Eli Broad was an ‘unreasonable’ boss. People loved working for him

- Share via

Soon after a young Bruce Karatz joined Kaufman & Broad in 1972, he was called up to the office of Chief Executive Eli Broad and told to scout out a property the home builder was considering buying in Riverside.

Karatz submitted his report, but when he didn’t hear back he inquired if Broad had read it. The response? “Is this the best you can do?”

Karatz worked on it some more but was met with the same question. Finally, after being asked again on the third try if this was the best he could do, Karatz responded, “I’m sorry, but yes, sir.”

Broad replied, “Well, then I’ll read it.”

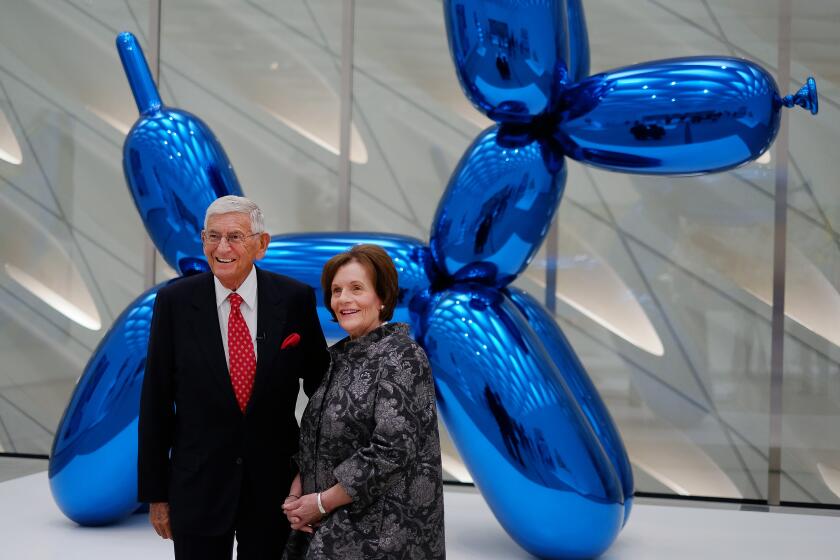

Photos: Eli Broad, philanthropist, art collector, builder, created part of the Los Angeles landscape

Eli Broad, philanthropist, art collector and builder, has died at 87.

In his 2012 memoir, Broad acknowledged that Karatz felt a bit “jerked around” by the stunt. It was a tactic Broad wouldn’t need to use again because Karatz now understood his “best effort” was expected.

Two years after he started, Broad sent Karatz to France, where he turned Kaufman & Broad into one of the country’s leading home builders. He also distinguished himself with a marketing gambit Broad loved: building a model home on the roof of an old Paris department store that drew hundreds of thousands of walk-throughs.

Eventually, Karatz became chairman and chief executive of the company, later renamed KB Home.

“That set the tone,” reflected the now-retired Karatz, who at 75 still has a vivid memory of the Riverside incident and spoke after Broad’s death last week. “I was pushed to do absolutely the best you can do. It was something that I appreciated. It drove me, and I think I passed it on to a number of other people that I worked with.”

Broad, who died Friday at age 87, has been lauded as a civic leader and philanthropist who founded two Los Angeles Fortune 500 companies — the home builder and, later, financial services giant SunAmerica. But he also had a reputation for being difficult — something he was well aware of and even turned into the primary motif of his aptly titled memoir, “The Art of Being Unreasonable.”

Eli Broad stepped in when L.A. hit a low. He changed the city in ways he didn’t always expect.

Broad made no apologies for his demanding style, believing that being unreasonable was the foundation of his success. And for several future business leaders, who cut their teeth at Kaufman & Broad and later at SunAmerica, that approach paid both them and their boss large dividends. They recall a supervisor with an extraordinary work ethic who was always impeccably prepared for meetings and a voracious consumer of books — even though he had dyslexia, something he didn’t know until his own son was diagnosed with it.

“He worked harder than anyone else. Sunday was the same as Monday. Really, he went full speed seven days a week, with this view: ‘I want to get as much done today because who knows whether tomorrow will come,’” Karatz said.

Broad chalked up a lot of his achievements to always being on the lookout for something new, noting in his memoir the first rule of success is to ask: “Why not?” He said it was something that came naturally to children but was lost on adults who accepted the status quo.

He attributed his first big success — his decision to build homes without basements — to the rule. It was unheard of in the late 1950s in Detroit, but it made the homes affordable to the growing families of the postwar era.

