Can Prop. 16 boost California’s Latino-, Black-, Asian- and women-owned companies?

- Share via

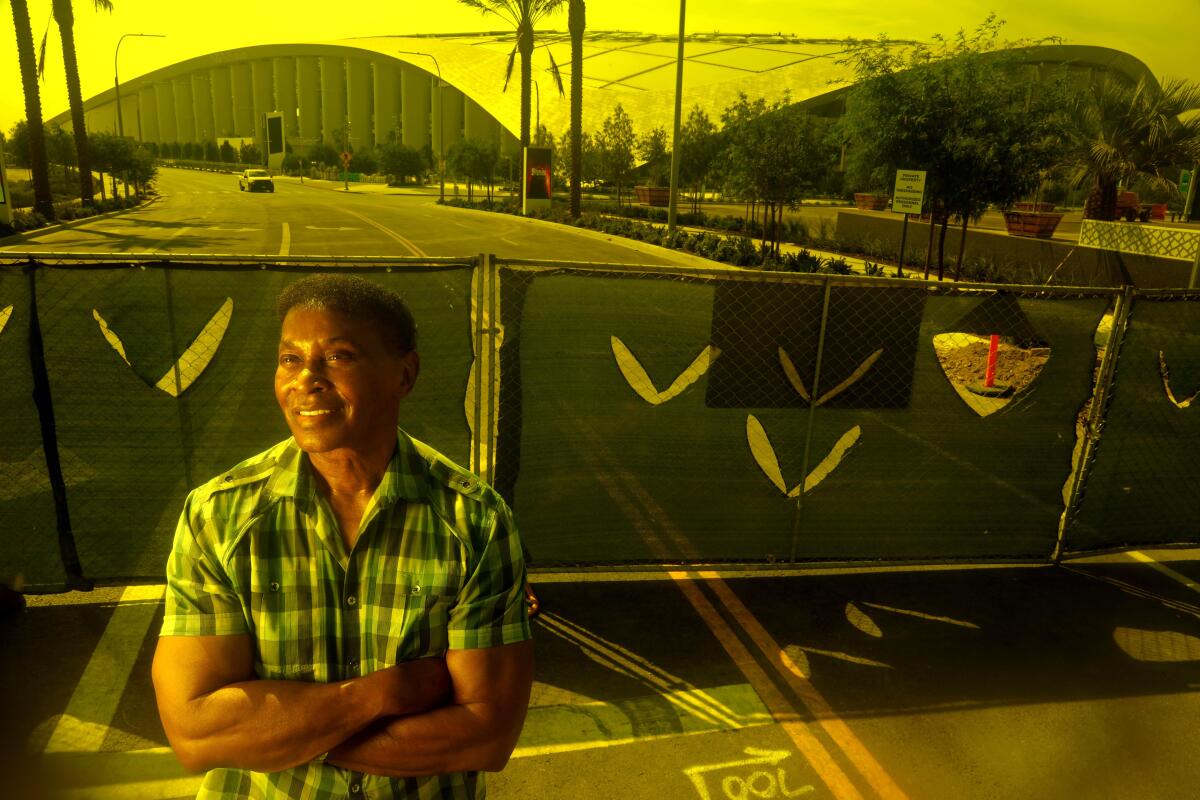

Twenty-five years ago, Gene Hale, president of a Gardena construction company, was selling more than $8 million a year in cranes, forklifts and concrete to help build freeways from San Diego to Sacramento.

But in 1996, when Californians approved Proposition 209, outlawing affirmative action for Black-owned companies like his, “that wrecked procurement with the state,” he said. Hale’s business with public agencies, which accounted for about 10% of his revenue, “basically went down to zero.”

A quarter century later, California, the first of several states to bar race- and gender-based programs, is one of the first to revisit the issue. An initiative on the November ballot, Proposition 16, would repeal the 1996 measure.

The proposed turnabout comes as debates over racial and gender equity have exploded nationwide in the wake of police violence against Black and Latino people and sexual harassment scandals at the highest levels of business and government.

