Column: UC contracts with Catholic hospitals allow religious limits on medical staff, students

- Share via

Religious restrictions on healthcare have been developing into a public health crisis of the first order. New disclosures show how deeply these restrictions have infiltrated an institution that should be a bulwark against them: the University of California.

Clinical and educational training contracts with Catholic hospital chains have placed religion-based constraints on UC personnel and students at every one of UC’s six medical schools, as well as some nursing, nurse practitioner, physician assistant and pharmacy programs.

The contracts remain in force at medical and professional schools at UC San Francisco, UCLA, and UC Davis, San Diego and Riverside. At UC Irvine, a 2016 contract with Providence St. Joseph Health expired at the end of May.

The [Directives] are problematic because they’re not based on science, or medical evidence, or the values and obligations of the university as a public entity.

— UC Regents Chair John A. Pérez

Most of the contracts are with the Catholic hospital chain Dignity Health. The contracts typically require UC personnel and student trainees to comply with Catholic Church strictures on healthcare while practicing or doing field training at Dignity facilities. The restrictions don’t apply when UC personnel and students are working or studying at UC facilities such as its own medical centers or clinical sites not operated by Dignity.

In some cases the restrictions could prohibit UC personnel at Dignity facilities from even counseling patients about medical options that conflict with church doctrine, such as contraception and abortion. UCSF also has training agreements with Providence St. Joseph in Oregon and Washington state.

The most restrictive church rules are specified by the Ethical and Religious Directives on Catholic Health Care, known as the ERDs, a document issued by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops that bars almost all abortions, sterilization procedures such as tubal ligations, and provision of contraceptives. The directives are in place at many of the hospitals named in the UC contracts, even though UC is prohibited by the state Constitution from allowing religious considerations to govern its operations.

The contracts were obtained by the ACLU of Northern California via a Public Records Act request. The documents raise new questions about whether UCSF officials were candid with university regents in testimony this spring over a proposed affiliation between UCSF and Dignity Health. UCSF abandoned the plan in May in the face of a public uproar and professional rebellion at the school.

The University of California regents are wrestling with a question that should have an easy answer: Should they approve an “affiliation” between UC San Francisco, one of the leading teaching hospitals in America, and Dignity Health, a Catholic hospital chain that openly discriminates against women and LGBTQ patients and requires its doctors to comply with religious directives, some of which run counter to medical science and ethical practice?

In defending the proposal, UCSF officials suggested that UC providers would be able to circumvent many of the religious strictures by transferring patients to hospitals with less restrictive rules, and sometimes through subterfuges such as falsifying patient records.

But as the ACLU observed in a Nov. 15 letter to UCSF officials, “even at the time of these assertions, UCSF ... already had entered into contracts with Dignity Health that explicitly tie the hands of UC providers and require them to comply with Dignity Health’s religious doctrine.” (Emphasis in the original.)

“They argued that there was some sort of bubble privilege around UCSF providers operating in these religiously restrictive facilities giving them greater latitude to provide evidence-based care to their patients,” says Phyllida Burlingame, reproductive justice and gender equity director at the Northern California ACLU.

But an educational training contract reached last year and effective through August 2020 shows that the UCSF providers are “specifically tied to the Ethical and Religious Directives [at Dignity] facilities.”

UC President Janet Napolitano’s office told me by email that “there is no contract that we read as restricting our personnel’s ability to counsel, prescribe or refer according to the standard of care and their professional judgment.”

After the furor over the UCSF proposal, Napolitano established an 18-member working group of faculty and administrators from across the system to establish guidelines for future collaborations with outside health systems whose values may not conform to UC’s.

The group is expected to make its report around the end of this year. UC refused to provide a full list of the group’s members.

The ACLU is calling for the termination of any contracts that “impose religious restrictions on care.” University officials say they’re “in the process of drafting amendments” to active contracts, but haven’t disclosed the language.

