Column: Those math and reading scores were horrible, but beware of the political spin

- Share via

There’s nothing good to say about the newly-released national test scores in reading and math for fourth- and eighth-graders, showing sizable declines in the vast majority of states as a result of the pandemic.

“The results ... are appalling, unacceptable, and a reminder of the impact that this pandemic has had on our learners,” Education Secretary Miguel Cardona said after the scores from the National Assessment of Educational Progress, or NAEP, were released Sunday.

The scores demonstrate the dangers of complacency about how our public school systems serve K-12 pupils — especially Black students and those from other vulnerable communities.

The results ... are appalling, unacceptable, and a reminder of the impact that this pandemic has had on our learners.

— Education Secretary Miguel Cardona on the NAEP national report card

But there’s another danger suggested by the reactions to the NAEP scores: the danger of using the results to justify school policies that were made on ideological grounds and based on what are by any standard incomplete and confusing data.

For example, here’s Florida’s Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis, a sworn opponent of anti-pandemic public health measures, crowing on Twitter that his state’s NAEP results “prove that we made the right decision” to keep schools open.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

DeSantis was echoed by Fox News political analyst Brit Hume, who tweeted that the scores were “a result of the school shutdowns, which many warned would have precisely this effect.”

Not so fast, guys.

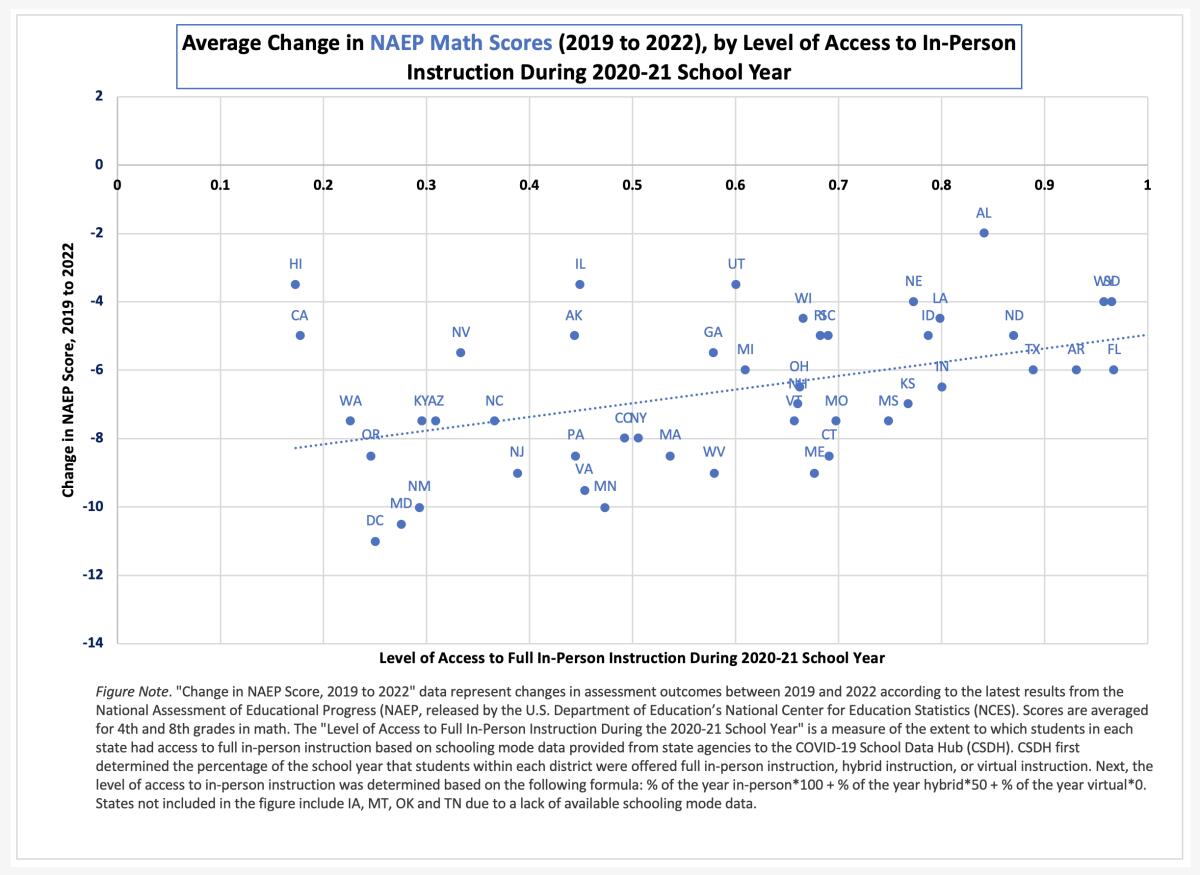

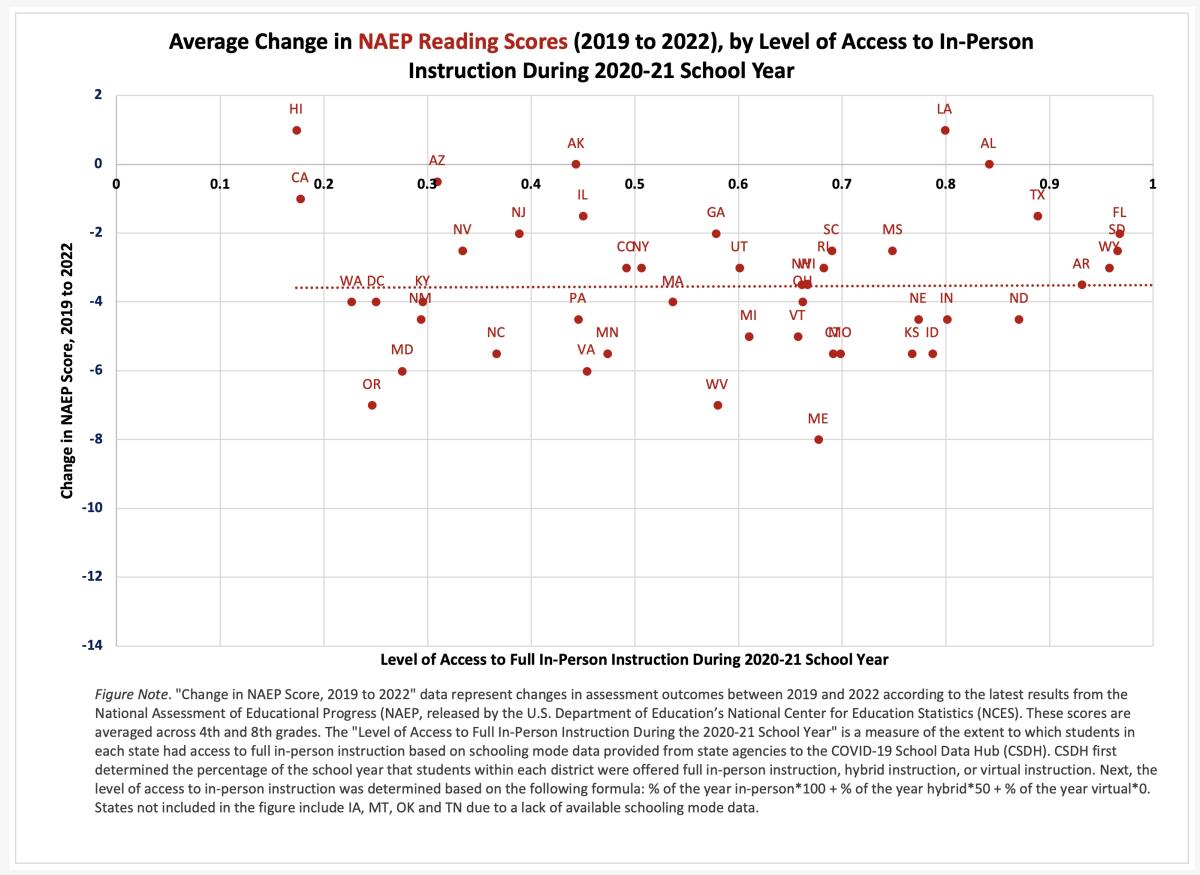

“There’s a tremendous amount that we don’t understand,” says Emily Oster, an expert on health economics and statistics at Brown University. “This is not a single-factorial case.” That said, Oster and colleagues have compiled evidence suggesting that pupils have done better with more in-person instruction.

There’s no disputing the role of the namesake of UC Hastings in an American genocide. His name doesn’t belong on UC’s law school.

