Column: With Biden’s election, Democrats expanded their grip on the productive economy

- Share via

By some measures, Joe Biden won the presidential election by a relatively narrow margin, drawing down-ticket Democratic candidates along in a fairly weak wake.

Biden and the Democrats, however, convincingly solidified their commanding lead in a key metric: victory in the nation’s most economically important regions.

That’s the inescapable conclusion to be drawn by mapping Biden’s electoral strength against contributions to national gross domestic product, by county.

Biden flipped half of the 10 most economically significant counties Trump won in 2016.

— Mark Muro and colleagues, Brookings Institution

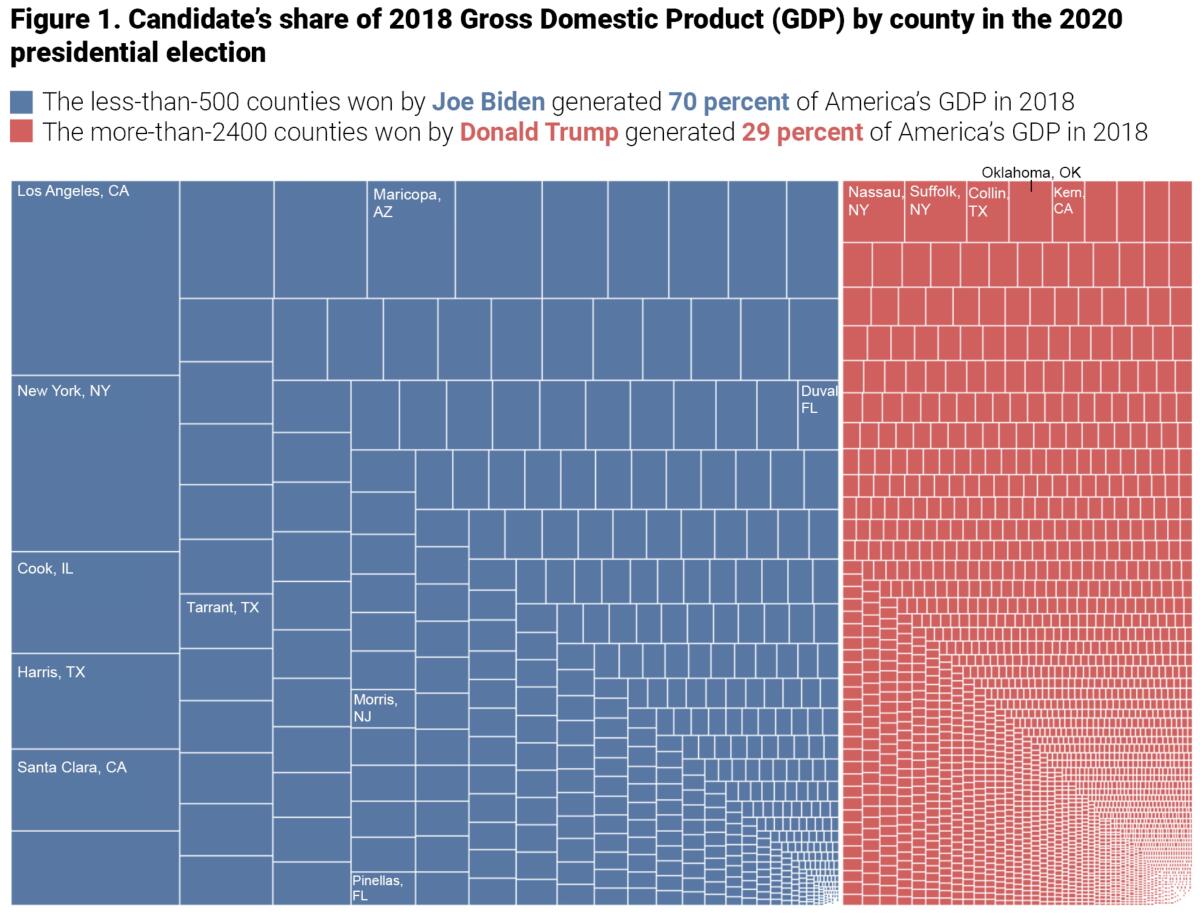

According to Mark Muro and his colleagues at the Brookings Institution, who did the mapping, the 477 counties that Biden won produced 70% of U.S. GDP in 2018, leaving the rest to the 2,497 counties won by President Trump.

The productivity divide isn’t between layabouts and hard workers, but between the traditional economy and the new: in the simplest terms, between agriculture and legacy manufacturing oriented toward durable hardware on the one hand, and high-technology and professional occupations on the other.

These distinctions tend to be reflected, if imperfectly, in geography. The old economy is rural and small-town, the new is metropolitan and cosmopolitan.

“The GOP simply does not have significant ties to many large-output places,” Muro told me.

Trump won only six of the 100 most productive counties in terms of their contribution to GDP, he noted. Among them was California’s Kern County, which ranks high in GDP output because of oil production. But as a fossil energy producer, Kern is part of the old economy rather than the new.

Biden’s victory outdid the record of Hillary Clinton in the 2016 election. Clinton’s 472 counties contributed 64% of GDP (in 2014), while Trump’s 2,584 counties contributed only 36%. In other words, the nation’s economic divide is even more stark now than it was four years ago.