Opponents of Proposition 16 say promoting diversity should not involve racial and gender preferences: The state should be colorblind and gender-blind — whether in the realm of public university admissions or of businesses seeking to tap into the multibillion-dollar state procurement system.

In practice, affirmative action in contracting never completely disappeared in California. Under U.S. law, federally funded projects such as highways continued to allow the targeting of “disadvantaged enterprises,” defined as Latino-, Black-, Asian- and women-owned businesses.

But Proposition 16 could lead to reinstating extensive state and local programs to encourage racial and gender equity. Proponents calculate that Black-, Latino-, Asian- and women-owned businesses — including many small companies, such as Hale’s — have lost out on hundreds of millions of dollars in state-sponsored contracting opportunities over the last two decades.

The loss of state programs “was devastating to our communities,” said Hale, who serves as chairman of the Greater Los Angeles African American Chamber of Commerce.

This year’s measure doesn’t propose new language. It would simply erase the section of the California constitution that now reads: “The state shall not discriminate against, or grant preferential treatment to, any individual or group on the basis of race, sex, color, ethnicity, or national origin in the operation of public employment, public education, or public contracting.”

Polls suggest Proposition 16 could lose, overshadowed by a slew of more controversial initiatives on this year’s ballot.

And those who remember Proposition 209 are more likely to recall the debate around admissions to public universities than its effects on state and local contracting.

But partly because of its impact on the state’s economic landscape, the measure has broad business support. The state Chamber of Commerce, which had remained neutral on Proposition 209, is a backer, as are Gov. Gavin Newsom and vice presidential candidate Sen. Kamala Harris.

In the last quarter century, the state has become more racially diverse. Today, 39.4% of Californians are Latino, followed by 36.5% non-Hispanic white, 15.5% Asian and 6.5% Black. Four percent identify as multiracial, and smaller percentages identify as Native American or Pacific Islander.

Beneath the fury over George Floyd’s death lie longstanding economic inequities that have plagued California’s 2.6 million black people.

“We’ve had 24 years of failure because of Prop. 209,” said state Sen. Steven Bradford (D-Gardena). Overturning the 1996 measure “affords us the opportunity ... to remove the barriers of hiring, the barriers of education, remove the barriers of opportunity.”

But Ward Connerly, a Black Republican businessman who spearheaded Proposition 209, has returned to defend it as head of the campaign against Proposition 16.

“Every time you give someone affirmative action, you’re discriminating against somebody else,” he told a San Diego television station. “In order to build a civil society, everyone needs to believe they will be treated equally and fairly by their government.”

When it comes to economic opportunity, the complex regulations and often opaque finances of public agencies seem designed to confuse the average voter. But the money at stake in Proposition 16 is massive.

Public procurement involves a vast swath of the California economy — everything from infrastructure at the ports of Los Angeles, Long Beach and Oakland to prison laundries and courthouse janitorial services. The state, with an overall budget of $321 billion, issued 624,569 contracts to private businesses last year, but does not publicly tally the full dollar amount.

City and county governments award thousands of contracts too. Los Angeles alone spent about $4 billion last year, with the city’s utility, the Department of Water and Power, and its airport authority among the biggest contracting agencies, according to Mayor Eric Garcetti’s office. The city’s Department of Public Works — which builds libraries, fire and police stations, sidewalks and sewage plants—doled out $290 million to private companies last year.

Affirmative action has given many entrepreneurs a toehold as they were getting started.