In many respects the NAEP scores are equivocal about the impact of remote versus in-person learning, and in some respects contradictory. That’s unsurprising, given the multifarious impact of the COVID pandemic throughout society, from disruptions at the household level to the broad community.

Through June 30, 2021, more than 140,000 children lost a parent or other caregiver, according to researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — “a hidden and ongoing secondary tragedy caused by the COVID-19 pandemic,” the CDC said.

Let’s take a look at what the NAEP’s national report card shows.

Since Gov. DeSantis took pains to declare victory, let’s compare his state’s record to that of California. The two states could not be further apart in their approach to pandemic-era schooling. As my colleague Paloma Esquivel reported, in California, the vast majority of schools were closed until spring 2021; in Florida, schools could reopen starting in fall 2020.

“It was pretty clear by the fall of 2020 that schools were not locations of significant COVID spread, so it was possible to have them open,” Oster told me. “Keeping schools closed past that point was understandable, since it was a very complicated time, but it was not necessary from the standpoint of data, in my view.”

Oster’s figures show that during the 2020-21 school year, California schoolchildren spent more than 71% of their days in “virtual instruction” (that is, remote teaching) and the rest in full in-person instruction (about 6.8% of their days) or “hybrid” instruction (21.8%). In Florida, 97% of student days were in full in-person mode and the rest in remote instruction.

On the whole, the statistics were nothing to brag about. Both states showed percentage declines in scores from 2019, pre-pandemic, to this year in three of the four categories (fourth- and eighth-grade reading and math).

But on the whole, California did better than Florida. In eighth-grade reading, California showed no change since 2019, but Florida students’ proficiency declined by four percentage points.

Who paid for the college education for GOP critics of Biden’s student loan relief? The taxpayers, that’s who.

Florida’s results were one percentage point worse than California’s in fourth- and eighth-grade math. California fourth-graders’ reading scores declined by two points, and Florida stayed level.

The overall averages showed California students losing five percentage points since 2019 in math, while Florida students lost six points. In reading, California students lost one point and Florida’s lost two.

Other states that reopened schools relatively quickly also showed significantly below-average results, including Kansas, Maine and Idaho in reading and Kansas, Maine, Mississippi and Idaho in math.

The data generally paint California and Hawaii as outliers in their results, showing declines significantly less severe than the national averages despite having the most stringent school-closing policies in the country.

That’s what implies the limits of tying student achievement narrowly to school closings. One factor is the effort that some states, including California, put into remedial programs during the pandemic and after it ebbed. The state allocated nearly $24 billion to pay for tutoring, extended summer school and other educational assistance.

One trend that can’t be ignored is the continually lagging performance of Black, Latino, low-income and other historically underserved students. As The Times reported, 84% of Black students and 79% of Latino and low-income students did not meet state math standards in 2022, a bigger shortfall than that of white students or the student population as a whole.

Disney’s money has controlled Florida politics for more than 50 years. Now the politicians are showing their ingratitude.

The NAEP scores indicate that the gap between white students and Black, Latino and low-income students widened during the pandemic.

The pandemic-era record shouldn’t obscure that achievement scores in American education were dismal even before the pandemic. Nationwide, about one-third of students met proficiency standards in math and reading in 2019.

There’s little evidence that reforms such as charter schools are an answer; according to the NAEP report card, average scores in math, reading and science are worse in charter schools than in conventional public schools, and the gap grows larger from fourth grade to eighth grade to 12th.

Another trend that has grown more marked since the advent of the pandemic is pressure on teachers, who have been leaving the profession by the hundreds of thousands.

Customarily underpaid in relation to the importance society places on their role in preparing America’s youth for adulthood, teachers in some states face added scrutiny over their teaching methods and classroom curricula.

That’s especially notable in red states, where conservatives have tried to make partisan hay over such themes as “critical race theory” and gender studies.

As recently as Monday, during a debate with his Democratic opponent Charlie Crist, DeSantis took a shot at how history is taught in public schools, calling for “accurate history” — essentially eliding the racial elements of America’s founding.

Adding political litmus tests to public school teaching or boasting about pandemic policies that may or may not have had anything to do with student achievement won’t solve America’s persistent shortfall in education.

They’ll only make the educational environment worse for students and teachers alike. That’s the road down which we’re traveling.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.