She didn’t need the risky surgery. County doctors talked her into it anyway, lawsuit says

- Share via

After a stay at a Los Angeles County public hospital, Bernetta Higgins was home and feeling better when one of the surgeons called.

The doctor, Rodney White, and his nurse told Higgins to return to the emergency room at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center and tell the staff she had chest pain, according to an email from the nurse documenting the call. Higgins said she wasn’t hurting, but she followed the doctor’s orders and went to the ER. White had told her earlier about “a new experimental surgery” that “would take care of it” — a tear in the lining of her aorta.

For the record:

1:33 p.m. March 28, 2023This article was updated to clarify the damages awarded to Dr. Timothy Ryan. The jury awarded Ryan $2.1 million for emotional distress damages, finding that his acts to stop his employer from filing a false insurance claim were a substantial motivating reason for the county to take adverse actions against him. It also has been updated to include court records that reflect a nurse’s notes stating that Higgins complained of chest pain.

White signed papers to readmit her and four days later implanted two $15,000 devices into Higgins, then 65. He told her the surgery would take 90 minutes, she testified. Staff wheeled her away in the morning. It wasn’t until night that her mother saw her again. The family learned she had suffered a stroke.

“They were talking to me and I couldn’t understand them,” Higgins recalled. “My mom said, ‘What’s wrong with her?’”

At the time of the surgery, White and his partner, another Harbor surgeon, were on the payroll of Medtronic, the device’s manufacturer. Drug and device companies often pay doctors to promote and test their products and to teach other physicians about them. Those payments are legal unless they are knowingly paid as a kickback for the doctor’s use of a product — which the surgeons and county claim was not the case here.

White’s partner testified he was paid by Medtronic only to teach courses for other doctors, including the procedure in which the two implanted the devices into Higgins. White and another doctor also said they were paid for a course held during her surgery. White later changed his testimony, saying the instruction he was paid for happened during an earlier surgery that day.

The story of Higgins’ experimental treatment in 2014 only recently became public when a lawsuit brought by Timothy Ryan, the surgeon who first treated her at Harbor, went to trial.

Ryan claimed that, based on medical guidelines for treatment of Higgins’ illness, she did not need the surgery.

“This was done purely to line doctors’ pockets.”

— Timothy Ryan, vascular surgeon

In his lawsuit, he said no doctors were trained at many of the surgeries claimed to be Medtronic courses. And he contended that the surgeons went through patient charts to find candidates for the expensive medical devices — whether they needed them or not.

The experimental surgery on Higgins, who is Black, was part of an extensive research operation that doctors created at Harbor, whose patients are mostly poor and people of color.

The research operation has aided drug companies and device makers that use the studies to test their products and promote them. County doctors who have signed industry research agreements receive outside payments for the experimental work. Patients are asked to sign waivers saying they agree to the experiments’ risks.

Ryan said in the suit that county officials and Harbor doctors retaliated against him when he tried to get them to investigate Higgins’ care and the money the surgeons had been receiving for years from Medtronic.

“These are the most vulnerable people in L.A. County,” he said of Harbor’s patients. “This was done purely to line doctors’ pockets.”

A jury awarded Ryan $2.1 million in March 2022 for emotional distress damages, finding that his acts to stop his employer from filing a false insurance claim were a substantial motivating reason for the county to take adverse actions against him.

County officials disagree with Ryan’s account, including his allegation of retaliation. They say Higgins’ care was “medically sound and within the standard of care” and that White “acted appropriately.” They added that they “supported his research relationship with Medtronic.”

Medtronic said in a statement that Ryan’s claims do “not reflect Medtronic practices then or now.” The company said it had “rigorous processes” to ensure its interactions with physicians “are consistent with government law and regulations.”

White declined to comment.

Ryan has filed an appeal, saying a judge’s decision before the trial had worked to wrongly limit how much the jury could award him. In December, a judge said the county must pay $3.2 million to cover fees of Ryan’s lawyers. The county says it is appealing that decision and the jury’s verdict.

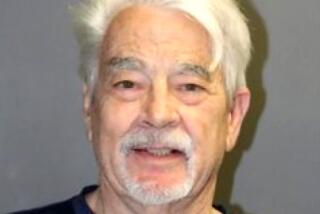

After graduating from Harvard Medical School and residency work at Stanford and the Cleveland Clinic, Ryan arrived at Harbor in October 2013. He was excited to join the hospital’s team of vascular surgeons, where White would be his supervisor.

