8 to 3: Why summer school won’t guarantee a successful fall

- Share via

This is the July 12, 2021, edition of the 8 to 3 newsletter about school, kids and parenting. Like what you’re reading? Sign up to get it in your inbox every Monday.

With coronavirus numbers creeping up, online learning in flux and public health departments revising their return-to-campus guidelines almost week by week, parents, educators and experts are increasingly turning to summer school to try to figure out fall.

Will kids come back? Will they be able to learn in a group? What about the Delta variant? Is that more likely to spread when unvaccinated kids return to their classrooms?

These are hugely significant questions. But anyone who tells you it’s possible to extrapolate the answers from summer school is lying.

For one thing, the data we have are mushier than a banana at the bottom of a paper bag lunch. California districts have pumped metric tons of cash into summer school programming, in many cases extending the term and the hours per day, as well as opening summer classes and on-campus child care to all students for the first time.

But the Los Angeles Unified School District and other large districts across the state have been selective and limited in what they will say about how many kids are attending, where they’re attending, in what format, or how those numbers compare to previous years.

“We didn’t really have expectations of attendance this year, given how unprecedented all the circumstances are,” said Laura Beebe of the nonprofit after-school program L.A.’s Best, which is running extended care at about 200 LAUSD elementary schools this summer. “It’s not a typical summer, so we can’t compare it to summer 2019.”

To be frank, a lot of folks think we can and should compare this year with that one — but LAUSD has so far declined to share its 2019 numbers. In other districts that have shared data publicly, the number of kids attending in person is essentially flat. There are several reasons this could be happening — I’ll go through some of them below — but anyone watching with an eye toward fall might rightly be anxious.

That’s because most large districts have committed to a remote learning option for the fall, when school funding will once again be tied to in-person attendance.

To be sure, a plurality of California parents say they want remote learning to remain as an option, even if they prefer that their own children learn in person. There are students who thrived under remote instruction, and those whose underlying medical conditions make it dangerous for them to return until most kids are vaccinated. The need is obvious.

But right now, about half of LAUSD summer school students are attending remotely. And if that number holds — which, again, is not something we can necessarily extrapolate from the data we currently have — it could create unexpected hurdles going forward.

So why aren’t there more kids on campus this summer? Without solid data, especially geography and demographics, it’s just really hard to say. But anecdotal evidence and a bit of mom-sense can tell us a lot about what might be happening.

First, the same parents who were stressed about safety in the spring are still stressed about it now. The ascendency of the Delta variant and the whiplash rules around masking and distance may actually have increased anxiety. And parents who may have lost or left work to manage their children’s remote learning may not be especially incentivized to leave their children in someone else’s care before enhanced benefits expire in September.

“It’s the same thing we faced in the spring,” said Julie Marsh, professor of Education Policy at USC’s Rossier School of Education. “They might be concerned about social-emotional well-being, and they’re probably really concerned about whether schools are [a safe] place to be.”

Second, the summer is not the fall: The hours are typically worse, the location is usually less accessible, and most working parents are used to paying out of pocket for care. Although free care and learning are available to more kids on more campuses this term, it’s not clear how many families know that, or were able to plan around it.

“I just don’t think there was enough time to plan and effectively implement both summer school and the school site programs they’re sponsoring,” said Mike Lansing, executive director of the Boys & Girls Clubs of the Los Angeles Harbor, which runs several school sites in addition to its own summer program. “With it rolling out late and all those limitations, I think a lot of families decided against it.”

This may be particularly true for kids whose siblings don’t go to school with them, since summer options outside LAUSD are still pretty pinched. If you’re already providing care for one child at home, it doesn’t necessarily make sense to arrange outside care for another.

But the most significant factor may be that parents simply don’t want kids in school right now. No matter how much social-emotional curriculum is built into summer learning, it’s still classrooms and teachers and books. And despite widespread fear about learning loss, there’s good evidence to suggest academics just aren’t appealing to parents right now.

“I have five school sites we’re supporting right now, along with seven club sites, and our club sites have much higher attendance than our school sites,” despite serving the same population in the same area, Lansing told me.

What makes this more striking is that the school sites actually offer longer hours this year.

“It’s limited what you can do on a school site,” Lansing explained. “There’s a lot more we can do at our club houses.”

Marsh, the professor, agreed.

“Parents are deeply concerned about the impact the pandemic has had on kids’ well-being, beyond their academic well-being,” she told me.

So why are we so hung up on summer school? Most kids never went there anyway — in LAUSD, most weren’t even eligible until this year.

The numbers also mean very little if we don’t know who is attending, and where. Beebe told me we do know that some schools are full, while others are empty. If those patterns mimic the ones we saw in the spring, when wealthier, Westside schools dominated the return to campus in Los Angeles, it would tell us a lot more about what to expect in August than a raw numerical comparison — which, to be clear, we also should have.

“Social interaction is a challenge for kids who’ve been home,” Lansing explained. “That’s going to be a big challenge when schools reopen in August, because kids have not been in that environment for 18 months.”

