Column: These companies cynically used global crises to juice profits — and brought us inflation

- Share via

Throughout all the debate in the last year over what has caused higher prices and how to remedy them, one term hasn’t received the attention it deserves, given how well it explains the trend:

“Greedflation.”

The term defines as what happens when businesses raise prices higher and faster than is needed to cover increases in their costs. We’ve reported before that soaring corporate profits have contributed more to inflation than the Federal Reserve Board’s preferred targets, wages and consumer demand. Two recent papers, however, measure their impact and identify some of the leading culprits by name.

Until recently it was considered heretical to point to a possible relationship between the first signs of a profit explosion and sharp price increases.

— Weber and Wasner, University of Massachusetts

Researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City calculated that in 2021, when inflation reached an annualized rate of 5.8%, corporate markups grew by 3.4%. The upshot: Markups “could account for more than half of 2021 inflation.”

In other words, during a period in which consumer demand largely cratered because people were staying home, businesses jacked up prices so far and so fast that they more than compensated for the decline in overall sales.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

That’s the finding of the second paper, by Isabella M. Weber and Evan Wasner of the University of Massachusetts Amherst. They traced price increases at several companies and connected them with their executives’ public indications that the pandemic, along with oil price shocks resulting from the Russian invasion of Ukraine and supply logjams at American ports, gave them headroom to raise prices without a significant backlash from consumers.

Once publicity about higher inflation percolated through news reports, consumers came to expect higher prices, which were blamed more on the headlined inflationary factors than on businesses’ inclination to protect or even increase their profit margins.

“Publicly reported supply chain bottlenecks and cost shocks,” Weber and Wasner wrote, “serve to create legitimacy for price hikes and create acceptance on the part of consumers to pay higher prices.”

What Weber and Wasner labeled “sellers’ inflation” has posed problems for the Fed’s effort to bring inflation down that the central bank has never adequately confronted. The run-up in prices instituted by big corporations, the authors wrote, prompted workers to demand higher wages; amid a labor shortage, wages indeed rose — for a time.

Economic growth will be a victim of the banking crisis, the Fed says, but will it be enough to quell inflation?

The Fed tried to combat the recent inflationary surge with tools that had been developed for more conventional inflationary cycles. In those cycles excess demand forced prices higher; therefore tamping down demand by raising interest rates has been a customary remedy. That’s been the strategy of the Fed over the last year, during which it has raised rates by a full five percentage points.

But that has only further victimized those harmed most by inflation: workers. “Ultimately,” write Weber and Wasner, “hiking interest rates is meant to increase unemployment, which hurts workers who have already been in a defensive position in this inflation.”

The Fed has tended to downplay the role of corporate profit-seeking in driving inflation. “Until recently it was considered heretical to point to a possible relationship between the first signs of a profit explosion and sharp price increases,” Weber and Wasner observe.

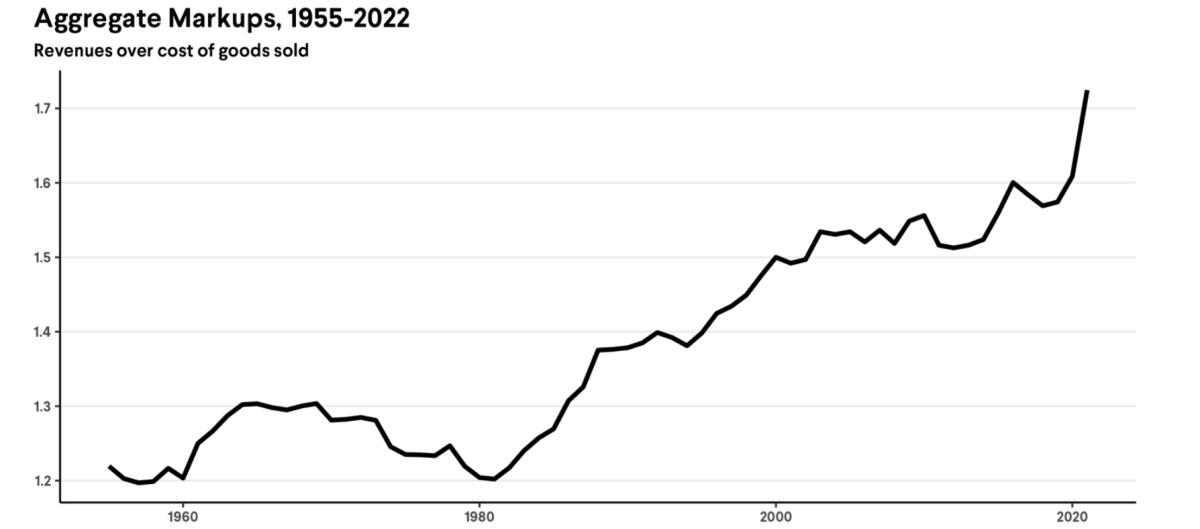

Yet the extraordinary increase in corporate profits has unfolded in plain sight. Since the dawn of the 21st century, wages have gained 82%. Corporate profits have soared by nearly 600%. Corporate markups — that is, prices over costs — spiked much higher than historical averages. “Between 1960 and 1980, markups averaged 26% above marginal costs,” Joseph E. Stiglitz and Ira Regmi of the Roosevelt Institute noted in December. “The average markup charged in 2021 was 72% above the marginal cost.”

During the pandemic, corporate chief executives have been unabashed about disclosing their pricing strategies and tying them to the inflationary atmosphere.