Like dozens of other doctors at Harbor, White was both a physician at the eight-story public hospital in Torrance and a scientist at the private research facility, now known as the Lundquist Institute, that sits next door on county land.

The county Board of Supervisors granted the private research group access to Harbor’s “facilities, staffing, patients and medical records,” according to the agreement.

The arrangement is unusual for a government hospital, or any hospital with a large research operation, because it allowed an outside private group to oversee and manage the studies performed on its patients, who at Harbor are mostly low-income, including many not fluent in English.

The county told The Times it believes the research operation at the hospital was “essential to the advancement of medicine” and noted the recent nationwide push to put more minorities into clinical trials when 75% of participants are now white.

It has long been controversial for doctors to recruit the poor and other vulnerable people into experiments because of repeated historical scandals where they were misled. One egregious example: a trial that began in 1932 by the U.S. Public Health Service called the “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male.”

Other government safety-net hospitals allow clinical trials, but unlike Harbor, most have internal committees to monitor the research and make sure patient volunteers aren’t misled or taken advantage of.

Lundquist, a private nonprofit, is not subject to public records laws. Its executives told The Times the institute follows all federal laws governing clinical trials, but they declined to answer a list of questions.

According to its website, Lundquist solicits companies, the government and foundations for research grants. It then uses that money to perform and manage the trials led by Harbor doctors and to pay its executives and scientists.

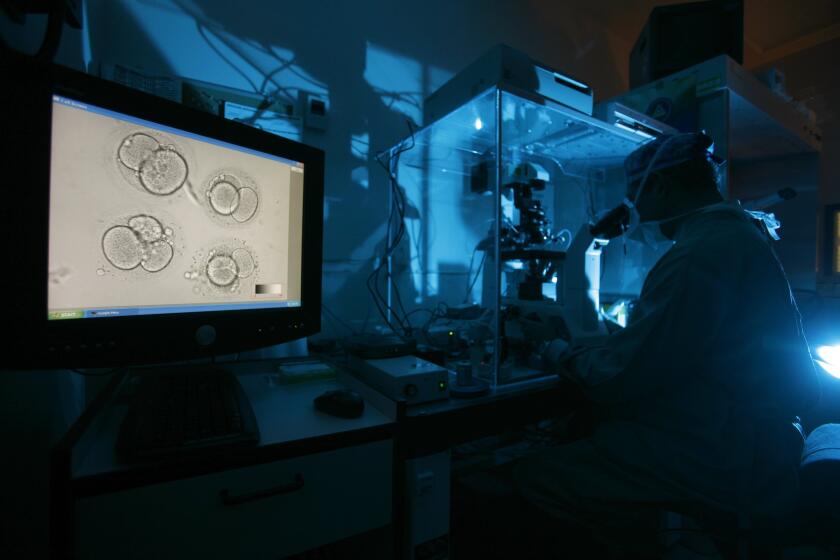

An L.A. couple have sued Fujifilm Irvine Scientific, alleging the company’s mineral oil used in the IVF process destroyed their embryos.

Lundquist currently has 600 ongoing research projects, its website says.

The institute says it aims to take discoveries made by Harbor doctors and turn them into commercial products.

“We are actively seeking to build on our history of successful collaborations with companies both large and small,” it states on its website.

Higgins knew none of that when she was admitted to Harbor with abdominal pain in December 2013, where Ryan became her doctor.

A CT scan showed her pain was caused by an aortic dissection. The life-threatening condition occurs when the lining of the body’s main artery tears, causing blood to rush through and create a second channel within its layers.

If the weakened aorta ruptures, the patient can quickly die. The tear can also heal on its own, which Ryan found was happening for Higgins, he testified.

Current medical guidelines, which are recommendations based on a review of the science by experts, say surgeons should avoid surgery when the tear is healing and pain has subsided. That’s because surgery, either by cutting open the patient’s chest or by the new, less invasive method of inserting stent grafts through arteries in the thigh, both come with high risk of stroke, paraplegia and death.

Higgins went home without pain after less than a week at Harbor.

