Column: COVID-19 may make universal basic income more palatable. That’s a good thing

- Share via

The idea of a universal basic income — a regular stipend paid to every American adult to meet minimum life needs — has been bubbling around the edges of American politics for decades.

With the coming of the coronavirus pandemic, UBI may finally move to center stage, and stay there.

“This is a moment when the UBI idea is possibly going to feel more appealing to a lot of people,” observes Ioana Marinescu, a labor economist at the University of Pennsylvania who has studied what she calls unconditional cash transfer programs.

‘COVID-19 has created a rare policy window where so many people are now tangibly feeling the economic insecurity we’ve been talking about.’

— Sukhi Sharma, director, Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration

UBI had gained currency during the early stages of the current election cycle thanks to the efforts of Andrew Yang, who made the idea the centerpiece of his run for the Democratic nomination for president until he suspended his campaign Feb. 11. Since then he has been promoting the idea via a nonprofit, Humanity Forward.

“Universal basic income is a lot more popular now than it was even several months ago, because of the clear need in our communities,” Yang told me. The near-universal experience of receiving $1,200 checks as coronavirus rescue payments has strengthened the appeal of the idea, he says.

“They liked it,” he says. “They didn’t find that it transformed their work ethic or made them into lazy wastrels. So there’s a lot of experience that puts to bed a lot of the resistance that people had.”

If there’s one thing that many anti-poverty activists and free-market advocates agree on, it’s that our existing social safety net isn’t capable of dealing with the challenges presented by the evolution of the economy and of the very definition of work.

The hope of many fans of UBI is that the coronavirus crisis, by exposing the gaping inequities in America’s economic structure as the Great Depression did in the 1930s, will usher in a New Deal-like social revolution.

That would be beneficial to millions of Americans who have been marginalized by diminishing educational and employment opportunities. But it’s wise to keep in mind that powerful entrenched political interests will strive to keep the present structure in place, despite the pandemic.

As I’ve mentioned in the past, the concept of universal basic income has long enthralled political and social thinkers across the ideological spectrum as diverse as Huey Long, Milton Friedman, Martin Luther King and Richard Nixon.

They’re not all interested for the same reasons. Conservatives such as political scientist Charles Murray are intrigued by the possibility of replacing existing safety net programs wholesale, presumably at lower cost.

Progressives wish to use UBI to patch holes in the safety net and the labor market opened by the modern workplace, such as the growth of gig work without guaranteed hours or pay.

Definitions of UBI vary: Some involve phase-outs by income, though typically at higher income levels than existing safety net programs; some direct the money to specific population segments such as single mothers, though that makes them not universal at all; and many differ over the amount of income judged to be “basic” or even whether the payments should be enough for recipients to live on without any other income.

Employers’ gratitude for their ‘hero’ workers didn’t last long

The canonical UBI program would provide at least $12,000 a year per adult — the level advocated by Yang. That would cost an estimated $3 trillion a year, or about two-thirds of current federal annual outlays. The tax increases needed to cover that bill will mobilize political opposition.

The program would have to be truly universal to remove the stigma attached to means-tested programs such as food stamps. A check would go to everyone, whether they’re employed or not. No strings attached. No means test. No bureaucrats examining your personal lifestyle or looking for hidden income. No politicians demanding that you seek out even a menial job or leave the children in the hands of caretakers before getting the money.

The payments would not phase out with rising income to eliminate what conservatives decry as the “poverty trap” — when more income means the loss of benefits, they posit, recipients are encouraged to stay out of the labor pool. (Reducing the handout to higher-income households could be done through progressive taxation.)

That’s roughly the structure of what may be the highest-profile UBI experiment in the nation: The Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration, or SEED. Funded by foundations and private donors, SEED began providing $500 monthly stipends to 125 households randomly selected from among neighborhoods in the California city with household incomes below the city median.