In a campuswide message issued Friday, UCSF Chancellor Sam Hawgood and UCSF Health Chief Executive Mark Laret — both of whom are members of the working group — said they expect that UCSF personnel, wherever they’re working, “will always practice medicine and make clinical decisions consistent with their professional judgment and considering the needs and wishes of each patient.”

That’s a dodge. The problem is restrictions on procedures and treatments that UC providers would prescribe for patients, but that can’t be performed for patients at Catholic facilities.

Declaring that President Trump’s rationale for his antiabortion “conscience” rule had no basis in fact, a judge throws it out.

“Even if UC providers are permitted to make clinical decisions ‘consistent with their professional judgment,’” cautions Vanessa Jacoby, an associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive science at UCSF, a leading critic of its Dignity proposal and another member of the working group, “the inability to carry out these clinical decisions because treatment is prohibited by religious directives forces UC providers to adhere to the ERDs.”

Any attempt to accept religious judgments on healthcare in future contracts might well run into a buzzsaw at the UC Board of Regents. “The ERDs are problematic,” says board Chairman John A. Pérez, a former Assembly speaker, “because they’re not based on science, or medical evidence, or the values and obligations of the university as a public entity.”

Pérez, who spoke out against the UCSF-Dignity proposal last spring, said he would “have a difficult time agreeing to any renewal of agreements if they maintain ERDs and other measures that are inconsistent with UC policies and medical standards of care.”

Dignity, for its part, claims that it and UC “have always expected any physician practicing at a Dignity Health location to discuss all treatment options, prescribe appropriate medications, and facilitate access to another provider if a Dignity Health location does not provide a desired service.”

That’s another dodge, since under the ERDs Dignity hospitals don’t stock contraceptives even if they’re prescribed by a physician and have to be administered in a clinical setting, and the directives further bar employees from even making referrals for abortions. Transferring a patient to another hospital may not measure up to the standard of care if the patient needs immediate treatment that the Dignity location won’t provide because of the bishops’ rules.

Most of the contracts obtained by the ACLU apply to clinical training programs conducted at the sectarian hospitals for students in medicine, nursing or pharmacy. But the pacts also include a UCLA contract for emergency services and a UCSF contract for cardiology services.

Some of the contracts covering training programs give the hospitals the right to request the ejection of faculty members or students deemed to have violated the religious rules, based on the “sole judgment” of the hospital.

No cases have yet emerged of faculty or students removed from programs for violating the church rules. But two lawsuits are pending in California state courts asserting discriminatory treatment by Dignity hospitals acting in compliance with the directives.

One was brought by a patient whose hysterectomy was abruptly canceled when hospital administrators learned he was transgender, and the other by a patient who was refused a tubal ligation that was to be performed in conjunction with a Caesarean delivery, even though performing both procedures at the same time is standard medical practice to protect the health of the patient.

It’s impossible to overstate how drastically these contracts depart from California law and public policy. The state Constitution explicitly dictates that the university “shall be entirely independent of all political or sectarian influence ... in the administration of its affairs.” The Constitution warns against discrimination on the basis of “race, religion, ethnic heritage or sex.”

UC San Francisco announced Tuesday that it is dropping plans for an expanded affiliation with Dignity Health, a Catholic hospital chain that places flagrantly discriminatory restrictions on abortions, transgender care and other services.

California also has been at the forefront of the battle against the imposition of religious limitations on healthcare. Just Tuesday, in a lawsuit brought by the state, San Francisco and Santa Clara County, federal Judge William Alsup of San Francisco blocked President Trump’s so-called conscience order, which vastly expanded the rights of doctors, nurses, even ambulance drivers and hospital receptionists to refuse to participate in procedures such as abortions by claiming moral objections. (On Nov. 6, a New York federal judge, ruling on other lawsuits, also blocked the order.)

In the California cases, the state and its fellow plaintiffs had called Trump’s rule a “coercive ‘gun to the head’” that would force hospitals, other healthcare providers and their patients to “adhere to the religious beliefs and practices of every employee.”

