Column: California is still showing how to make Obamacare work, even with COVID-19

- Share via

Amid the patchwork of state-level approaches to healthcare reform, California has always stood out for its all-in embrace of the Affordable Care Act.

The state expanded Medicaid, taking full advantage of a federal government subsidy of the expanded program’s costs — starting at 100% from 2014 to 2016 and settling at 90% this year and beyond.

It established its own individual insurance exchange, Covered California, and managed it actively so that coverage options and expenses would be understandable for applicants and benefits would be consistent.

This is a story about what it means to be a counterpoint to three years of an administration seeking to undercut the Affordable Care Act, versus a state that says, ‘No, that’s not the track we’re going to take.’

— Peter V. Lee, Covered California

When the Trump administration and Congressional Republicans pursued a strategy of undermining the ACA by cutting marketing budgets and allowing cheap junk insurance plans to flood the market, California resisted.

The state banned junk plans, instituted an individual mandate penalty as a substitute for the penalty the GOP Congress repealed in 2017 and extended premium subsidies further into the middle class than the federal subsidies did.

The result has been continued strong enrollments and comparatively moderate premium increases. More than 418,000 Californians enrolled in Covered California during open enrollment for the first time for 2020, a 41% increase from the year before. The state exchange covers about 1.5 million members.

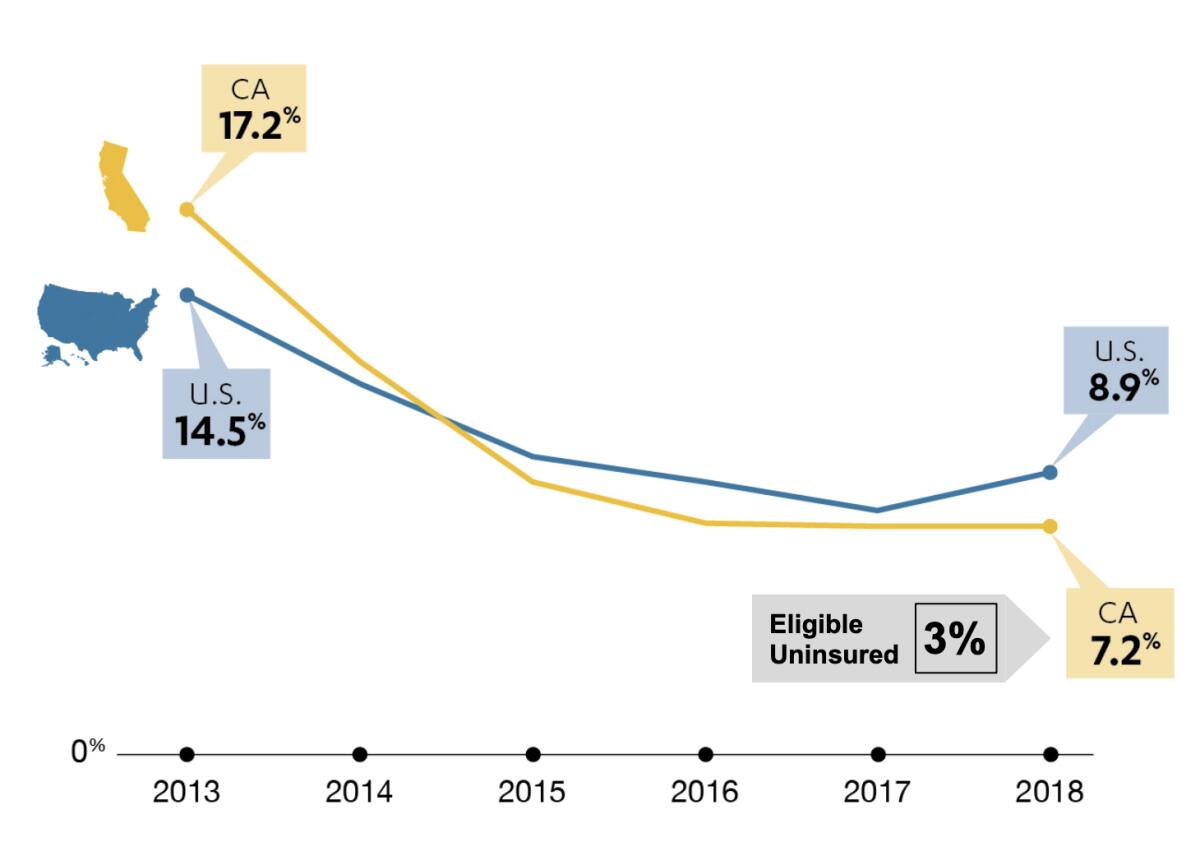

As I reported a few months ago, during that halcyon era before COVID-19 became the nation’s No. 1 concern, since the inauguration of the individual insurance exchanges in 2013, California’s uninsured rate has fallen by 10 percentage points, to 7.2%.

That’s the largest drop in the nation. Among “eligible uninsured” people — that is, excluding those barred from participating because of their immigration status, such as adult undocumented residents — the rate is even lower, 3%.

