L.A. says it got 21,631 homeless people into housing. Is that really true?

- Share via

In the pervasive gloom that has surrounded the results of L.A. County’s annual homeless count, officials have repeatedly pointed to one bit of bright news: A record number of people got off the streets and into housing last year.

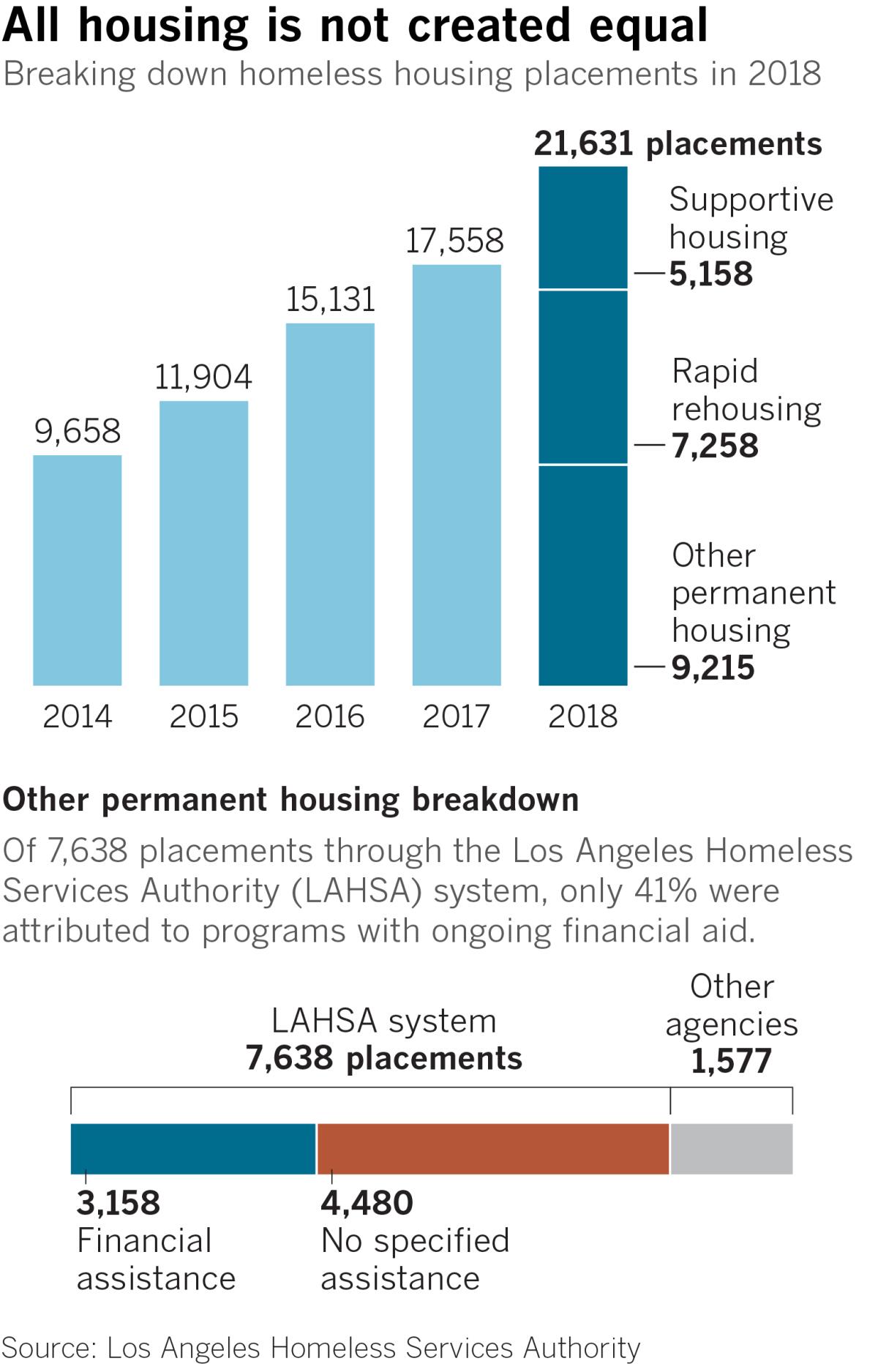

The 21,631 people who were housed last year using millions of new tax dollars was 23% higher than in 2017 and double the number housed in 2014. Still, the population living on the streets, in vehicles and in shelters climbed 12% in the past year, putting the number of homeless people at nearly 59,000 countywide.