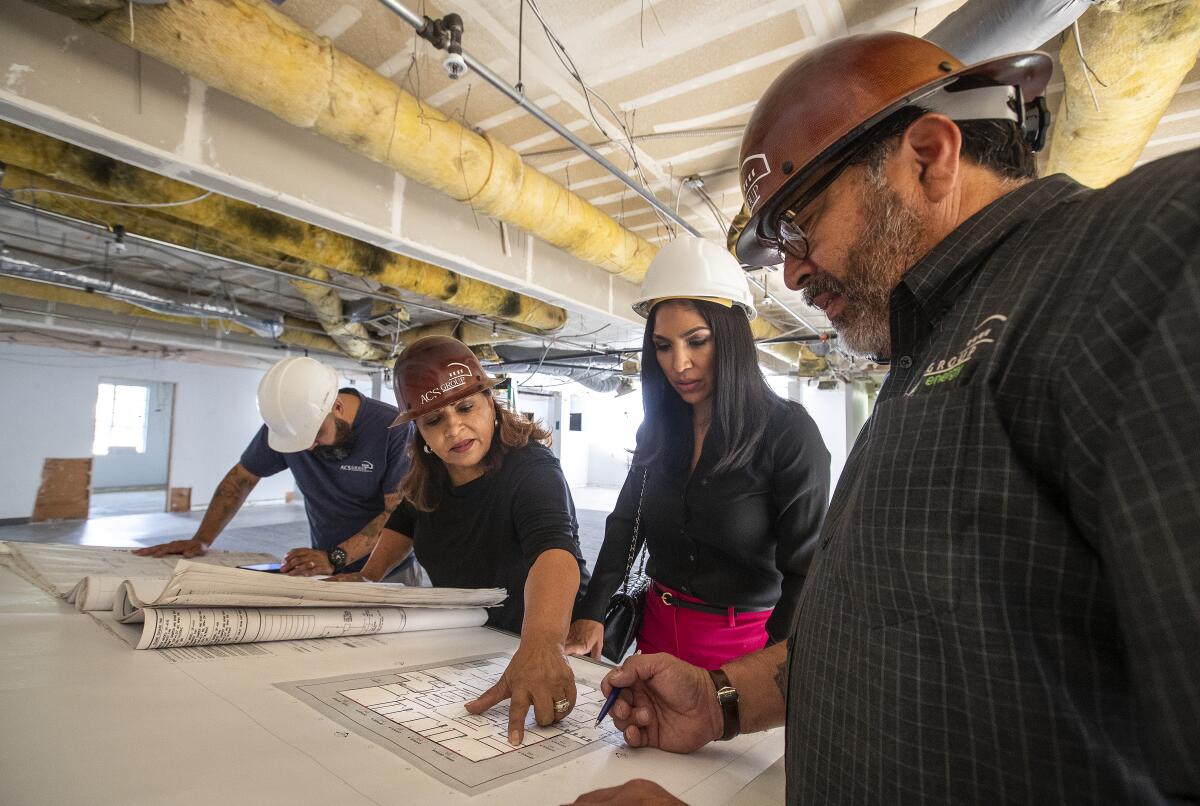

“In the late 1980s, I took advantage of affirmative action because there was such disparity,” said Anna Sauceda, who with her husband, Darrel, owns ACS Group, a Santa Fe Springs construction firm. “It was an opportunity to get in there and compete. We were able to build our résumé.”

The Saucedas, who are Mexican American, said that more than half their firm’s annual revenue of $4 million to $10 million comes from public contracts. They built a 4.5-mile walkway for the city of Whittier and installed lighting and Wi-Fi in Lynwood parks. Their business-to-business contracts include one for $2 million to weatherize homes for Southern California Gas Co.

“Prop. 16 would level the playing field so you can build new people into the system,” said Darrel Sauceda, who is chair of the Los Angeles Latino Chamber of Commerce. General contractors often rely on “the good-old-boy network” to find subcontractors, he added. “Prop. 16 will mandate they start using fresh horses.”

In placing Proposition 16 on the ballot, the legislature asserted in a preamble: “In the wake of Proposition 209, California saw stark workforce diversity reductions for people of color and women in public contracting and in public education.”

But exactly how much Latino-, Black-, Asian- and women-owned businesses have suffered from the loss of state-sponsored affirmative action is unclear from public records. Many California agencies stopped collecting comprehensive race and gender-related data.

Five years ago, a study commissioned by the Equal Justice Society, an Oakland-based nonprofit, cited the 24.5% of the state’s 1995 contracts awarded under its now-disbanded program for “minority- and women-owned business enterprises.” The study calculated, in inflation-adjusted dollars, that Proposition 209 cost those companies $825 million a year.

