Disasters like Hilary are a magnet for fraudsters. Look out for these scams

- Share via

If you live in the path of Tropical Storm Hilary, you may soon hear from people offering you the help you desperately need. And the rest of us are probably already being contacted by organizations raising money for disaster victims here, in Maui and in other wildfire-wracked communities.

Unfortunately, some of the outreach will come from people who want to harm, not help.

Online scammers are eager to take advantage of people’s need for aid, as well as their desire to help. Using the internet’s ability to conceal their true identity, they pose as government officials, charities and community groups as they try to collect money or sensitive personal information they can sell online.

Here are some tips from security experts about how to protect yourself from scammers trying to compound the misery caused by fires and floods.

Flood damage isn’t covered by homeowners insurance. Here’s what you can do in the wake of Hilary, the first tropical storm in Southern California in 84 years.

FEMA and emergency aid scams

When a natural disaster strikes, the governor of a state can ask the federal government for help. If the president agrees and declares a major disaster or emergency, a range of federal programs become available to match the nature of the disaster.

As of Monday afternoon, President Biden had not declared a disaster or emergency in response to Tropical Storm Hilary. So that’s the first reason to be suspicious of calls, texts or emails from anyone claiming to be from the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

Even if FEMA were activated and aid authorized, it’s important to remember how the process works. The agency provides money and services to people in the area covered by the disaster or emergency declaration whose property has been damaged and whose losses are not covered by insurance, FEMA says, but “in every case, the disaster victim must register for assistance and establish eligibility.”

In other words, you’ll have to apply for help. FEMA won’t call and offer it to you. Nor will a government official call out of the blue and ask for sensitive personal information (such as your Social Security number and banking information) in the guise of determining your eligibility, arranging your payment or scheduling a property inspection. If you get a request like that, it’s a red flag.

(If and when a disaster is declared, you can apply for FEMA assistance through DisasterAssistance.gov, through the FEMA mobile app or by calling the FEMA Helpline at 800-621-3362. To use a video relay service, captioned telephone service or other communication services, FEMA says you’ll need to provide FEMA the number assigned for that service.)

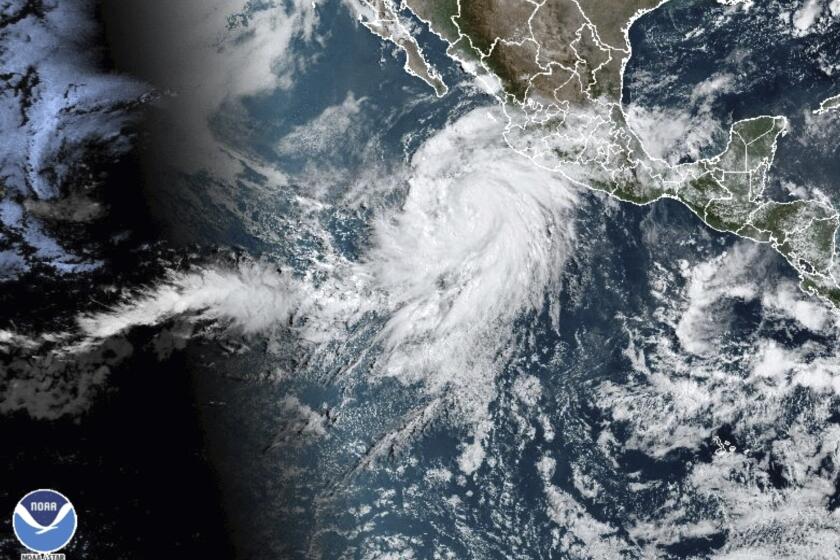

After days of urgent warnings, Tropical Storm Hilary made landfall in Baja California on Sunday, turning roads into rivers and imperiling homes before barreling north toward Southern California.

FEMA Press Secretary Jeremy Edwards said the agency does make calls “to survivors who have already applied for assistance to provide updates on the existing application.” But again — that’s after you’ve applied, not before.

The Federal Communications Commission put it this way: “First, know that officials with government disaster assistance agencies do not call or text asking for financial account information, and that there is no fee required to apply for or get disaster assistance from FEMA or the Small Business Administration. Anyone claiming to be a federal official who asks for money is an imposter.”

Don’t trust your caller ID to ferret out fakes, either, the commission warned. “Phone scams often use spoofing techniques to deliberately falsify the information transmitted to your caller ID display to disguise their identity or make the call appear to be official,” it said.

