the sickest customers and extract the most money from the rest, and the rise of for-profit healthcare providers.

A California ballot measure that would have capped their profits failed in 2018 after one of the most expensive ballot campaigns in history — about $130 million in total spending, including $100 million in opposition funding contributed by the two big dialysis firms alone. A bill that would cap insurance reimbursements for dialysis passed the Legislature this year and is awaiting a decision by Gov. Gavin Newsom.

The Sutter and dialysis situations raise somewhat different issues. The Sutter case is in the mainstream of antitrust law. It turns on the question of how the chain profited from its position in a regional market. (Sutter’s defense is that the prices in its contracts with insurers and other payers reflect conditions that have nothing to do with its market dominance.)

The roll-up of independent dialysis centers by the two big firms doesn’t have the same effect on regional markets, the Duke study acknowledges. Dialysis centers are typically too small, even in the aggregate, to fall within traditional antitrust law.

“Any individual facility is not going to move market concentration,” says Ryan C. McDevitt, an associate professor at Duke and one of the paper’s authors. He says that it would be more relevant to examine the concentration of the dialysis industry on a national scale.

The dialysis firms point to government statistics showing that overall mortality among dialysis patients has declined by nearly 30% from 2001 to 2016. (The rate is adjusted for the increasing age of the patients.) But that’s not necessarily inconsistent with a rise in mortality among patients at dialysis centers that have transitioned to chain ownership, McDevitt says.

Big companies don’t normally invest tens of millions of dollars with the expectation of losing.

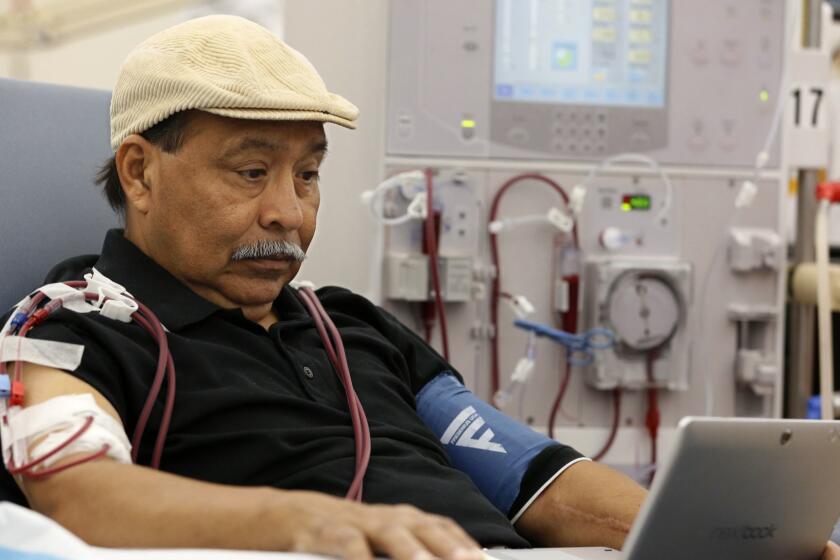

Dialysis, which uses a machine to filter waste products from the blood when a patient’s kidneys can no longer do that job, has long been a special case among medical procedures. Patients typically undergo the hours-long procedure three times a week at a specialized clinic, although home dialysis is gradually becoming more common. It’s generally the only procedure that can keep patients alive until and unless they can secure a kidney transplant, for which waiting lists can be years long.

Because dialysis costs about $90,000 a year, renal patients used to be uninsurable. In 1973, Congress made those patients eligible for Medicare at any age. The procedure soon ranked among the program’s largest annual expenditures and Epogen (EPO), an anti-anemia drug needed by the patients, became Medicare’s largest single annual prescription expenditure.

Under the Affordable Care Act, however, private insurers could no longer refuse to cover kidney patients. DaVita and Fresenius have acknowledged that they profited from the change, because private insurers pay them as much as five times as much per treatment as the roughly $260 paid by Medicare. DaVita, for example, reported last year that while commercial insurers covered only 10% of the firm’s patients, they provided about 30% of its income.

One other change in this system is notable. Through 2010, Medicare paid only about $128 per dialysis session but covered injectable drugs separately. That led to accusations that dialysis providers were gaming the drug reimbursements by discarding partially filled containers instead of using up the contents, so they could charge Medicare for the additional vials. In 2015, DaVita agreed to pay up to $495 million to settle allegations that it inflated prescription billings to Medicare by “creating unnecessary waste.”

A front group for big dialysis firms threatens to pull out of California if Newsom signs a bill limiting their profits.

The company didn’t admit to the allegations, but the settlement was so large that it reduced DaVita’s annual profit by more than half. In announcing the settlement, federal prosecutors observed that after Medicare changed its reimbursement system in 2011 to bundle dialysis treatments and the drugs into a single payment of $260 per treatment, “wastage derived from single-use vials was no longer profitable, and, as a result, DaVita allegedly changed its practices and reduced its drug wastage dramatically.”

