His parents died. Then Amazon fired him for seeking time off, a worker’s suit alleges

- Share via

An Amazon worker at a Bakersfield warehouse alleges the company fired him last month for seeking time off to grieve his parents’ deaths, according to a lawsuit filed Tuesday in Kern County Superior Court.

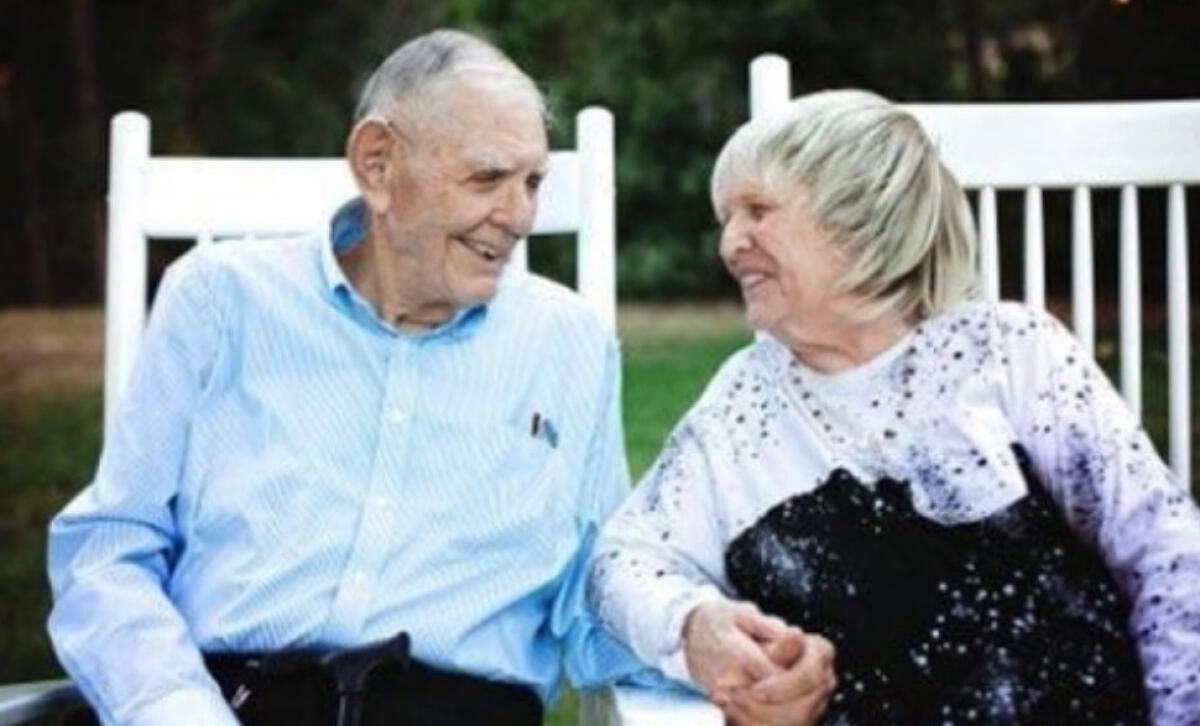

Scott Brock, who worked at Amazon’s BFL1 fulfillment center, lost both his parents, Mary Massengale Brock and Curtis Harold Brock, in late January, only six days apart, according to the complaint.

When Brock requested three additional days of bereavement leave after his father died, Amazon’s human resources department asked to see an obituary. Brock submitted the obituary for both his parents, but on Feb. 2, Amazon denied his request for time off and subsequently terminated his employment, the complaint alleges.

Brock is suing the company for wrongful termination and violating state laws protecting employee leave related to the care of family members and medical conditions.

Assembly Bill 1949, a state law that went into effect Jan. 1, makes it illegal for an employer to refuse to grant a request by an eligible employee to take up to five days of bereavement leave upon the death of certain family members or retaliate against a worker for exercising those rights.

The legislation expanded the California Family Rights Act, a law that guarantees eligible workers up to 12 weeks of unpaid, job-protected family care and medical leave.

During this month’s historic heat wave, employees at Amazon’s largest West Coast air freight facility were conducting their own workplace temperature checks.

Brock was eligible for such job-protected leave, according to the lawsuit, because he was an Amazon employee for more than a year and worked at least 1,250 hours in the 12 months before the leave.