Similarly, lawsuits forcing San Francisco and San Jose to abandon their affirmative action programs in the wake of Proposition 209’s passage resulted in losses for minority- and women-owned businesses of $30 million and $20 million a year, respectively, the study suggested.

The Californians for Equal Rights Campaign, the anti-Proposition 16 organization, calls the study’s numbers “not actually losses, but taxpayer dollars saved by avoiding preferential treatment.”

The group also cites a 2007 UC Santa Cruz study that found the cost of state-funded highway contracts fell 5.6% after affirmative action was halted, due perhaps to “higher costs of firms located in high-minority areas.”

But current public data do not track what has happened to the hundreds of millions of dollars a year that used to be routed to businesses led by women and people of color. Most of that money presumably isn’t returned to taxpayers but, rather, is spent on contracts with other firms.

Last month, the University of California, which spends $12 billion a year on contracts for goods and services, released a report on Proposition 209 that found “the implications for UC’s diverse suppliers were acute.”

Before affirmative action was outlawed, 10.2% of UC’s spending went to “disadvantaged business enterprises,” which include Black-, Latino- and Asian-owned companies, and 5.7% to firms owned by women.

Those numbers dropped to 2.79% and 1.85%, respectively, by fiscal 2019, according to the report.

Lost in the contentious debate is the fact that federally funded projects still require “good faith” outreach to suppliers based on market studies that set race- and gender-based numerical goals.

The California Department of Transportation reports that nearly a fifth of the $10.8 billion it spent on federally funded projects over the last five years went to certified “disadvantaged business enterprises,” which include Latino-, Black-, Asian- and women-owned companies.

At the same time, contracts for purely state-funded roads — $7.8 billion over the same period — were not covered by any race- or gender-based outreach rules given that CalTrans’ “minority- and women-owned business enterprise” goals were disbanded in 1997.

Large city public works must also take affirmative action if they get federal funds. As a result, Los Angeles’ 6th Street Viaduct project is directing 24% of its $340 million in construction contracts to Black-, Latino-, Asian- and women-owned businesses.

For projects without federal funding — say, a new police station — Los Angeles adheres to Proposition 209 by requiring contractors to reach out not only to suppliers who register as “minority” or “women-owned” in the city’s database, but also to white-owned businesses.

“Contractors have to cast as wide a net as possible and tell us what their goals are,” said Greg Good, president of the city’s Public Works board. “They literally have to show us they’ve made the phone calls” to suppliers.

“But Prop. 209 casts a heavy shadow,” he added. “We can’t make the participation of minority businesses or women-owned businesses part of the scoring criteria” in awarding a project.

If Proposition 16 passes, city affirmative action programs could mimic federal rules by studying diversity in various trades and setting numerical expectations for outreach to suppliers.

“Structural racism is real,” Good said. “Los Angeles is a giant economic engine, and we can play a big role in ameliorating that.”

Even if affirmative action were to be restored, however, it would continue to rely not on quotas but on governments holding contractors to “good faith” efforts to expand their usual suppliers to new Latino, Black, Asian and women-owned businesses.

Those efforts can fall short.

“Public agencies call it ‘good faith,’” said Lola Smallwood Cuevas, co-founder of the Los Angeles Black Worker Center, a nonprofit advocacy group. “We call it ‘good fake.’ The operative word is ‘ask.’ You can ask contractors for an inclusionary workforce. Some volunteer, and others may not.”

Several years ago, Cuevas was part of a coalition that met with companies bidding on the $2-billion Crenshaw/LAX light-rail line. “You ask, ‘How do we ensure Black workers are on a project?’ The first thing they say is, ‘Prop. 209 doesn’t allow us to speak specifically about the Black community.’”

Hale, the Gardena construction firm owner, said general contractors for public agencies “can just pretend to make a good-faith effort. All they have to do is offer proof that they made some phone calls to minority subcontractors.”

For the moment, he is busy selling equipment for the construction of SoFi Stadium in Inglewood and for a hotel near the Los Angeles Convention Center. But he looks forward to an era of more robust affirmative action, whether in this election cycle or another.

“Aspirational goals don’t get you much,” he said.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.