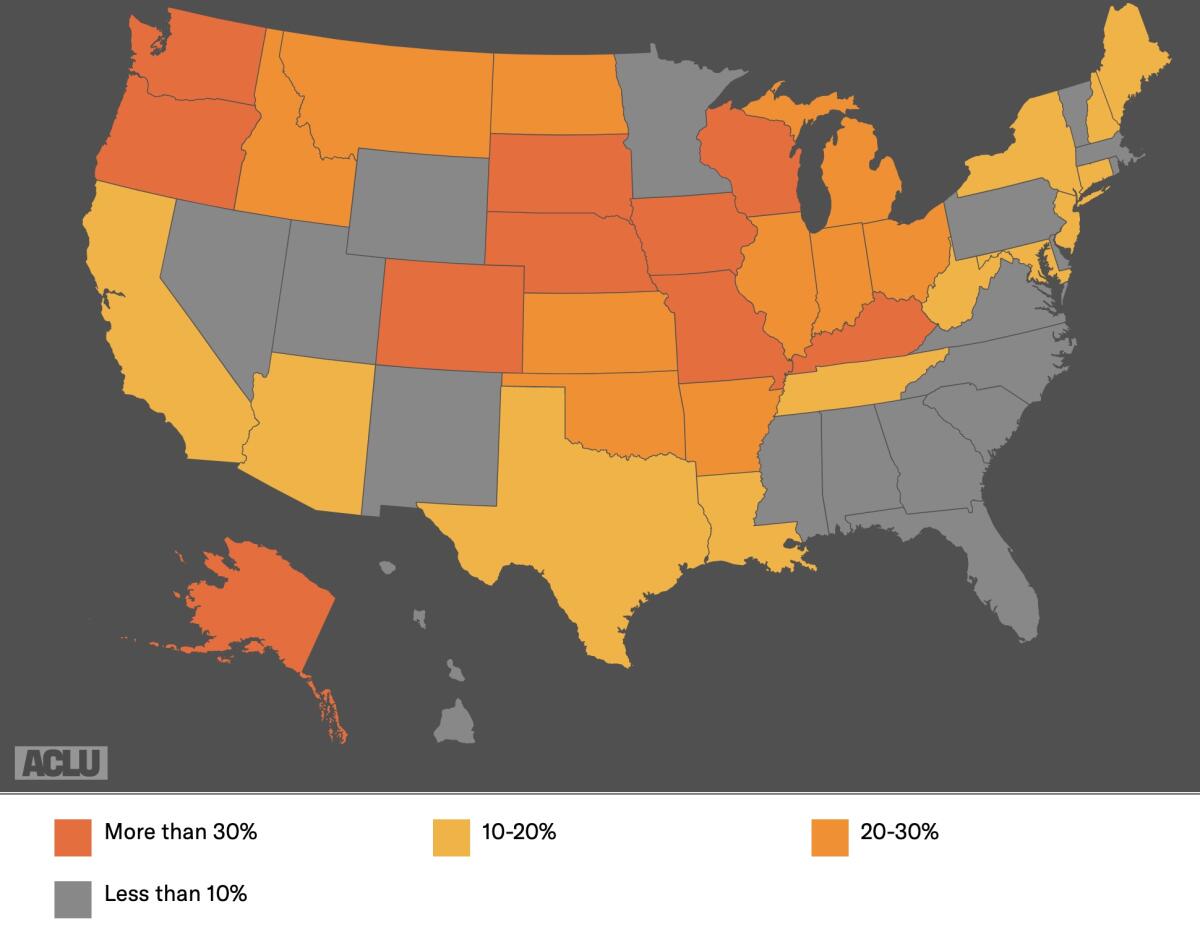

Catholic Church restrictions on medical practice have increasingly become an issue nationwide as Catholic hospitals expand their footprint coast to coast through acquisitions and affiliations, reaching the point where 1 in 6 U.S. hospital beds is subject to the church directives. Dignity is now the fifth-largest hospital chain in the country and the largest not-for-profit system in California.