Broad came to find that some of the best ideas sprang from young talent, writing in his memoir that he often preferred to hire youth over more experienced candidates. “We captured bright young talent, listened to new ideas and — when they made sense — ran with them,” Broad wrote. In many ways, he predated Silicon Valley’s innovation mantra, something that wasn’t always easy on those young employees.

“I used to joke around and say that if you achieved 90% of a goal that he had set for you, it was the equivalent of achieving 150% of a goal another reasonable person would have set,” said Oaktree Capital Management CEO Jay Wintrob, 64, who worked for Broad at SunAmerica.

SunAmerica had its roots in Sun Life, an old-line insurer Broad had acquired to hedge his volatile home-building business. It was transformed into a financial powerhouse by introducing variable- and fixed-rate annuities, which Broad called “mutual funds in life insurance wrappers.” The idea was such a success SunAmerica was acquired for $18 billion by insurer AIG in 1998.

“You had to have a good idea. It wasn’t just everybody gets five minutes to tell what they think,” Wintrob said. “It was fun. It was exciting. And, boy, he could dish it out — and he could take it.”

Jeff Koons says his first ‘Balloon Dog’ sculpture came into being only with the patience and pocketbook of Eli Broad, who died Friday at 87.

Billionaire Bruce Karsh, 65, who worked for Broad for about 2½ years, typifies that free-for-all. He was a 28-year-old lawyer at the blue-chip L.A. law firm O’Melveny & Myers when he was poached by Broad in 1984 to become his assistant. Karsh came recommended by another attorney, Richard Riordan, who had not yet been elected mayor. Karsh was offered a job 20 minutes into his interview.

The offer prompted Karsh to perform due diligence on his prospective employer, and he discovered that Broad was known as a highly demanding boss. “He had that reputation back in the day, but I thought what’s the downside? I’ll go learn a lot. I can always go back and be a lawyer,” said Karsh, co-chairman and chief investment officer of Oaktree, a Los Angeles alternative asset manager.

“I was learning from a great teacher. He was very kind. He was very generous with his time,” recalled Karsh, who in his time working for Broad was regularly at his boss’ side, including on trips to meet with Wall Street luminaries. “The thing I learned very, very quickly about Eli is that you very well better be prepared and do your homework because he asked a ton of questions. He didn’t suffer fools. [And] even though I was young he seemed to be genuinely interested in my thoughts.”

Broad asked Karsh to evaluate debt the insurance company held in Johns Manville Corp., which had declared bankruptcy due to billions of dollars of asbestos-related liabilities. Karsh came back with a surprising recommendation: There was an upside in the cheap debt and Broad should consider buying some more.

“He liked that. He was the kind of guy that was interested in out-of-the-box thinking,” said Karsh, who credits Broad with being one of the first distressed-debt investors long before it was acceptable on Wall Street.

The recommendation prompted Broad to hang on to the debt, which turned out to be the right call. And after Karsh left Broad in 1987 to join Los Angeles asset manager TCW, Broad invested his personal and company money in Karsh’s first distressed debt fund in 1988, which Karsh said was instrumental to his success. Karsh later left TCW to co-found Oaktree, the world’s largest manager of distressed debt. Karsh now has a net worth of $2.1 billion, according to Forbes.

Running a Fortune 500 company is an enormous, time-consuming task, and Broad comes across in his memoir as almost rigid in his desire to use his day efficiently. He didn’t play golf because it wasn’t worth the time, believing an early breakfast can produce just as many business connections. He had a strict three-hour rule for parties, openings and other events, saying there were few things in life that needed to last longer.

But Wintrob said that a key trait that accounted for Broad’s success was his ordinariness, despite all the other attributes that made him remarkable. “Eli was a very normal person, and he understood people. So he understood the joys and benefits of ownership, purchasing your first home. He understood as people age they become more and more concerned about their future. These are not really complicated themes,” Wintrob said.

Although Broad would fit into the classic definition of a workaholic, Wintrob said he didn’t perceive him as one because he had so many interests and passions outside of business. After retiring, he famously devoted himself to education, the arts and civic affairs. Karatz said his friend motivated him to expand his own involvement beyond the home builder, with Karatz chairing the California Business Roundtable at one time.

Broad also loved vacations and was an avid traveler.

Karatz, who traveled the world with Broad, remembers a trip to Laos that prompted Broad to get a dozen or more books on the country to better prepare for the visit. He also traveled with large bags of reading material he wanted to catch up on. In his memoir, Broad wrote that it’s important to spend some of each day “learning about the present and the past” because history is “scattered with clues to the future.”

Karatz said that his friend wanted to be sure “he didn’t miss anything.” It was a life that Karatz believes Broad lived with few regrets. Aside, perhaps, from “thinking about what he could have accomplished if he could live another 10 years,” he said.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.