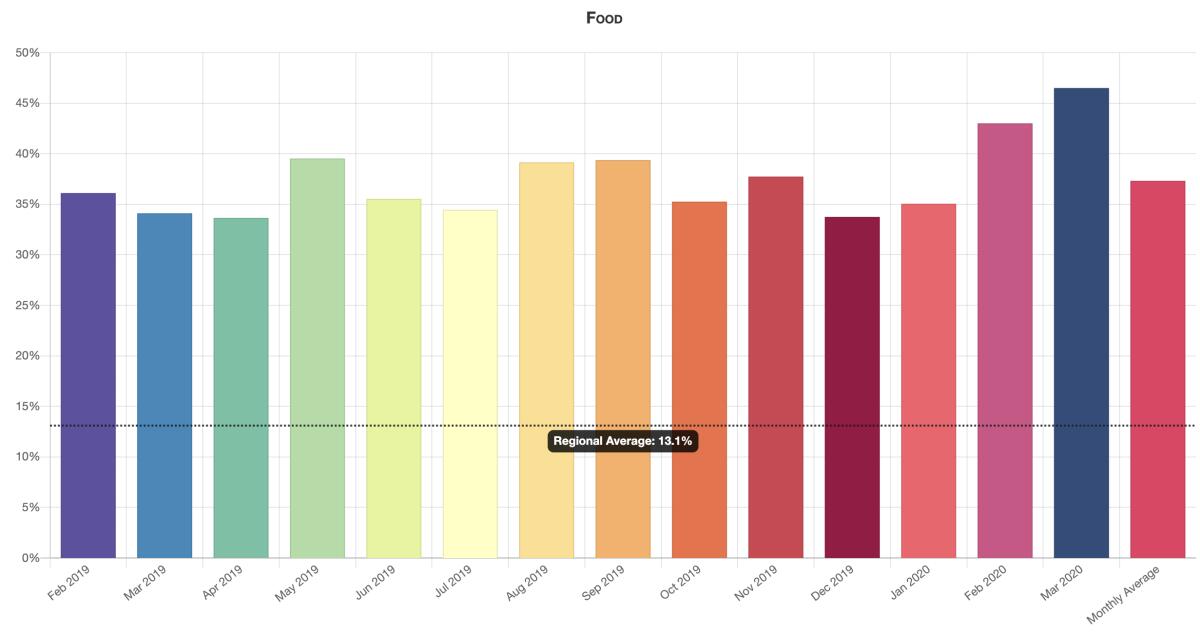

The recipients’ median monthly household income was $1,800, so the $500 amounted to a significant income bump of nearly 30%. About 37% of the households are Hispanic, 28% black and 11% Asian. The program began in February 2019 and will run until July, though its organizers are trying to raise funds to continue for a further six months.

The project has helped to explode numerous misconceptions about how recipients would spend unconditional windfalls — that they would binge on nonessentials or abandon work, for instance.

“People are first and foremost spending money on necessities —food shelter, utilities, etc.,” says Stockton Mayor Michael Tubbs, an organizer of the project. “There also are recipients using that money to better their economic circumstances, whether it’s to go back to school, pay off debt, to take time off work so they can apply for a full-time job.”

As the pandemic emerged, according to program data, recipients stepped up their purchases of food, to 46.5% of total spending in March from 34% a year earlier.

“That shows how widespread the issue of food insecurity is in our community and society at large,” Tubbs says, “but also that people are making decisions rooted in how best to provide for their family needs.”

Those findings resemble those from other examples of unconditional cash programs, such as Alaska’s Permanent Fund Dividend, paid out of the state’s petroleum extraction fees, and tribal dividends from Indian casinos: The money typically is not spent wastefully, but tends to improve social metrics such as education and children’s health.

The U.S. is suffering shutdown fatigue because the COVID-19 war has stagnated.

The most important effect the coronavirus crisis may have on public opinion of UBI is the prevailing rationale. In the past, UBI has been seen largely as a remedy for automation-related job losses.

“This is sometimes presented as ‘The Robots Are Coming,’” Jesse Rothstein, a former chief economist at the U.S. Department of Labor now at UC Berkeley, wrote last year with his Berkeley colleague Hilary W. Hoynes.

The coronavirus crisis has shifted the thinking more toward the idea as a response to the inadequacy of America’s economic safety net.

“The U.S. has a social welfare system that is pretty limited,” says Pennsylvania’s Marinescu. “All the rescue packages that have already been passed are a demonstration of that. They had to enact a whole bunch of new bills in order to deal with the fallout because the system we have wasn’t able to deal with it.”

The stimulus cash payment of $1,200 per adult incorporated in last month’s CARES Act “could be seen as a very short-run UBI, which 90% of Americans got without any conditions,” Marinescu says.

The pandemic might change the perception of UBI as a program chiefly aimed at the poor or long-term unemployed. “One concern that many people have about UBI is that it goes to people who don’t need it or don’t deserve it,” Marinescu says. “But this crisis has been so visible for everybody and has affected so many people that that’s far less of a concern.”

Indeed, the crisis turned political leaders who in other contexts were skeptics of cash handouts into believers in universal assistance.

One is Sen. Mitt Romney (R-Utah), who decried public assistance benefits as a presidential candidate in 2012 but tweeted in March, as the pandemic was gaining steam, that “every American adult should immediately receive a one-time check for $1,000.”

Whether COVID-19 will give the idea of universal basic income staying power after the crisis passes is hard to gauge.

“There are reasons why we might want to use something that resembles UBI as part of a portfolio of responses to the coronavirus crisis,” says Rothstein. “The CARES was right to think that it was more important to get money out quickly than to get it perfectly targeted” to people most in need.

Rothstein says it may be better to think about “the insight of UBI — that the movement over the last 25 years to tie all of our safety net to work means that we’re leaving out people who really need the help. A movement towards having aid that’s available to people who are unable to work or who are not working is a good move.”

He’s right about that: The coronavirus crisis has shown the folly of tying health benefits to employment at a time when access to healthcare is of paramount importance and jobs are disappearing.

The crisis also has inspired more thinking about how to redress the longer term economic woes of millions of Americans. That’s reflected in a proliferation of proposals from Democrats on Capitol Hill for regular assistance payments at least through the crisis, and in broad public support for continuing the assistance.

“COVID-19 has created a rare policy window where so many people are now tangibly feeling the economic insecurity we’ve been talking about,” says Sukhi Samra, director of the Stockton project. “It has given us a unique opportunity to act and to re-create our system.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.