Amazon disputes that Brock was terminated for requesting bereavement leave.

Brock was terminated as a result of an investigation that found he had threatened a co-worker in violation of Amazon’s workplace conduct policy, company spokesperson Alisa Carroll said.

“While we’re very sorry for the loss of Mr. Brock’s parents, that’s unrelated to why he’s no longer working at Amazon,” Carroll said in an email.

Carroll said the company at times asks employees for documentation of a family member’s passing when bereavement leave is requested. After he provided documentation, Brock’s bereavement leave was approved and paid, she said.

Ronald Zambrano of West Coast Trial Lawyers, who is representing Brock, said Amazon is using the argument Brock had at work “as a pretext to sanitize the termination.”

Zambrano confirmed the company paid out seven days of leave in Brock’s final paycheck, but said that doesn’t absolve the company of liability.

Brock, 53, began working the night shift at the fulfillment center in November 2021 as a “picker,” who sorts, scans and prepares packages for delivery.

Brock’s mother died Jan. 21 at age 85. On Jan. 22 he used Amazon’s AtoZ app to request four days off, the complaint said. His father died Jan. 27 at age 87, and on Jan. 29, Brock requested an additional three days off, the suit said.

In an interview, Brock said he had been trying to spread out his personal time off to visit his parents in the hospital since around mid-December.

His family had learned that doctors wouldn’t be able to operate on his father’s heart valve. The news seemed to worsen his mother’s preexisting health problems. Brock’s mother was admitted to the hospital the week after they celebrated her birthday Dec. 13, Brock said.

Harry Sentoso, 63, went back to work at Amazon as part of the company’s hiring wave. Two weeks later, he was dead from COVID-19.

But Brock said he felt as if his supervisors were trying to make it difficult for him to take time off. Brock said he repeatedly asked for what the company terms “voluntary” unpaid time off, which Amazon often offers to employees to reduce overstaffing.

“It just seemed like it turned into a game with them. Other people were given time off, but not me,” he said.

Brock said he was under stress and stretched thin at work when he had an argument with a supervisor in early January, and he was asked to stay home from work for several days. When he went back to work, he appeared to be in good standing, Brock said.

Brock said that when he did not show up to work Jan. 29, his employee profile flagged he had used more unpaid time off than he was permitted to take. Brock said he went in to work to show the human resources department his parents’ obituary. There, Brock said, he was provided an email address to send the obituary to.

Soon after he provided the obituary, he received a phone call from a human resources representative who told him the decision had been reversed, and his second bereavement request had been approved, Brock said. But on Feb. 3, he received an email giving notice of his termination. The notice, reviewed by The Times, did not specify a reason for Brock’s termination.

Attorney Zambrano called the case “heartbreaking” and said his client was just the “latest of many victims” of Amazon’s human resources practices.

The company has long been under scrutiny over allegations of harsh, algorithm-led work quotas, high injury rates and retaliatory firings — which California lawmakers aimed to crack down on in 2021 legislation, AB 701.

The pandemic exposed how the company’s metric-reliant employee apps resulted in erratic notifications, incorrectly revoked or delayed benefits, and haphazard terminations.

Amazon and Whole Foods warehouse workers received COVID exposure notifications, The Times found in 2020, through a patchy automated text and robocall system that issued notifications out of order or seemingly at random, alerting some workers but not others.

A man at an Irvine fulfillment center died two weeks after being called back to work during Amazon’s coronavirus hiring spree, The Times reported in 2020. Then, Amazon human resources representatives repeatedly called to ask where he was, even after the man’s family explained that he had died.

The lawsuit seeks a jury trial and monetary relief for general, consequential and special damages in the form of earnings losses, physical sickness, emotional distress and future medical expenses. The complaint also seeks punitive damages for the company’s “conscious disregard of plaintiff’s rights.”

Brock, who lives in north Bakersfield, is the youngest of five; he and his two brothers and two sisters had been coordinating hospital, and later, hospice care for their parents, as well as the sale of their parents’ mobile home at Kern Canyon Estates in east Bakersfield.

Brock said he had been helping move out his parents’ belongings on the days for which he had requested bereavement leave.

A memorial service at the church Brock’s parents attended is scheduled for Saturday, which would have been their 65th wedding anniversary.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.