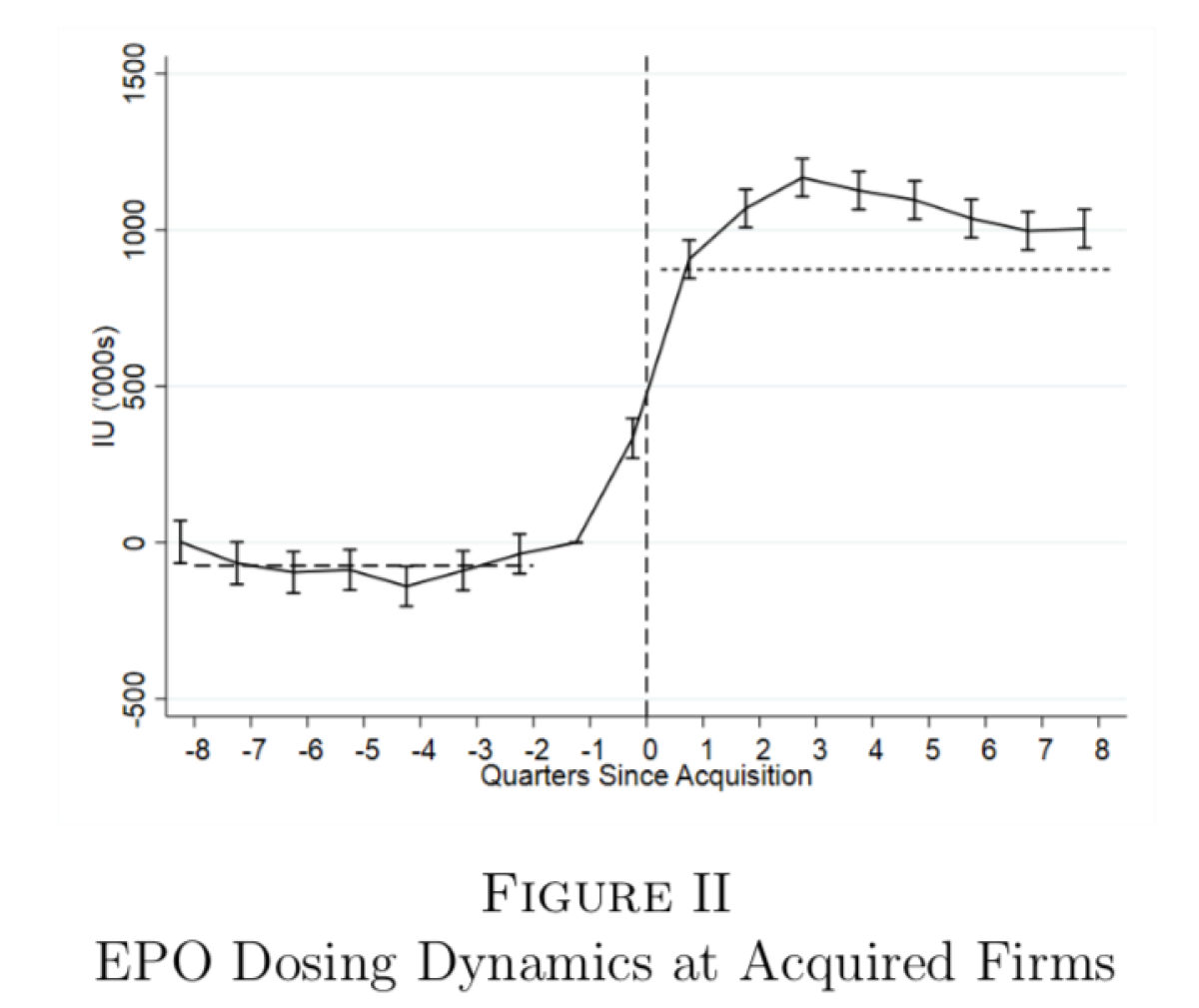

The Duke study appears to document a sharp increase in drug usage at dialysis centers acquired by big chains prior to 2011. “Perhaps reflecting the profits at stake,” the study says, EPO doses more than doubled at independent dialysis centers after they were acquired. DaVita says that drug prescriptions were dictated by physicians, not the firm. But those physicians typically were paid by the firms, and the whistleblower complaint that led to the 2015 settlement alleged that DaVita corporate protocols dictated how dosages were to be drawn from individual vials and ampules to maximize billings.

What’s most telling about the study is its conclusions about how the policies and protocols of the acquiring companies infiltrate the formerly independent dialysis centers they acquire. Using patient-level data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (with the patients’ names kept confidential), the researchers found that patients at acquired facilities were 4.2% more likely to be hospitalized in a given month, while their survival rates fell by as much as 2.9%.

New patients who start dialysis at an acquired center were 8.5% less likely to receive a kidney transplant or be placed on a transplant waiting list during their first year of dialysis.

That was a “reflection of worse care,” the study says, “because transplants provide both a better quality of life and a longer life expectancy than dialysis.”

The study found that acquired facilities tended to have fewer nurses and more “less-skilled technicians,” and treated more patients per employee, “stretching resources and potentially reducing the quality of care received by patients.”

The study’s findings match some earlier research into changes in dialysis centers’ ownership. A 2014 survey of the kidney transplant landscape, for example, found that patients at facilities owned by for-profit chains were 13% less likely to be enrolled in transplant waiting lists, compared to those in facilities run by nonprofit chains.

“For-profit ownership of dialysis chain facilities appears to be a significant impediment to access to renal transplants,” the study concluded, but it could only conjecture about the reasons. The authors speculated that publicly-traded dialysis firms might be wary of referring patients for kidney transplants because ending their need for dialysis would result in “removing a constant stream of revenue from their facility.”

It’s true that great strides have been made in the quality of life and survivability of patients facing the burden of renal disease and dialysis. But much of the improvement can be attributed to the government’s role in the field and its incentives to control costs and improve outcomes. Some of its innovations in payment, for instance, were aimed at reducing the incentives of for-profit providers to extract greater revenues regardless of the health of their patients.

DaVita in its statement attributes improvements in its dialysis results to its “large-scale clinical investments,” including “investments that standardize clinical and infection control practices, support staff training and improve IT infrastructures.” The question is whether the for-profit dialysis industry would have undertaken these investments on its own, or it had to be pushed to do so by government pressure. The profit motive in American healthcare is still as troublesome as it ever was.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.