Officials at many of the UC campuses assert they have little choice but to forge clinical and teaching partnerships with Dignity facilities because of their own space constraints. “Even with UC’s scale, access to our care at UC facilities is limited by capacity and geography,” Jacqueline Carr, a spokeswoman for UC San Diego, told me by email. “Relationships with other healthcare organizations allow us to care for more patients ... and provide training to tomorrow’s health professionals.”

Concerns about religious restrictions on care helped to block a big hospital merger in California.

Yet the contracts provide for no departure from practice limitations derived from the ERDs or the church’s Statement of Common Values, a slightly less restrictive document in force at some Dignity facilities.

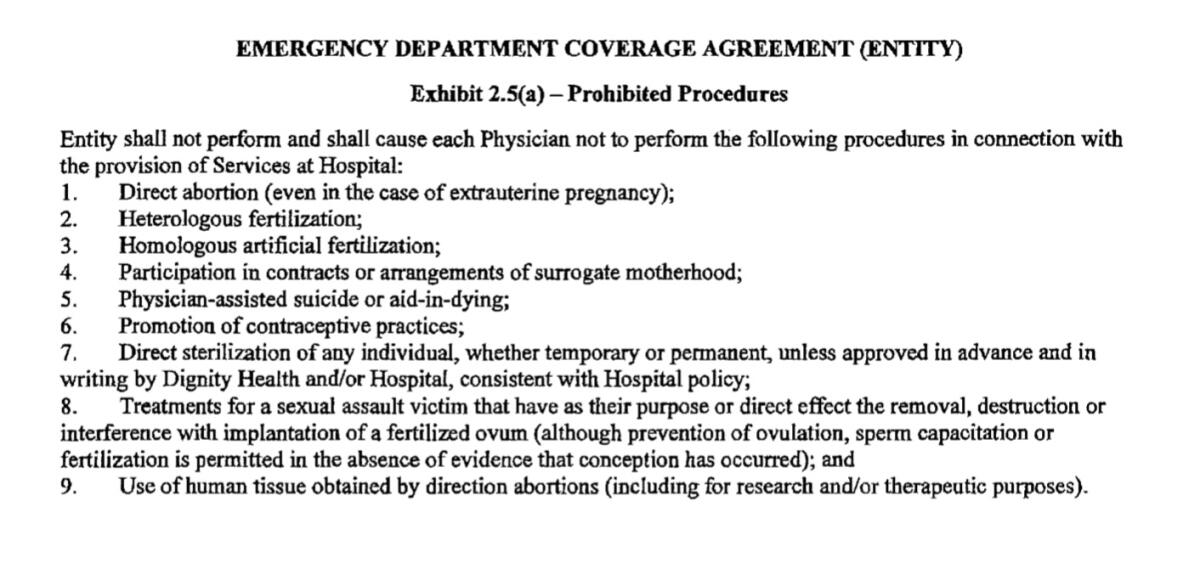

A February 2019 contract through which UCLA physicians provide emergency services at Dignity’s California Hospital Medical Center in downtown Los Angeles, for example, specifies nine “prohibited procedures,” including abortions, even for medically dangerous extrauterine pregnancies; physician-assisted suicide or “aid in dying”; “promotion of contraceptive practices”; and treatments for victims of sexual assault that aim at the “removal, destruction or interference with implantation” of a fertilized egg.

The ERDs go further than merely prohibiting certain procedures. The directives dictate that in “any kind of collaboration, whatever comes under the control of the Catholic institution — whether by acquisition, governance, or management — must be operated in full accord with the moral teaching of the Catholic Church, including these Directives.”

They forbid administrators and employees to “manage, carry out, assist in carrying out, make its facilities available for, make referrals for, or benefit from the revenue generated by immoral procedures” such as abortions and sterilizations.

In other words, by collaborating with Dignity and other Catholic institutions, UC is making itself complicit with much broader constraints on the ability of its professionals and students to serve themselves and their patients in accordance with science- and medicine-based healthcare. Those are the values that the University of California must stand up for, uncompromisingly.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.