“Biden flipped half of the 10 most economically significant counties Trump won in 2016, including Phoenix’s Maricopa County; Dallas-Fort Worth’s Tarrant County; Jacksonville, Fla.’s Duval County; Morris County in New Jersey; and Tampa-St. Petersburg, Fla.’s Pinellas County,” Muro et al wrote.

This isn’t merely a postelection parlor game. The nation’s economic geography points to sharply divergent policy needs.

Biden wants more infrastructure and safety net investment. Trump wants to cut taxes. Which will aid the economy more?

Voters in the Democratic economic centers, the Brookings team observes, “tend to prioritize housing affordability, an improved social safety net, transportation infrastructure, and racial justice.” Their jobs “also disproportionately rely on national R&D investment, technology leadership, and services exports.”

Such concerns seem either irrelevant or inimical to the interests of Trump county residents. When your entire community is struggling to make ends meet, building metropolitan infrastructure or helping discrete groups raise themselves up by their bootstraps don’t rank high among policy demands.

Free trade principles, which are favored by new-economy participants, look like threats to steal jobs from old-economy workforces.

“On the urban side of the line, the economy is information-driven, skills-oriented and growing faster than the countryside,” Muro says. “That economy is competing well globally, with services exports growing rapidly. So there’s a greater comfort level in these places with where the economy is headed.”

California reflects this national-level divergence in microcosm, though the divide is starker than in the nation as a whole. Brookings’ data show that Trump counties in California — 23 of the state’s 58 counties — account for only 5% of the state’s GDP. That’s mostly due to Kern, which alone accounts for 2%. Biden added Butte and Inyo counties to the 33 won by Hillary Clinton in 2016 for his projected win of 35 counties.

Although California’s general prosperity “mitigates some of the worst tensions, there are clearly geographical and economic tensions in the state,” Muro says — blue California is concentrated along the coast and the Bay Area, hives of information-based industry, while the state’s interior, home to agriculture and energy production, is still very much red.

In 2016, Trump rode this economic divide to electoral map victory. As I wrote in September, Trump built his strategy that year around a direct appeal to voters in the industrial and agricultural heartland, particularly through an overt attack on globalization.

Whether he could ride the same strategy to victory four years later was always in doubt, largely because he failed to deliver on his promises to rebuild the old economy in its traditional self-image.

Manufacturing did not recover — Trump papered over its continued stagnation with lies, as when he claimed at a rally in Saginaw, Mich., to have “brought you a lot of car plants” while in reality only one new auto assembly plant had been announced in the entire state during Trump’s term. Auto and auto parts manufacturing had actually shrunk even before the pandemic.

Trump’s economic vision looks to a long-gone America; Biden’s to the next stage.

Trump’s trade war, which he claimed to have waged on behalf of traditional manufacturing, failed to deliver measurable gains and imposed heavy costs on agriculture in regions that had become dependent on produce exports, especially to China.

Those failings may have helped to drive Biden’s flip of more economically important counties from Trump, though the residual strength of Trump and the Republican Party in the old-economy regions remains visible in the 2020 results.

The economic map of the 2020 vote illustrates shortcomings of policy and messaging by Democrats that should concern the party as it contemplates the future.

Democrats still are not addressing rural and small-town concerns. They seem to accept the transformative motion of the American economy toward service and high-tech industries, and the outflow of manufacturing jobs to other lands offering cheap labor without developing a program to bring an equivalent transformation to Americans left behind.

“We have two economically and geographically based parties that are talking past each other and inhabit different political bases,” Muro says. “It’s not a picture of likely success for growing the economy.”

Along with his Brookings colleagues Robert D. Atkinson and Jacob Whiton, Muro has proposed a federal investment program targeted at left-behind regions that show a determination to become new-economy growth centers. Their idea is to invest $100 billion over 10 years in 10 communities that would compete for the infusion.

The funding would comprise up to $700 million a year in research and development investment in each metro area for 10 years, along with tax and regulatory relief, business financing and infrastructure spending, among other things.

“Many Americans now reside far from the opportunities associated with the nation’s innovation centers, undercutting economic inclusion and raising social justice issues,” the Brookings authors wrote.

Building up new innovation centers would relieve social strains in the existing centers such as mushrooming housing prices and traffic congestion. In effect, such a program would spread the benefits of new-economy growth more broadly into the white working class.

“Democrats have to speak to these people,” Ruy Teixeira, a political analyst who has tracked the demographic changes contributing to Democratic strength in recent decades, told Greg Sargent of the Washington Post just before election day. “They haven’t been doing well for decades. Their communities have suffered declines, jobs problems, healthcare problems.”

Just because they’re disgruntled and voting Republican doesn’t mean their concerns should be dismissed. “You don’t need a message that will only appeal to the Rust Belt or only appeal to the Sun Belt,” Teixeira said. “You can run on a broad message that has appeal not only to persuadable members of the white working class in the Northern-tier swing states, but also has appeal to those voters in Southern states, to younger voters, to nonwhites all over the country.”

America’s economic divide presents a great opportunity for Biden to make good on his commitment to bringing the nation together. Defeating the politics of hate-mongering and resentment that Trump exploited to divide Americans has to start by recognizing that America is already divided along an economic line, and Job 1 has to be eradicating that line, for everybody’s good.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.