She was hanged in California 168 years ago — for murder or for being Mexican?

- Share via

DOWNIEVILLE, Calif. — The young Mexican woman walked to her death with a firm step.

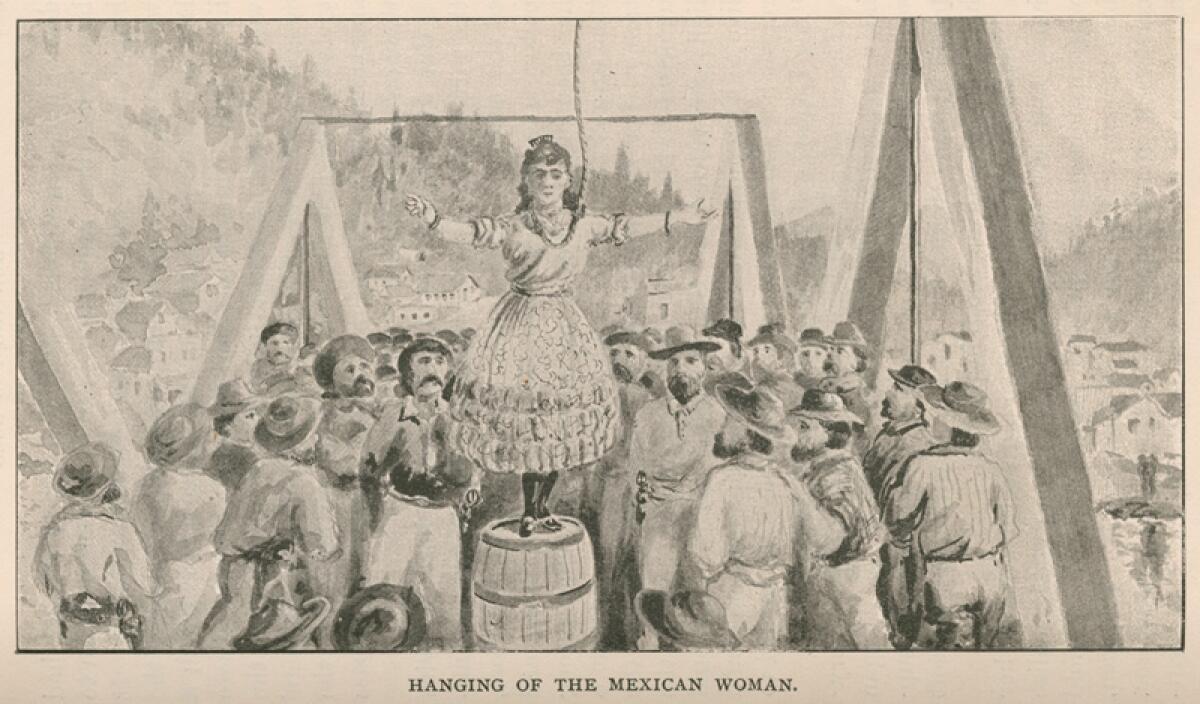

Her face betrayed no fear as she climbed the ladder to a scaffold on a bridge overlooking the Yuba River. The afternoon sun sparkled on the waterway as it wound through pine-shrouded mountains.

The night before, hundreds had celebrated the Fourth of July. Now, they watched, silent, as the woman pushed back two plaits of black hair from her shoulders. She placed the noose around her neck.

When they called for her last words, she declared, fearless, “I would do the same again if I was so provoked.”

Here in this small town in the northern reaches of the Sierra Nevada, the legend of Josefa lives on more than 160 years after her death. Her saga, cobbled together through historical news articles, books and history buffs, is largely unknown even among the state’s Mexican American population but has riveted young and old here in the middle of Trump country.

