Displaced tenants got a rare right to return. Now they say there’s a catch

- Share via

When Los Angeles leaders gave the green light for Crossroads Hollywood — a new development with a hotel, shops and more than 900 units of housing — they got the real estate developer to make an unusual pledge.

Tenants whose buildings would be torn down to make way for the soaring towers in Hollywood would have a chance to return and live in the new buildings. And they would pay no more than they would have if their existing apartments, which fall under city rules that limit rent hikes, were still standing.

L.A. leaders approved the $1-billion development over the vehement objections of the AIDS Healthcare Foundation, which sued the city over the project. In the meantime, scores of tenants still living at the apartment buildings started negotiating over their “right to return.”

Now, with a deadline looming, many tenants say that Harridge Development Group is offering them a deal they do not want to accept. Among the conditions that worry them: They must agree not to make any “derogatory, critical, diminuitive, deprecating, or discrediting comments” about the building owner — or even about the deal itself.

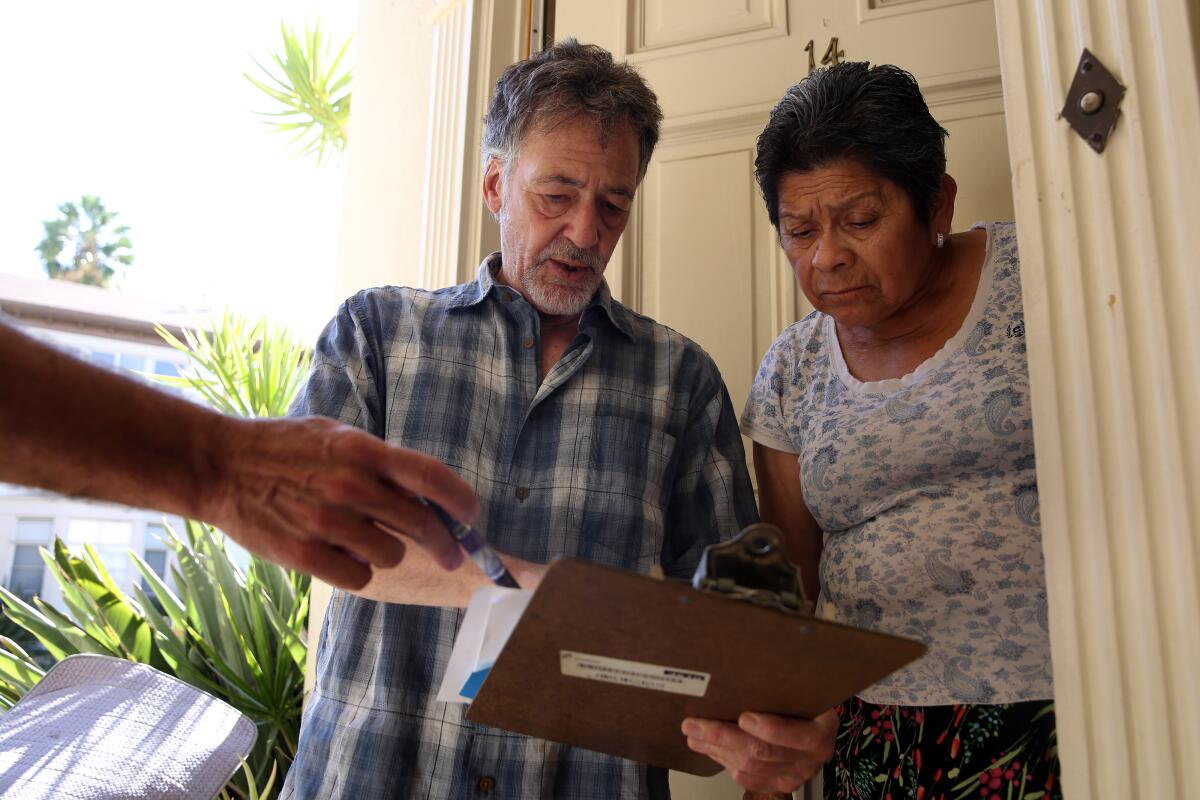

“I want to come back,” said Daniel Hernandez, a restaurant manager who has lived in the apartment complex along Selma and Las Palmas avenues for roughly a decade.

