Column: The government says you can now invest your 401(k) in private equity. Be very afraid

- Share via

Ever on the lookout for new money-making opportunities for the average American, the Trump administration earlier this month cleared the way for 401(k) plans and similar individual accounts to invest in private equity funds.

According to Labor Secretary Eugene Scalia, this reflected President Trump’s determination, via a May 20 executive order, “to remove barriers to the greatest engine of economic prosperity the world has ever known: the innovation, initiative, and drive of the American people.”

That’s some opportunity.

We have seen a number of proposals from private equity funds where the returns are really not calculated in a manner that I would regard as honest.

— Warren Buffett, May 2019

Private equity funds, which invest in companies that aren’t listed on stock exchanges and therefore don’t have to report their finances or operations publicly, are among the riskiest and most opaque investment vehicles devised by Wall Street.

They often saddle the acquired companies with heavy debt, diminishing their long-term prospects even as they produce short-term profits for the promoters. And their capital may be tied up in illiquid investments that make it hard for clients to get their money out when they wish.

Until now, ordinary Americans have been effectively barred from the sector because of a requirement of the Securities and Exchange Commission that they be open only to “accredited” investors — generally those with at least $200,000 in income in recent years or net worth of at least $1 million, not including a home.

On June 3, however, the Department of Labor issued guidelines allowing sponsors of 401(k)-style plans to offer investments with a private-equity “component.”

Trump’s evisceration of labor protections will continue under Labor Department nominee Scalia

The agency did place some restrictions on how those investments must be structured. Direct investments in private equity firms by ordinary investors are still prohibited. Instead, the private equity components would have to be nestled within larger diversified funds that have sufficient liquidity to pay off investors who want out right away.

Nevertheless, the change is a big gain for private equity promoters, who have been lobbying for years to get their mitts on the estimated $6.2 trillion in 401(k) accounts and $2.5 trillion in individual retirement accounts. They may hope that once the door is cracked open, some of the remaining restrictions will be whittled away.

Is this sector a good idea for the average 401(k) owner? I don’t normally offer investment advice through this column, so let me put it this way: If I were inclined to invest my 401(k) money in private equity, I would hope that my family would arrange to have my head examined.

Scalia doesn’t see things that way, of course. In his June 3 announcement of the new guidelines, he called the rule change a way to “help Americans saving for retirement gain access to alternative investments that often provide strong returns.”

He said his aim was to “level the playing field for ordinary investors ... to ensure that ordinary people investing for retirement have the opportunities they need for a secure retirement.”

Keep your eye on that word “often.” It’s a common weasel word, the subtext of which is that “alternative investments” often don’t provide strong returns.

It’s proper to observe that Scalia hasn’t distinguished himself as a champion of the rank-and-file worker, which made him the perfect selection to head Trump’s Department of Labor when he was appointed last year.

Just this month, Scalia came out against a Democratic proposal to extend the $600 weekly bump up in federal unemployment benefits past July 1. By then, he said, “the circumstances that originally called for the $600 plus-up will have changed.” That’s debatable, since more than 20 million American remain out of work today.

Private equity funds are known as alternative investments in part because they operate in an alternative reality from traditional investments: They produce limited disclosure, or no useful disclosure at all; there are no commonly accepted formulas to measure their returns; and they’re subject to management fees immensely higher than conventional stock, bond or money market funds.

No less an experienced investor than Warren Buffett warned his own shareholders away from the sector.

“We have seen a number of proposals from private equity funds where the returns are really not calculated in a manner that I would regard as honest,” Buffett said at the May 2019 annual meeting of Berkshire Hathaway, which holds his corporate investment portfolio. “If I were running a pension fund, I would be very careful about what was being offered to me.”

State and local employment collapsed for the second month in a row, raising doubts about a national recovery

Charles Munger, Berkshire’s vice chairman and Buffett’s long-time business partner, added his own observation that private equity firms sometimes juice their reported returns by parking money in treasury bills but not reporting the low-return holdings in their portfolio results. “All they’re doing is lying a little bit to make the money come in,” he said.

The private equity sector’s claim to produce returns superior to those of conventional stocks and bonds has been regularly questioned. Whatever gross returns are enjoyed by private equity firms are eaten away by the fees collected by their promoters, typically 2% a year on total value plus 20% of profits.

As Brett Arends of MarketWatch observes, taking the average gross return of the Standard & Poor’s 500 index at 12% a year (not counting inflation), a private equity fund would have to notch gross returns of 17% a year just to match the S&P 500. That’s unrealistic, to say the least.

An analysis of the record written and posted after the Labor Department rule change by Ludovic Phalippou of Oxford University found that the gross returns of private equity funds roughly matched those of public stock indices, but that a disproportionate share of the gains went into the pockets of private equity insiders.