Ryan didn’t know that White had visited Higgins’ room before she left. White had told her, according to Higgins’ later testimony, that he could do an experimental procedure to “close the leak.” It would avoid having a surgeon cut open her chest, which would be required if her aorta did not heal, White had said.

“I was so excited that I don’t remember anything else,” Higgins said.

White and his partner Carlos Donayre, another vascular surgeon, had signed agreements with Medtronic dating back to at least 2000. A key part of their agreements were “courses” where other physicians or Medtronic employees observed the two as they implanted aortic stent grafts.

Several companies make stent grafts, but the contract Donayre signed in 2011 said he must use Medtronic’s devices to get paid the $2,500 fee. “All … courses shall … use FDA-approved Medtronic components and accessories,” it stated.

Medtronic had hired White to do even more. Among other things, White was paid to write articles for medical journals on subjects suggested by the company. And he helped lead clinical trials that Medtronic needed to submit to regulators for approval.

At the time Higgins was admitted, White was working on 36 research projects for Medtronic, according to Lundquist data. That year, the company paid him as much as $100,000, White testified in court.

Medtronic told The Times that hiring physicians was a common practice in the industry. The company, whose operational headquarters are in Minnesota, denied Ryan’s claim from the lawsuit that its contract requiring surgeons to use its products in the courses was effectively a kickback. “If a physician is training another physician on the use of Medtronic products, it necessarily involves our product,” it said.

“Medtronic relies on and defers to the independence of physicians’ legal and ethical judgments, as to what is appropriate care,” the company said.

Donayre did not respond to email messages seeking comment.

Device makers have repeatedly paid millions of dollars to settle lawsuits claiming their payments to surgeons were kickbacks for using their products.

In 2020, Medtronic paid $8.1 million to settle federal prosecutors’ allegations that it had given illegal kickbacks to a South Dakota neurosurgeon to get him to use the company’s devices. Prosecutors described the kickbacks as payments Medtronic had provided to cover the cost of more than 100 events held at a restaurant the surgeon owned. Medtronic said the case involved “a small number of sales employees,” who were later disciplined or terminated.

In July, Biotronik Inc. paid $13 million to settle federal prosecutors’ allegations that it had excessively paid surgeons to train its employees in courses during surgeries where its cardiac devices were implanted. Lawyers for the whistleblowers provided evidence showing that some Biotronik employees were “trained” 100 times by doctors receiving a $400 payment for each surgery said to be educational. In agreeing to the settlement, Biotronik denied the allegations.

“Patients deserve to know that their device was selected based on quality of care considerations and not on improper payments from manufacturers,” said Brian Boynton, principal deputy assistant attorney general, in announcing that settlement.

In November 2013, a month after Ryan started at Harbor, a Medtronic executive offered him a proposal where he would receive as much as $4,000 a day for work on the company’s programs at Harbor, Ryan said. “It didn’t specify what I had to do for that money,” he said. “It didn’t seem right.” He declined.

On Jan. 8, 2014, he was copied on an email from White’s nurse discussing his patient Higgins.

“Just wanted to inform you that we informed Ms. Higgins to come through the ER tomorrow morning complaining of chest pain,” the nurse wrote to the staff on White’s team. “Dr. White & I spoke to the patient earlier this afternoon. This is our best option.”

Higgins’ sister drove her to the ER in the morning. She never complained of chest pain to the staff, who seemed to be expecting her, Higgins told The Times. One triage nurse later testified she did not recall Higgins, but said her notes reflect Higgins complaining that “chest pain started today with the feeling of something [ripping] apart.” Higgins said one staff person told her, “Oh you’re Bernie Higgins. Dr. White is supposed to come and talk to you.”

She waited so long in the ER she fell asleep, stretched across two chairs.

The drug Makena doesn’t reduce the risk of preterm birth, a study found, and the FDA recommended it be taken off the market. Its maker has refused.

White wrote a report admitting her to the hospital that night that said Higgins “woke up early this morning with chest pain … accompanied by nausea and dizziness.” He wrote that she had then called his office and his staff “instructed her to go to the ER.”

Higgins said none of that was true. She denied it in sworn testimony and a signed declaration.

“It was corruption all the way through,” she said.

White declined to respond to her allegation of corruption.

Higgins spent a month at Harbor recovering from the stroke before the county moved her to a rehabilitation center. For another two months, she lived at that facility, learning to talk again and do tasks that were once simple.