Don’t toss that mask yet

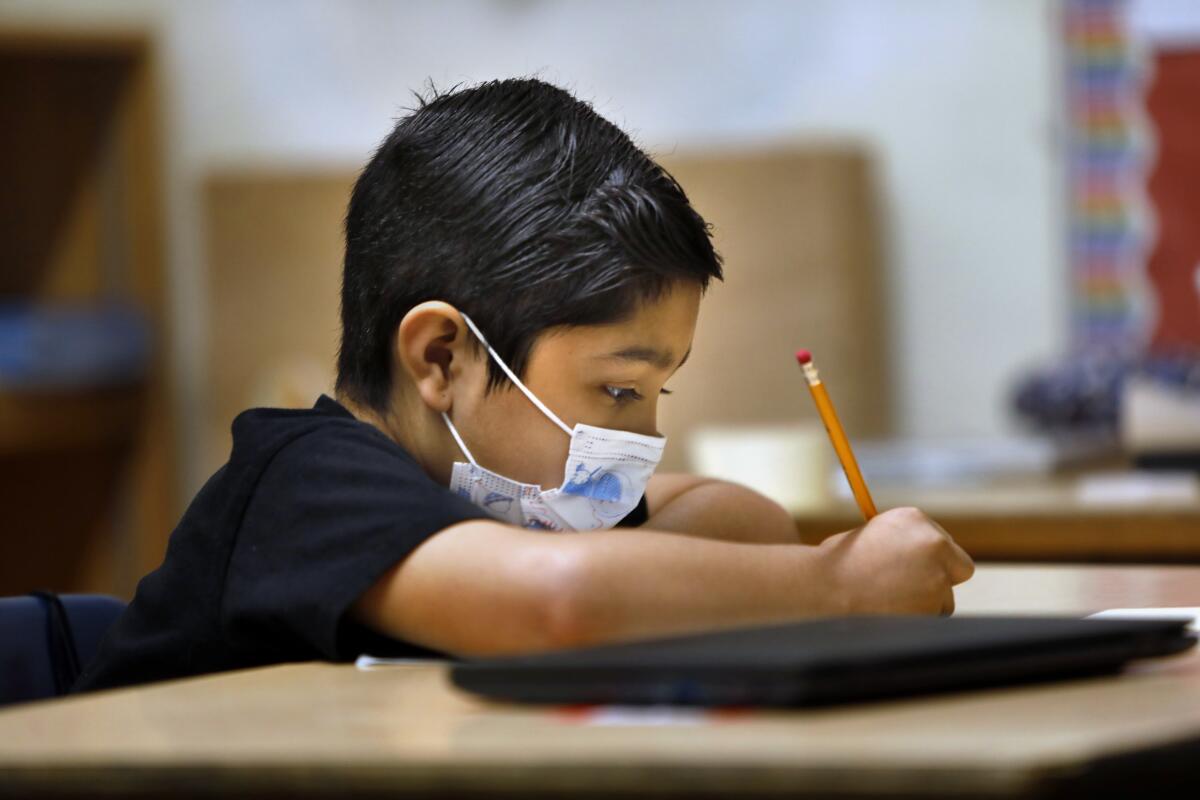

Overall, California has taken a pretty cautious approach to COVID-19 in schools, and that will continue this fall. State officials announced Friday that the new school year will start with students and teachers wearing masks. “Students should be able to walk into school without worrying about whether they will feel different or singled out for being vaccinated or unvaccinated,” California Health and Human Services Secretary Mark Ghaly said. Here’s the story from The Times’ Colleen Shelby and Howard Blume.

Parents don’t entirely agree with Ghaly’s last point about vaccinations, incidentally. In a recent statewide survey, more than two-thirds of parents said that students should be required to get a COVID-19 vaccine once it has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration, with exceptions for medical reasons. But, as my colleague Melissa Gomez reported, the parents did overwhelmingly support the state’s decision to return to in-person instruction in the fall.

Enjoying this newsletter?

Consider forwarding it to a friend, and support our journalism by becoming a subscriber.

Did you get this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up here to get it in your inbox every week.

Power Girls, transitional kindergarten and more

Getting back to school won’t be easy for everyone. The pandemic has been a traumatic event for almost everyone, and in some ways has been especially tough on children. Schools are going to have to learn how to recognize and treat trauma in both students and teachers, some experts say. KQED’s Mind/Shift.

Ella Acker started the Power Girls Summer Camp in Marin County four years ago — which might not seem so extraordinary until you realize that she is only 18 now and graduated from Archie Williams High School in San Anselmo just last month. Her goal: to mold strong, confident girls, in part by giving them the tools to build up each other. Marin Independent-Journal.

Here’s a look at how California’s new transitional kindergarten will be rolled out. EdSource.

Once upon a time, the tiny Belridge Elementary School District in Kern County had resources that other districts could only dream of. The reason? Its budget was tied to production in the surrounding oilfields, and business was good. That hasn’t been the case so much lately — so much so that Belridge closed shop at the end of last month and was absorbed into the neighboring McKittrick Elementary School District. Bakersfield Californian.

Finally, there’s this: Santa Clarita’s Hart High School is wrestling with the same conundrum that faced Stanford University and professional sports franchises in Washington and Cleveland — what to do about a team name that many people view as racist. Since 1946, Hart High’s mascot has been the Indians. This week, after months of debate, the local school board is scheduled to make a decision about whether to adopt a new character. Los Angeles Daily News.

I want to hear from you.

Have feedback? Ideas? Questions? Story tips? Email me. And keep in touch on Twitter.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.