But being able to speak up, Hernandez said, “is one of our rights. That’s the Constitution!”

Such “right to return” agreements with tenants remain rare, but some L.A. developers have dangled the offer to ease concerns at City Hall about tear-downs driving out poor tenants as new buildings replace older, rent-stabilized apartments.

Harridge representative Kyndra Casper said that they were honoring their commitment, which was a “voluntary offer” made at the request of City Councilman Mitch O’Farrell. The idea they were “somehow attempting to unduly burden the tenants in taking advantage of this offer” was “simply untrue,” she said.

“If tenants intend to return to the project, we are simply asking them to not do anything that could jeopardize or impede our progress,” Casper said.

At a Wednesday meeting at a Hollywood church, Hernandez and other members of the Crossroads Tenants Assn. listened as attorney Amanda Seward urged them not to sign the return agreement. The tenants, Seward argued, do not have to be “silenced” to exercise their right to come back, since it was enshrined in the city conditions for the new project.

In an email, Seward said that the Crossroads deal is a test of whether the “right of return” offered by city leaders is a genuine effort to address the displacement of longtime renters — or “a simple gimmick that allows the developers to go forward with little chance that the displaced will realistically return.”

Under the city conditions for the new development, Harridge has to get written approval for its “first right of refusal plan” from the office of Councilman O’Farrell, who represents the Hollywood area. O’Farrell spokesman Tony Arranaga said that their office had approved that plan, calling the chance to return “a unique opportunity.”

The councilman “is concerned about the loss of rent-stabilized units, which is why he ensured that current residents were given the first right of refusal to return to a new unit” once the development is built, Arranaga said.

Arranaga added that under the deal, some tenants who qualify for affordable units set aside in the building for “very low-income” households might even end up with lower rents, in the future, than they would have had if their apartments had remained standing. The project includes more than 100 units of affordable housing — more than the 82 rent-stabilized units being torn down.

In light of that, Arranaga said, “we’re curious why anyone would want to disparage the project and pose a potential roadblock to build affordable housing.”

Seward said the displaced tenants had been trying to negotiate better terms, including more money to relocate than was legally required, so that poorer residents would be more likely to remain in the city during construction and ultimately return.

But Seward said that as they neared a deal, Harridge cut off negotiations over the terms, saying that it was contingent on the AIDS Healthcare Foundation litigation being dropped, even though “they knew the tenants had nothing to do with that lawsuit.”

AIDS Healthcare Foundation attorney Liza Brereton said that the foundation had discussed dropping its suit if the tenants were “given a meaningful right of return option,” among other protections. The group lost its lawsuit over the project in July, then filed a new lawsuit in August accusing the city of breaking the law when it approved several projects in Hollywood, including the Crossroads project.

Casper said that tenants had only been offered “additional considerations” beyond the basic right to return because the foundation had suggested it would drop the suit if they did. Negotiations between the owner, developer and tenant ultimately broke down over multiple issues, Casper said, including tenants wanting to be able to “sell their right of return to unrelated parties.”

Darrin Wilstead, executive director of the Crossroads Tenants Assn., said they had not pushed for such a provision, although they had asked at one point about relinquishing the right of return for more relocation money. Seward said that the deal that was ultimately handed to tenants lacked benefits they had fought for and included “ridiculously draconian provisions.”

“They’re looking for a way to weasel out,” Wilstead said.

In a letter to an O’Farrell aide, Seward laid out a dozen concerns with the agreement. For instance, she said she was concerned that the deal could be terminated if the landlord is “instituting an unlawful detainer action.” That language, she argued, could mean tenants lose their rights to return if the landlord tries to evict them, even if the owner doesn’t ultimately succeed in court.

Casper disagreed, saying that the clause simply clarifies that the landlord can evict tenants for lease violations, just like any other landlord, and that merely initiating the eviction process would not eliminate the right to return.

The tenants were told that they have until Friday to return the disputed agreement. Hernandez was anxious about what lies ahead as he returned home from the tenant meeting. He hasn’t started searching for another apartment, he said.

“Nothing is affordable in L.A. compared to this,” Hernandez said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.