If you get a call from someone claiming to be working for a government agency, the FCC says you should just hang up and call the number on the agency’s website. “Never reveal any personal information unless you’ve confirmed you’re dealing with a legitimate official,” the commission said, adding, “Workers and agents who knock on doors of residences are required to carry official identification and show it upon request, and they may not ask for or accept money.”

In a statement, Edwards said that “FEMA recently launched a rumor control and frequently asked questions web page to keep survivors of the Hawaii wildfires aware of rumors and scams, and to help them better understand the federal disaster assistance programs and processes.” The agency has also posted a public service announcement to its YouTube channel “to reach survivors in as many ways as possible,” he said.

An unprecedented tropical storm watch has been issued for Southern California as Hilary barrels north toward the United States.

Scam fundraisers for disaster victims

The other side of the disaster-scam coin is fraudsters seeking money under the pretext of helping people who lost homes or loved ones. They’ll often pose as representatives of familiar charities, making difficult-to-detect changes to the name and web address to add authenticity.

Another common tactic is creating fake crowdfunding campaigns on sites such as GoFundMe to help disaster victims, then promoting them on social media. That’s why it’s important not to post pictures on social networks of friends or family members and their damaged property — scammers will use those to create bogus crowdfunding campaigns, collecting money that the actual victim will never know about, said Ally Armeson, the Executive Director of the nonprofit Cybercrime Support Network.

The key to protecting yourself, Armeson said, is to research any group that asks for a charitable donation.

The FCC advises, “Always verify a charity’s legitimacy through its official website.

“If the only thing you’re finding online is the [web page] of the fundraiser, that’s a red flag,” Armeson said.

If you have doubts, the FCC advises checking with Better Business Bureau’s Wise Giving Alliance, Charity Navigator, Charity Watch, or GuideStar.

Armeson’s hard and fast rule: Never give money through a link in an unsolicited email or text, or over the phone on an unsolicited call. That’s a good way to load malware onto your computer or phone, in addition to being scammed.

“If someone is contacting me about [making a donation], I double check it every single time. If it’s the president of the United States, if it’s my mother, I check it every single time,” Armeson said.

“I’m not saying wait days. Just take 10 to 20 minutes. If it’s a scam, if it’s not legit, you’ll see it in that 10 to 20 minutes.”

Andrew Gardner, vice president of research, innovation and AI at Gen, offered this suggestion via email: “People looking to donate to disaster relief funds should seek out opportunities to give directly to well-known charities.” He urged people to find the website or phone number of a major charity by searching for it online rather than following a link provided in a text or email.

Scammers will typically rush you to make a decision — the sense of urgency blunts your critical thinking powers. But “you have to slow down and say, is it more important that I help quickly or that I help effectively?” Armeson said.

The Federal Trade Commission also says to beware if someone thanks you for a donation you didn’t make. That could be a trick to prompt you to give to a bogus site.

One more red flag from the FTC: “Scammers make lots of vague and sentimental claims but give no specifics about how your donation will be used.”

Scam emails often originate outside the United States, and bad grammar, spelling and syntax employed in the name of a major federal agency or charity are a dead giveaway of a scam. But those mistakes may be a thing of the past thanks to ChatGPT and its ilk, Armeson said.

“With generative AI now basically accessible to all of us, you can use generative AI to create a compelling, professional message that can be used in an email” or the script for a phone call, she said.

The first tropical storm to hit Los Angeles in 84 years dumped record rainfall and turned streets into muddy, debris-swollen rivers.

How to report fraud

If you come across a scam related to a natural disaster, you can report it to any or all of these agencies:

- The U.S. Department of Justice’s Disaster Fraud Hotline at www.justice.gov/DisasterComplaintForm or 866-720-5721

- The FTC at ReportFraud.ftc.gov

- The FCC at ConsumerComplaints.fcc.gov

- The California Attorney General’s Office at oag.ca.gov/charities/complaints

- The FBI at tips.fbi.gov

- If the fraud took place online, the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center

About The Times Utility Journalism Team

This article is from The Times’ Utility Journalism Team. Our mission is to be essential to the lives of Southern Californians by publishing information that solves problems, answers questions and helps with decision making. We serve audiences in and around Los Angeles — including current Times subscribers and diverse communities that haven’t historically had their needs met by our coverage.

How can we be useful to you and your community? Email utility (at) latimes.com or one of our journalists: Jon Healey, Ada Tseng, Jessica Roy and Karen Garcia.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.