Column: Dietary supplements are largely unregulated. That’s just dumb

- Share via

Whatever else we’ve learned from the race to come up with a COVID-19 vaccine, it’s clear that consumers depend on federal authorities to make sure the medicines we take are safe and effective.

So why do those same authorities all but shrug off the safety and effectiveness of dietary supplements — those over-the-counter herbal and holistic remedies intended to address potentially serious ailments?

These products are sold without any requirement for upfront evidence of effectiveness and without a need for regulatory approval prior to being offered to consumers.

While many if not most supplements are benign and pose no apparent health threat to the public, the largely free rein given to the $35-billion industry creates an unwelcome opportunity for unscrupulous businesspeople to indulge their worst tendencies.

Case in point: Checks worth a total of nearly $775,000 are currently being mailed to more than 13,000 consumers nationwide as part of a settlement between the Federal Trade Commission and a Colorado supplements company called AS Research.

The settlement involves a supplement called Synovia, intended to relieve arthritis and joint pain.

The FTC found that AS Research “made misleading health claims” and “used phony testimonials, including one in which a user said he gave away his walker” after using Synovia.

The complaint says there’s no truth to AS Research’s claims that Synovia is “clinically proven” to significantly reduce arthritis pain and restore damaged cartilage.

It also says AS Research tried to get customers to upgrade to an enhanced version of Synovia for an extra $9.95 beyond the standard cost of nearly $70, including shipping, for a one-month supply.

“In fact,” the complaint says, “Defendants ship the same product to all consumers, whether or not they pay an additional $9.95 per bottle.”

An FTC spokesman told me about 10% of the Synovia settlement cash is going to California residents.

No one at AS Research responded to my requests for comment. The settlement says the owners of the company “neither admit nor deny any of the allegations” against them.

The practices described by the FTC are obviously skeevy. But we’ve seen a number of similar instances in recent years, and especially since the outset of the pandemic.

In one such case, I wrote in April about the FTC cracking down on a Los Angeles businessman named Marc Ching, whose company, Whole Leaf Organics, sold a supplement called Thrive that purportedly “treats, prevents or reduces the risk of COVID-19.”

The company “represented that the benefits of Thrive are clinically or scientifically proven,” the FTC’s complaint says. “In fact, there is no competent and reliable scientific evidence that Thrive or any of its ingredients treats, prevents or reduces the risk of COVID-19.”

A Los Angeles Times investigation subsequently found that Ching allegedly engaged in troubling practices involving pet-related businesses and an animal-rescue charity.

The questionable supplements sold by both AS Research and Whole Leaf Organics could have been stopped in their tracks if the Food and Drug Administration required supplement makers to meet safety and efficacy requirements similar to those for makers of prescription drugs.

Pharmaceuticals have to undergo multiple tests and trials before they’re approved for use by consumers. The process typically takes years, although the urgency of finding a COVID vaccine accelerated things in a big way.

Supplements, on the other hand, are largely unregulated prior to hitting store shelves.

“Manufacturers and distributors of dietary supplements are responsible for ensuring that their products are safe and lawful, well-manufactured and properly labeled, and the FDA is authorized to take action when it identifies a violation,” said Courtney Rhodes, a spokeswoman for the agency.

In other words, the FDA will weigh in only after a problem arises. The FTC, for its part, focuses on potentially deceptive marketing practices, which, again, typically come to light only after a product goes on sale.

“Currently, the FDA has no systematic way of knowing what dietary supplement products are on the market, when new products are introduced or what they contain,” Rhodes acknowledged.

The FDA has proposed strengthening its oversight of supplements, but Congress has shown no interest in giving it that power.

That’s clearly not good enough, as recent crackdowns demonstrate.

Daniel Fabricant, chief executive of the Natural Products Assn., a trade group representing the supplements industry, told me there’s no need for supplements to be overseen as rigorously as prescription drugs.

“They look like drugs, but they’re not drugs,” he said. “That’s like saying we should put orange juice through clinical trials to make sure it contains vitamin C.”

Yeah, no.