“I couldn’t even remember how to use a phone,” she said.

She had worked at a law firm before the stroke. Now she struggles to remember how to navigate the streets of her Silver Lake neighborhood.

“Bernie was a fast typist. She skipped grades in school,” said her mother, Vernetta Petitt of Compton. After the surgery, “she couldn’t even write her name.”

“The joy of my life was reading. Now I can’t read more than a blurb.”

— Bernetta Higgins, who suffered a stroke after a risky surgery

The bill for the surgery and nearly four weeks of hospital care after the stroke was $273,871, according to a county document. The federal Medicare program paid $23,682. The rest was covered by county funds. Officials would not say how much her two-month stay at the rehab center cost.

In a statement, county officials said that Higgins was “fully informed of the risks of the procedure” and signed a consent form agreeing to be in the study. “Complications from surgery are a normal part of medicine,” the county said.

Higgins said she had been so overwhelmed in the hospital that she didn’t read the nine-page consent form that listed stroke and death as possible outcomes. “I signed something without looking at it,” she said.

(She filed a lawsuit against White and the county in 2017 with claims that included fraud and medical negligence. Her lawyers based the case on the complaint Ryan had filed. They did not have key documents that later became part of his case. A judge denied most of the claims except for the allegation of fraud, and her lawyers later asked for the lawsuit to be dismissed.)

White and his team regularly searched for patients who might be candidates for Medtronic’s devices and could be the subject of the company’s courses, according to emails disclosed as part of Ryan’s lawsuit.

“Do we have any leads on a dissection case or two for the March 10th course?” wrote George Kopchok, a biomedical engineer who was on the team, to White and his nurse the month after the doctors operated on Higgins’ dissection.

Other emails to White and his nurse came from the company’s sales reps. The sales reps urged White to get the county to pay for the devices he had implanted in patients so they could get their commission.

Medtronic told The Times it did not pay doctors to endorse or recommend its products. Yet the company repeatedly used comments from White in its marketing materials to promote the device known as the Valiant Captivia.

Two weeks after Higgins’ surgery, Medtronic quoted White in a press release about the Valiant. “Data out to one year continue to show positive aortic remodeling,” White said of his patients’ outcomes in the release.

“This new form of therapy looks ... promising,” he added in a video on Medtronic’s website.

Medtronic told The Times that White was not paid for his quote in the press release but was simply “stating his experience” in using the device in a clinical trial where Medtronic had paid him to enroll patients. The company said he and other physicians were paid for the video but “were asked to share their personal experience and expertise only.”

In the courtroom in March, the county’s lawyers put an expert, Niten Singh, a vascular surgeon at Seattle’s Harborview Medical Center, on the stand. He told the jury the procedure was needed because Higgins had gone to the ER with chest pain.

Under cross-examination by Ryan’s lawyer, Singh acknowledged that the county’s lawyers had not given him Higgins’ testimony to review. In it, Higgins said she did not have chest pain and had gone to the ER only because White told her to.

Asked if he would have offered Higgins surgery if he knew she did not have pain, Singh said no.

Instead, he said, he would have monitored her aorta through continuing visits and CT scans.

Whether Higgins needed the surgery was also a key question for White and Donayre during the trial.

In a deposition before the trial, White testified Higgins had “a lethal kind of problem” — that she had both chest pain and blood leaking from her aorta into her chest.

Pressed to explain why he then waited four days to perform the surgery, White explained that Higgins was part of a Medtronic course scheduled for that Monday.

“We settled her down,” he said, “got her figured out, and did her then.”

White changed his testimony on the witness stand.

He said Medtronic had paid him $2,500 for a course on the day of Higgins’ surgery but that it involved another patient.

White again said Higgins’ surgery was necessary because she had pain and her aorta was deteriorating.

Ryan’s lawyer showed jurors the CT scan the surgeons had ordered for Higgins the day after White admitted her.

It showed her aorta was improving. Singh, the county’s expert, testified the scan showed the fluid around her lungs had diminished and that blood was no longer freely flowing through the second channel that had formed in the aorta’s lining. Instead, it had clotted. The scan showed no blood outside her aorta, Singh said.

