How do you make a 44-year-old animatronic rodent appeal to today’s kids?

- Share via

Chuck E. Cheese has seen a lot in 44 years. The namesake rodent at America’s leading children’s entertainment center and pizza chain has watched generations grow up, playtime trends evolve and video games move from the arcade to the home. He’s even seen his own image change, from a rat in the company’s early days to a mouse after a rebranding campaign.

The fact he’s still here is a testament to his employer’s surprising perseverance.

Sitting in front of what appears to be an Impressionistic take on Chuck E. Cheese, complete with a bowler hat and bowtie, David McKillips, chief executive of Chuck E. Cheese parent company CEC Entertainment, credits the company’s longevity to its embrace of technology. It’s an ideology, he said, that stems from its founder, video game titan Nolan Bushnell, of Atari fame.

“We keep embracing innovation decade after decade,” McKillips said. “We don’t have ball pits anymore. But we have the greatest video games and arcade games and interactive dance parties.”

The path has not been easy for Chuck E. Cheese, especially recently. Just in the last year and a half, there were months of restaurant shutdowns during the pandemic, the permanent closure of more than 30 locations and a filing for bankruptcy protection. Yet its culture of adaptation has kept Chuck E. Cheese alive when some of its competitors have died young.

The trampoline park industry — once among the fastest-growing franchise businesses in America — can trace its roots to an injury-addled 1960s craze and an extreme sport you’ve never heard of.

The first Chuck E. Cheese opened in 1977 in San Jose and quickly proved a hit. The children’s game center and pizza parlor with the distinctive animatronic animal band expanded, thanks in part to the rising popularity of video games, according to a 2017 case study published in the Journal of Business Cases and Applications.

Chuck E. Cheese’s parent company went public in 1988 and by 2005, Chuck E. Cheese had grown to 500 locations.

But by the early 2010s, sales started to slow, leading to a revamp of the main character himself in 2012. Chuck E. Cheese lost his ‘90s-chic fingerless gloves, the backward baseball cap and casual shorts and took on a more rocker appearance with jeans and an electric guitar.

A rebrand didn’t solve all the chain’s problems. In 2014, CEC Entertainment was acquired by private equity firm Apollo Global Management in a leveraged buyout. The firm invested in an effort to make its 577 restaurants more palatable.

Over the years, Chuck E. Cheese has changed its menu to include new kinds of pizzas, such as pies with mushrooms and fresh spinach and kid-geared desserts such as multicolored unicorn churros. The chain also tried to better appeal to adults by serving alcohol, a move that could boost sales but also may have led to increased altercations at its restaurants, according to the 2017 case study. (“Consider the following description of the restaurant offered by an alderman in Milwaukee, he compares the local Chuck E. Cheese to ‘something out of a Quentin Tarantino film... there is alcohol and pistols being brandished,’” the study said.)

Unlike some of its counterparts in the competitive and fast-evolving children’s entertainment sector, Chuck E. Cheese has worked to modernize its amusements and operations.

The company moved away from its traditional paper tickets — the paper stock of which cost $6 million to $7 million annually — to an e-ticket platform. It releases albums of Chuck E. Cheese songs on Spotify and is adding digital dance floors.

The company also started expanding its business beyond its physical play places. When the COVID-19 pandemic shut down locations and stay-at-home orders boosted demand for food delivery, Chuck E. Cheese opened a ghost kitchen called Pasqually’s Pizza & Wings (named for one of the members of the animatronic rodent’s band).

Frozen Chuck E. Cheese pizza can now be found at Kroger stores, and parents can buy birthday party packages of balloons, pizza, party bags and cake to celebrate at home. (Birthday parties at Chuck E. Cheese locations remain a big business — the company says it hosts 500,000 birthday parties a year in the U.S.)