As PepsiCo Chief Financial Officer Hugh Johnston told investment analysts in April 2021, “the environment is well set up for pricing to be positive going forward.”

At the giant food processing company Tyson Foods, executives were equally confident in May 2021 that consumers would stay docile. Responding to a Wall Street analyst’s question about how the company would manage through a “very inflationary” environment, Chief Operating Officer Donnie King said that Tyson’s customers “certainly understand the inflationary need,” adding, “I think we will be quite successful in this endeavor” — that is, responding to inflation with price hikes.

Tyson, indeed, was able to fatten its profit margins through price increases that more than compensated for lower sales volumes during the pandemic. In the fourth quarter of 2021, its sales of beef fell by 6.2% compared with the same period in 2020, but it raised prices by 31.7%, enabling it to widen its operating margin on beef to 19.1% from 13.2%.

In the case of chicken, sales grew only 3.6% from the fourth quarter of 2020 to the same quarter a year later, but Tyson raised prices by 19.9% — turning a negative margin of 7.6% at the end of 2020 to a 3.6% profit a year later.

Another company that bobbed atop the inflation wave through higher prices was Procter & Gamble, which markets such familiar products as Pampers diapers, Bounty paper towels, Gillette razors, Head & Shoulders shampoo and Crest toothpaste. In the fourth quarter of 2022, sales across all P&G’s product segments fell by 6% compared with a year earlier, but it raised prices by 10%, limiting its overall decline in profit margin to 1.6 percentage points.

A year later, its pricing strategy bore even greater fruit: Sales volume had shrunk by 3% year to year, but thanks to another 10% average price increase, its profit margin widened by 1.5 percentage points to a healthy 48.2% of net sales.

The chemical giant DuPont was candid about how the supply logjam and other shocks enhanced its ability to raise prices and make them stick.

Despite pandemic closures and more shareholder votes against their pay, CEO compensation keeps soaring. But there are signs the backlash is working.

“It’s a constructive market for pricing,” Chairman and CEO Edward D. Breen said in February 2021. DuPont’s chief financial officer, Lori Koch, referred to cost increases in raw materials in adding, “there’s ... a couple of recent force majeures in the industry that’s making the price environment even more conducive.”

Asked if a decline in raw material prices would prompt DuPont to roll back its prices, Breen said not to worry. “If a recession hits, and commodity costs come down,” he said, DuPont’s intention would be “maintaining more price than the decrease on the commodity.”

Oil companies were especially adept at extracting profits from the volatile pandemic-era markets, largely because they’ve operated amid sharp run-ups and declines in oil prices for many decades.

When demand all but disappeared in 2020 and world oil prices collapsed, Exxon Mobil and Chevron, among other oil companies, shut down their least profitable production facilities, as they had done in the past. But when demand began to recover in 2021 and oil prices spiked with the Russian invasion of Ukraine in early 2022, they were slow to scale production back up.

“We’ve created this hole with a lot more capacity coming off-line without a whole lot of new capacity ... coming on,” Darren Woods, chairman and chief executive of Exxon Mobil, said last July. “So we’ve got this gap, ... which has led to a record, record-high refining margins.” Woods said that new refining capacity had been delayed by the pandemic and the poor economics of oil product in 2020 and early 2021, and would soon appear.

Corporations’ ability to put through price increases derives from more than consumer docility. Those with strong brands, a reputation for quality, and products seen as indispensable will typically find it easier to retain customers.

Corporations are raising prices at the fastest rate since 1955, driving inflation higher.

That’s the explanation offered by Procter & Gamble CEO Andre Schulten to investors last July: “Our categories being daily-use categories that consumers don’t deselect even when they see high levels of inflation, our focus on Irresistible Superiority, our ability to make strong value claims based on that superiority ... positions us well to compete in the environment.”

Another factor is a dearth of competition. “Companies are not raising prices solely because of the increasing costs of supplies and components and of labor,” former Labor Secretary Robert B. Reich told a House committee on May 7, 2022. “They’re passing these costs on to consumers in the form of higher prices ... because they can. And they can because they don’t face meaningful competition.”

Since the 1980s, Reich testified, “two-thirds of all American industries have become more concentrated.” That allows them to raise prices “without risking the possibility of losing customers, who have no other choice.” For businesses in this enviable position, publicity about inflation gives them cover to raise prices and funnel the gains into greater profits.

Nor should anyone expect price reductions as costs come down. Corporate executives have generally signaled that they expect price increases they have already instituted to remain in place.

If one properly acknowledges the contribution of corporate profit-seeking in inflation, two things become clear. One is that the Fed has grasped the wrong end of the stick in its battle against high prices. That may not be surprising, because monetary policy is the only tool the Fed possesses.

Another is that corporations’ price-setting powers are the result of policy choices by successive congresses and administrations. They’ve stood idly by as mergers and acquisitions reduce competition throughout the economy and have allowed companies in some industries to collect windfall profits without limitation.

Stiglitz and Regmi see some glimmers of hope that decades of indulging big business may be reversing. Under Chair Lina Khan, the Federal Trade Commission has signaled a more aggressive stance against anticompetitive mergers. The Inflation Reduction Act enacted last year incorporated new incentives for production of renewable energy sources, which could counteract the market power of big oil companies. Providing child care and raising wages would bring more people into the labor force.

But America is still big business’ playing field. For even longer than the last year we have been paying the price.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.