“The number of PE multibillionaires,” he observed, “rose from 3 in 2005 to 22 in 2020, and are mostly affiliated to large PE firms.”

Private equity firms say that they remain popular among big institutional investors, which must mean they offer some legitimate value.

Phalippou doesn’t buy that argument. He attributes their popularity to conflicts of interest among institutional decision makers, and to “low financial literacy among both principals and even many agents —people who policy makers uniformly classify as ‘sophisticated investors.’”

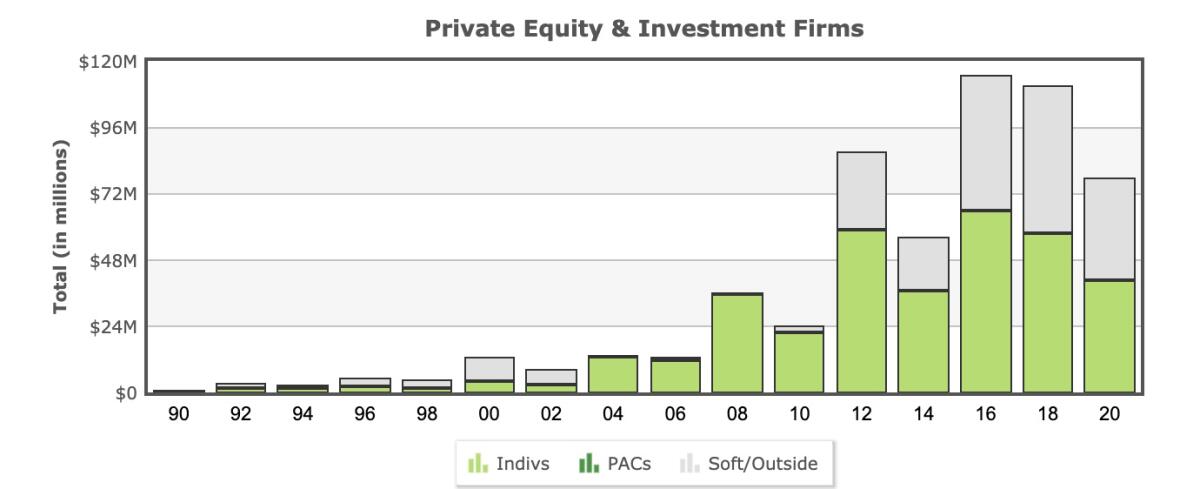

Private equity firms have wriggled their way into the inner circles of the Republican Party and the Trump administration through liberal applications of cold cash and influence. In 2018, the firms made nearly $110 million in contributions to candidates and political action committees, and this year (thus far) about $77 million.

The donations have been roughly evenly split between Republicans and Democrats in the most recent two election cycles.

But the largest private equity firm, Blackstone Group, recently has sent the vast bulk of its contributions to conservative and Republican recipients — about $18.5 million of its $21 million in 2019-2020. Blackstone’s co-founder and chairman, Stephen A. Schwartzman, was a top advisor to President-elect Trump during the 2016 transition.

The spotlight has been focused as never before on two contributing factors in the evolution of local police into quasi-military forces: union contracts that delay and complicate discipline and oversight, and a flood of battlefield equipment provided by the Defense Department to police forces ill-trained to deploy it, but incentivized to use it in communities.

Schwartzman has made no secret of his desire to get his hands on retail investors’ money. “In life you have to have a dream,” he said during a January 2017 conference call with Wall Street analysts.

“One of the dreams is our desire and the market’s need to have more access at retail to alternative asset products. ... At the moment a lot of people are not allowed to put those into retirement vehicles and other types. And one of the interesting issues when you have a new government is whether they want to continue that type of prohibition or not.”

Get the hint, Mr. President? (Kudos to David Sirota for unearthing this priceless nugget.)

To place Schwartzman’s desire in perspective, Eileen Appelbaum of the Center for Economic and Policy Research calculates that just 5% of the funds available from 401(k) and Individual Retirement Accounts would come to $435 billion — “real money even to private equity millionaires and billionaires,” she writes. “The value proposition for workers, whose retirement income will likely be eaten up by fees for returns that may not materialize, is much less clear.”

She’s right. The median 401(k) account doesn’t have enough in it to support its owner through a lengthy retirement.

That’s an argument for keeping a balance of risk and reward in their portfolios, not for taking a flyer in high-risk, questionable reward “alternative investments.”

If the Labor Department of Trump and Scalia were really concerned about the retirement prospects of the rank-and-file, they would warn them away from private equity, not open the doors wider.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.