“Had we not housed them it would have looked much worse,” Peter Lynn, executive director of the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, said in a briefing with The Times.

But a breakdown of that number obtained by The Times shows a much more complicated picture of who gets housed and how.

Only about a quarter of the nearly 22,000 people housed last year received “permanent supportive housing” — government-subsidized apartments with services meant for people who have been homeless for more than a year and have physical or mental complications.

In addition, 7,258 were given temporary subsidies for “rapid rehousing” and 9,215 — or 42% of the total — were listed in a catch-all category called “other permanent housing.”

The homeless authority did not immediately provide details on the “other permanent housing” category when The Times requested it. But after reviewing its numbers, the agency produced a breakdown two weeks later.

It showed that thousands of people obtained housing largely by themselves, with only a kickstart from the government-funded homeless services system. Many of those people are living in circumstances that could be considered fragile.

More than 4,400 of all those housed either roomed with friends or relatives, found rentals they could afford or, in a few cases, were able to return to where they lived before.

However, the homeless authority counted them as “placed” by the system because they received assistance that could — but did not always — include one-time financial aid, such as a security deposit for moving in or the activation fee for a utility.

“Generally speaking, they got some kind of help,” Lynn said. “It might have been just housing search and location as well as financial assistance.”

Another 1,300 homeless people went to a variety of destinations, including board and care homes, public housing projects, single-room-occupancy buildings and nursing homes.

Once those people were housed, the agency had no further contact with them. Unless they come into contact with outreach workers and are re-entered into the countywide homeless database, Lynn said, the homeless authority assumes they are still housed.

According to a statistical estimate produced by the homeless authority as part of this year’s survey of the homeless population, about 27,000 people lost their housing during the year and obtained a new home outside of the homeless services system.

There is no way to gauge how many of those aided by the system might have found new housing without that assistance.

Lynn said the number would probably be low because of recent evidence that people who lose their housing are getting stuck in homelessness longer.

Placements in rapid rehousing — about a third of all of those reported as housed — also included an unknown percentage of people whose housing status could be unstable or may already have changed.

The rapid rehousing program provides temporary rental assistance to people who become homeless because of a crisis and are considered capable of becoming self-sufficient again. They receive subsidies starting at 100% of their rent and diminishing over time until they expire after a year to 18 months.

About half of the more than 7,000 housed through rapid rehousing were still receiving subsidies. Early experience with the program in Los Angeles County suggests that the dropout rate has hovered around 20%, although the percentage who have moved onto permanent housing has not yet been rigorously documented.

“Some number will not use rapid rehousing to move into permanent housing,” Lynn acknowledged. “We don’t have the information about where they went.”

Among the half who have successfully exited the program, an additional 7% are expected to lose their housing again.

There is no system to track participants after they leave. The homeless authority derives that figure from the number who later reenter the homeless services system.

“For this population, we think that’s a pretty good marker,” Lynn said, arguing they are people who have been helped once and so would likely seek help again.

In contrast to the other categories, permanent supportive housing provides a rental subsidy and case management or other services for as long as the recipient needs them. It is meant for the most severely impaired who are unlikely to get off the streets without long-term help.

According to the homeless authority, 4,900 permanent supportive placements went to chronically homeless people, defined as being homeless repeatedly or for more than a year and impaired physically, mentally or by substance abuse. But the resources were far from adequate.

The number of chronically homeless people in L.A. County increased by nearly 2,500 last year, as people who were newly homeless in 2017 languished on the streets or in shelters.

Many of the placements were made in market rentals supported by federal or local subsidies. Residents of those units, scattered around the county, receive services from case managers who travel to their appointments by car.

The supply of units in apartment buildings dedicated to supportive housing is limited by the pace of construction of new projects financed by tax credits and other local, state and federal funding. Historically, about 300 units of new housing are produced annually in the city of Los Angeles.

A dramatic increase in the supply is coming, but not right away. About 2,000 new units being built with financing from Proposition HHH, the city’s 2016 homeless property tax measure, are due to open next year and a similar number every year for years to come.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.