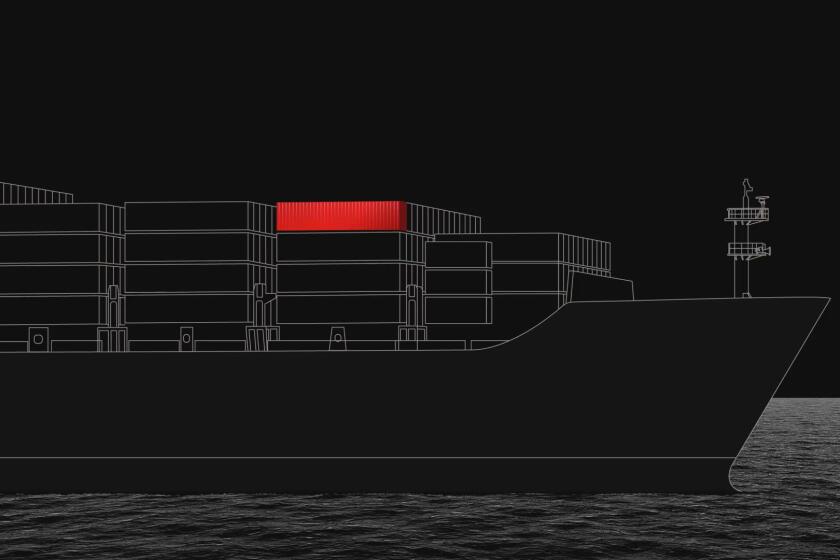

Follow a container of board games from China to St. Louis to see all the delays it encounters along the way.

A failure to adapt to trends is what ultimately led to the downfall of a Chuck E. Cheese contemporary, Discovery Zone.

The indoor play place company was at the top of its game in the early 1990s. It was a Wall Street darling that expanded from eight stores to more than 300 and seemed poised for greater things after it got the backing of the wildly successful video rental firm Blockbuster.

Discovery Zone acquired its biggest rival and bought out franchisees. But revenue didn’t increase in parallel with the company’s sprawling network of locations. There were too many Discovery Zones near one another — or smaller rivals — which only heightened competition.

Parents got bored while their children played at the facilities, and the original concept of an indoor playground barely changed throughout the company’s lifetime, despite technological advances and the advent of video games, making repeat visits less appealing.

The company also faced the daunting challenge of how to churn out revenue during weekday school hours and expand its customer base beyond young children. During evening hours, some Discovery Zones turned into nightclubs for teens or offered babysitting services in its stores.

In 1996, the company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. Months later, the chain started closing dozens of locations. In 2001, after a 12-year run, Discovery Zone shut down completely.

Chuck E. Cheese took advantage of its competitor’s struggles. It purchased 15 Discovery Zones during a time when the trends pointed toward physical play such as zigzagging SkyTubes and ball pits, McKillips said. Those locations were combined with Chuck E. Cheese’s menu and games and rebranded under the Chuck E. Cheese name.

But even as Discovery Zone faded, additional competitors emerged. New family fun centers came on the scene, and in 2004, the first Sky Zone opened, sparking a nearly two-decade boom in trampoline parks.

A 2019 attempt to take Chuck E. Cheese’s parent company public again fell apart, and in June 2020, the chain filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection after it saw prolonged store closures during the pandemic. Pre-pandemic competition had also emerged from other active play companies, including trampoline parks, laser tag facilities and Dave & Buster’s.

McKillips, who joined the company in January 2020, has spent much of his tenure dealing with the twin chaos of the pandemic and the financial restructuring.

“The market conditions are something that we’re dealing with like every other family entertainment company,” he said.

The chain emerged from Chapter 11 in December and still has more than 500 Chuck E. Cheese restaurants around the globe.

Part of the staying power, McKillips says, is the likeability of Chuck E. Cheese himself, along with bandmates such as Mr. Munch, who looks like a cross between McDonald’s Grimace and Barney’s BJ, mustachioed chef Pasqually and avian musician Helen Henny. The characters, he said, are recognizable by generations of children and provide a constant in the midst of changing trends and attractions.

“It’s about the positivity that the characters bring,” he said. “It’s all about that celebration. These characters are having fun.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.