Federal law says companies can’t claim a supplement will cure an illness but they can say a supplement may be good for addressing certain conditions. For example, you can’t say melatonin will cure insomnia but you can say it may help you get to sleep.

The problem is that, in the eyes of at least some consumers, this may be a distinction without a difference.

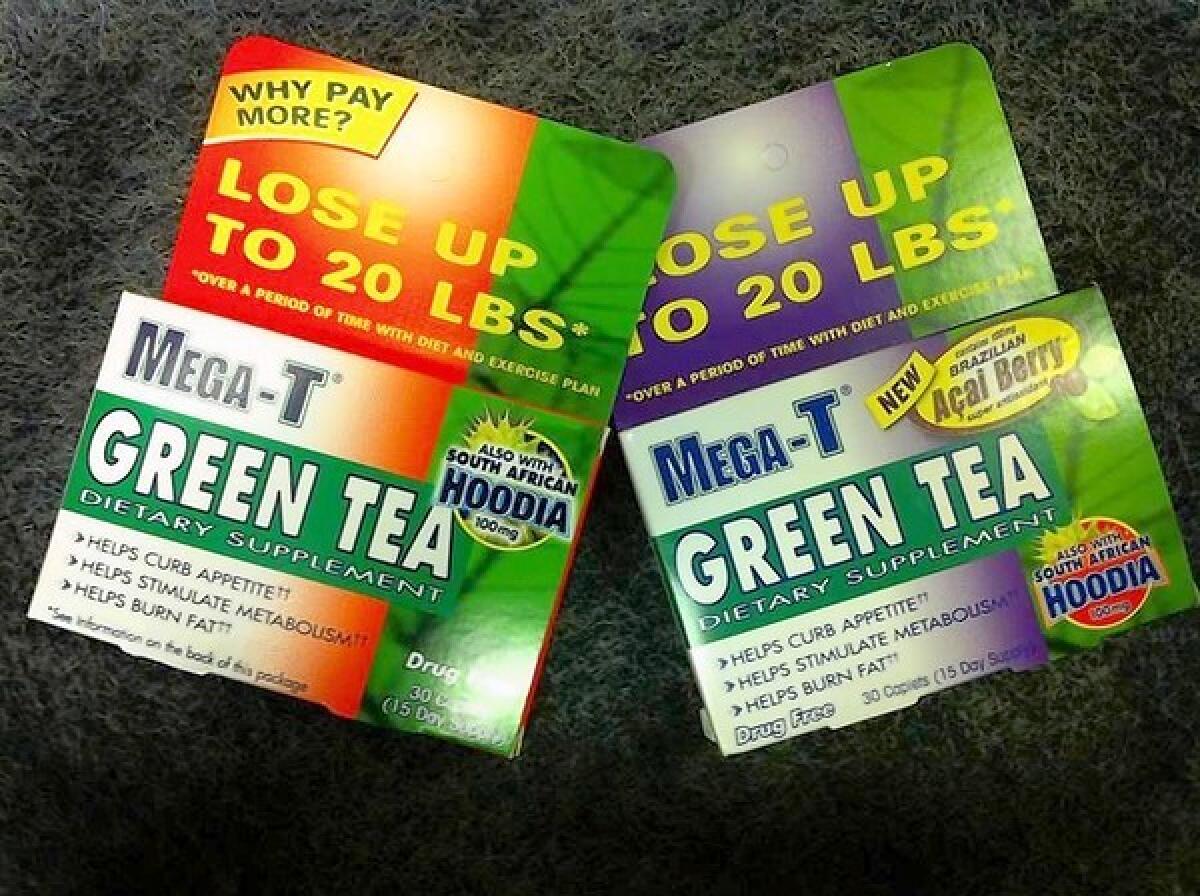

Walk through the supplements aisle of any big drugstore and it’s hard not to come away with the impression that the various bottles of pills have medicinal value.

At the very least, the FDA should require that supplement companies demonstrate upfront that their products can do what they say — perhaps not as meticulously as testing for prescription drugs, but at least enough to satisfy modest safety concerns.

Cracking down after a health-related product reaches store shelves seems wholly inadequate.

Particularly at a time like this.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.