The question this spring was whether the coronavirus would upend the system Covered California created. The answer appears to be no. Covered California on Tuesday announced that average premiums for 2021 will rise by 0.6% — even lower than the 0.8% increase charged for coverage this year over last.

California’s full-on acceptance of the Affordable Care Act has yielded dividends for the state, its residents and even the federal government.

Customers willing to shop for new 2021 plans, the exchange says, can do even better — reducing their rates by an average of 7.3% statewide and as much as 13.4% in parts of Los Angeles County, without changing their benefits. The figures don’t reflect state and federal subsidies, which can reduce premiums even further.

“This is a story about what it means to be a counterpoint to three years of an administration seeking to undercut the Affordable Care Act, versus a state that says, ‘No, that’s not the track we’re going to take,’” Peter V. Lee, executive director of Covered California, told me. “We’re seeing in California a multiyear payoff of building on the Affordable Care Act.”

The exchange’s experience with COVID-19 costs may well be replicated across the country, for aggregate healthcare costs due to the disease haven’t soared, as many feared when the pandemic emerged in the spring.

Those fears seemed eminently plausible only a few months ago. Covered California issued an analysis in March projecting that the one-year costs in the national commercial insurance market could “range from $34 billion to $251 billion for testing, treatment and care specifically related to COVID-19.”

If insurers had to “recoup 2020 costs, price for the same level of costs next year and protect their solvency,” the exchange warned, premium increases for 2021 for COVID alone “could range from 4% to more than 40%.”

The 11 insurers that sell plans through Covered California initially projected that they might have to bump up premiums by 2% to 5% to cover costs associated with the coronavirus, Lee says.

The exchange gave them an extra month, through mid-July, to submit final premium proposals so they would have a better handle on the potential costs. By then the smoke had cleared, and the projections ranged from zero to about 3%.

All 11 carriers will stay in the exchange next year. Two will expand within the state: Anthem Blue Cross will add five counties, and Oscar will add one.

Several factors contributed to moderating the insurers’ calculations.

One was that efforts such as shelter-at-home policies to limit the spread of COVID-19 in California worked, especially through the spring.

“The scope and scale of hospital admissions is far less than they might have been if California had sat on its hands and let the pandemic run its course,” Lee says. Covered California’s initial estimates were for at least 400,000 COVID-related hospital admissions this year; there have been fewer than half that many.

Although infections are rebounding in California, the overall cost of treatment is declining as medical professionals learn best practices. “Far fewer of the people who are infected are hospitalized, and of those who are hospitalized, fewer end up in intensive care,” Lee says.

Meanwhile, deferrals of non-emergency surgery by patients wary of entering hospitals during the pandemic have exceeded any added costs of COVID for commercial insurers. (The impact on hospitals is another story — some are facing red ink from the dearth of profitable procedures.)

Indications are that elective procedures will rebound through the end of this year, Lee says, but they’ll fall within the insurers’ non-COVID expectations. The exchange was careful to warn, however, that “there continues to be considerable uncertainty about the progress of the pandemic and resulting healthcare service costs.”

Another factor is Covered California’s expansion of its special enrollment period — leaving enrollment open through the end of this month for uninsured Californians.

The Republican proposal on coronavirus relief puts all the risk from catching COVID-19 on workers.

The exchange’s open enrollment period traditionally ends on Jan. 31 for coverage in a calendar year, after which one must have experienced a designated life change — such as loss of job-related coverage, marriage or the birth of a child — to sign up. This year, the pandemic prompted the exchange effectively to extend open enrollment to June 30, then July 31 and, currently, to Aug. 31.

More than 230,000 people have signed up since March 20, the exchange says, more than twice as many as took advantage of the special enrollment period in the same period a year ago. More to the point, those signing up this year have been much healthier on average than those who signed up during the special enrollment period in previous years.

Typically, the exchange says, the special enrollment pool is less healthy than the traditional open enrollment cohort, possibly because many of those who make a point of signing up after they’ve lost job-related coverage or have other life-changing events are relatively more motivated to avoid a lapse of coverage, presumably because they suffer from medical conditions or know their prospects are riskier.

This year, the special enrollment pool resembles the open enrollment group in terms of health risks. That’s good for insurers, because healthier enrollees effectively subsidize sicker members.

Some non-COVID factors contributed to the moderate premium increase for next year, Covered California says. One is the Congressional repeal last December of the ACA’s health insurer tax, which goes into effect Jan. 1.

This tax, which ranged as high as 3.3% of collected premiums, was thoroughly detested by the insurance industry, which finally got its way on a permanent repeal after goading Congress to suspend it in 2017-2019. The repeal lowered premiums for 2021 by about 1.7% on average, the exchange says.

Still, the most important lesson from Covered California’s experience with rates is that expanding the pool of insured individuals and families by making sure that coverage is indeed affordable is the key to making the ACA work.

Trump continually asserts that the ACA has been a “disaster” and promises that he’ll sign a replacement reform that always seems to be two weeks over the horizon. But he doesn’t have any ideas for doing so, and no answer for the reality that California has made the ACA work.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.