But in his report on the operation, White’s partner Donayre had written that she had a “left hemothorax.” That bleeding into her chest, he wrote, was the reason for surgery.

Asked about the CT scan that showed no such bleeding, White pivoted.

He told the jury he had found another problem not mentioned in Higgins’ medical record. White said he had “reconstructed” the CT scan with an earlier test and found a “rapid enlargement” of Higgins’ aorta.

Ryan’s lawyer showed the jury notes that White and the other doctors had written at the time of the surgery in Higgins’ chart. There was no mention of an enlargement. And Singh, the county’s expert, said he found that portions of her aorta were “slightly smaller” just before the surgery.

White continued to testify that Higgins needed the surgery because she had chest pain.

“She was on a number of pain medications, starting with morphine,” he told the jury.

Ryan’s lawyer showed the jury Higgins’ list of medications. There was no morphine or any other pain drug.

White responded that a drug she was taking to reduce blood pressure could be considered a pain medication.

White entered Higgins into a clinical trial that he began at Harbor in 2002, according to hospital documents and a federal database. He wrote in the protocol that he planned to recruit hundreds of patients with aortic problems and implant a Medtronic stent to determine whether it was safe and effective, including for uses regulators had not yet approved.

He recruited 303 patients for the trial over the years, according to a spreadsheet that White’s nurse gave to Ryan. Higgins was the last on the list.

Twenty years after the study began there are no published results.

Federal regulations require results to be published within a year of the trial’s completion. Those rules help protect patients from being asked to volunteer for risky experiments where results are never released and science doesn’t advance to help the public.

County officials declined to answer many of The Times’ questions. In a statement, they said they were proud of White, who was involved in early development of the stent grafts.

The statement said Ryan’s complaints were “clouded” by the fact he had earlier filed a federal lawsuit against Medtronic, claiming that he had helped invent the stent graft and that his name should have been on its patent. Therefore the patent was invalid, he claimed, and the government was being defrauded by paying an inflated price. A judge dismissed the case.

White retired in 2016 on his annual county pension and benefits of $262,000, according to government data collected by Transparent California. He continues to work as a surgeon part time at the Long Beach Medical Center.

County officials described Medtronic’s payments to the doctors as consulting fees to teach other surgeons about the company’s device — which they said was “a fairly common practice” in medicine.

Unlike most other hospitals with large research operations, Harbor does not have an institutional review board to monitor the studies. IRBs are committees in charge of protecting research subjects. Instead, Harbor and the county delegated that responsibility to the Lundquist Institute.

“The notion that Harbor’s IRB process is somehow less accountable or inferior because it is an external entity is categorically flawed,” wrote Bari Golin-Blaugrund, an executive at Actum, a consulting and crisis communications firm, hired by the county, in an email.

The county continues to allow Harbor doctors to accept large payments from medical companies.

Matthew Budoff, a Harbor cardiologist, received $558,227 in 2021 from 10 pharmaceutical companies, according to a federal database. The payments were mostly for consulting or speaking to other doctors about the companies’ new drugs.

Budoff said the database was wrong and some of that money was not paid to him directly but had gone to Lundquist to support clinical trials he worked on for the companies. While he continues to care for Harbor patients, he said, most of his time is spent on research and his salary comes from Lundquist. “I always disclose my conflicts of interest,” he said.

Some scientists have raised questions about the design and conclusion of a trial in which Budoff found the fish oil drug Vascepa worked to reduce artery plaque. They say the mineral oil he gave as placebos to patients in the control group appeared to increase their coronary plaque, leading to a false conclusion the drug worked. In an interview, Budoff said he would not have used mineral oil as a placebo had he known then about its possible adverse effects. He said no patients were harmed and that he didn’t believe the placebo had significantly changed the trial’s conclusion.

In her small living room in Silver Lake, Higgins surrounds herself with dozens of photos of family and friends. Because of the stroke, her mind still slips, she says, and the photos help her remember who they are.

The framed pictures show her life before her stroke. There was an annual rafting trip on the Kern River. She once relished taking her nieces and nephews on ski trips to Mammoth.

When a reporter visited her in June, she spoke of the 2,000 books she had collected. She pointed to one on the shelf behind her, “The Road” by Cormac McCarthy.

“Have you read this?” she asked.

“The joy of my life was reading,” she said. “Now I can’t read more than a blurb.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.