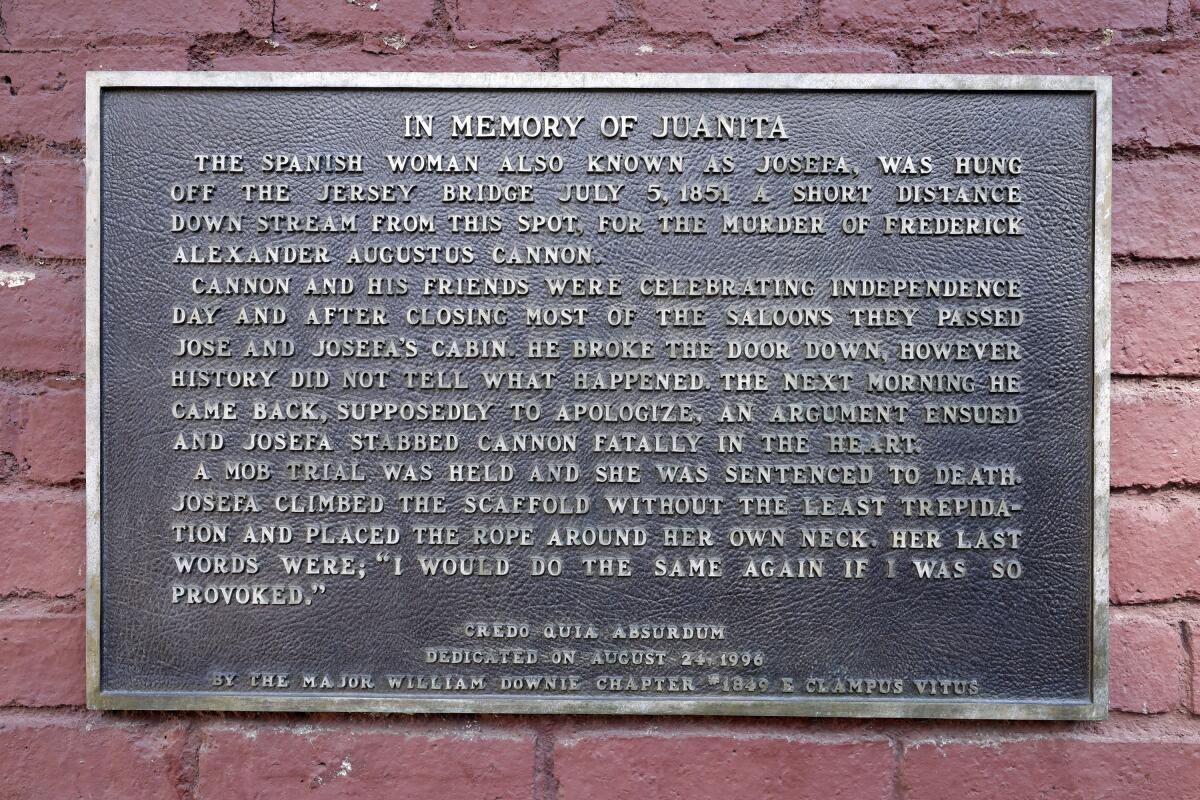

A neighboring town staged a play about Josefa’s trial; an opera in San Francisco gave her a spotlight. A psychic claims to converse with her. But much about her is unknown, including her last name. A plaque commemorating her death refers to her as “Juanita” — a slur people in this gold-mining community once used for any Mexican woman.

Downieville and the surrounding area’s fascination with the story of Josefa predates the era of #MeToo and modern-day hostility toward anyone and anything Mexican, before the El Paso mass shooting and a president conjuring up Mexican “rapists” and drug dealers to get elected. But in their own way, the town’s 200 residents have long debated the role Josefa’s gender and ethnicity played in her fate.

Her story begins soon after this mountain town was founded in 1849.

Only a couple of years had passed since the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which brought an end to the Mexican-American War and gave the modern-day American Southwest to the conquering Yanquis.

Downieville became a bustling Gold Rush town of thousands, most of them men — Mexicans, Chileans, English, French and Chinese. The town had two saw mills and a theater. In letters to his sister, one miner described it as “one of the richest mining towns in the state.”

Josefa was one of the few women living among the miners. The town’s founder, William Downie, said she was known throughout the settlement.

“The lustre in her eyes shone in various degrees, from the soft dove-like expression of a love-sick maiden, to the fierce scowl of an infuriated lioness, according to her temper, which was the only thing not well balanced about her,” Downie wrote after her death.

In the summer of 1851, California celebrated the Fourth of July — the first since becoming a state. The streets of Downieville were filled with parades, bands and heavy drinking.

One of those celebrating was an Australian miner known in news articles and Downie’s book, “Hunting for Gold,” as Cannon. After the festivities, he stumbled down the street before reaching the home Josefa shared with a man named Jose, believed by some to be her husband.

Cannon crashed through the couple’s door. But no one agrees on what happened next.

As an 1851 Marysville Daily Herald newspaper article recounts it, Cannon entered the house and “created a riot and disturbance.” She was so outraged, the article said, that when he arrived the next morning to apologize, she stabbed him in the heart.

But the Steamer Pacific Star, a San Francisco newspaper, had a different version of the story. A doctor said Cannon came to his office about 7 a.m. the day of his death to ask for medicine. While in the doctor’s office, Jose, who lived next door, confronted Cannon about the door.

The two exited the house together, where they were met by Josefa. Soon after, Cannon and Josefa exchanged words in Spanish. The doctor said Cannon offered “pleasant” replies.

Jose later testified that Cannon called him and Josefa names, according to the Steamer Pacific Star account; when Cannon went to enter the house, Josefa stabbed him.

Both Josefa and Jose were taken into custody. Their trial took place the same day.

The Steamer Pacific Star reporter, who described Josefa as pretty, “so far as the style of swarthy Mexican beauty is so considered,” said she “presented more the appearance of one who would confer kindness than one who thirsted for blood.”

The jury found her guilty of murder, and she was ordered to die by hanging — two hours later. Jose was found not guilty but was warned to leave town within 24 hours. As Josefa prepared for her hanging, the Steamer Pacific Star reporter wrote, she extended her hand to those around her and to each said, “Adios, señor.”

◆ ◆ ◆

On a Friday morning this fall, half a dozen students sit in a Downieville Elementary and Junior-Senior High School classroom. They’re taking Spanish online because their teacher is not fluent enough to instruct them himself.

They offer up their own theories.

“Wasn’t she assaulted by him or something and then she killed him out of defense?” a high school student asks.

“I thought she killed him because he cheated on her,” another volunteers.

Most of the students grew up either in the town — which is majority white — or surrounding area, and the versions of the story they’d heard throughout their lives have become muddled as if in a game of telephone.

“What I heard is that some guy grabbed her in the bar and out of defense she stabbed him,” says Esmeralda Nevarez, the school’s student body president.

Two years ago, Esmeralda, who was born in the Mexican state of Durango, wrote a paper for her English class titled, “The Hanging of Juanita.” Esmeralda was drawn to the story of Josefa because of their shared background. The 16-year-old noted in her report — which earned her an A — that racial tension may have been a factor in Josefa’s death.

“The war had just ended and sentiments between Mexicans and all these white settlers that were coming in were pretty bad,” said Maythee Rojas, a professor of Chicano and Latino studies at Cal State Long Beach who has written about Josefa.

“Josefa’s story — how it unfolds and how it is remembered — suggests much about the ways in which Euro-Americans viewed Mexican women in the 19th century,” Rojas wrote in one essay.

After Josefa’s hanging, a few California newspapers said they had hoped the story was fabricated and alluded to the treatment of foreigners.

“The violent proceedings of an indignant and excited mob, led on by the enemies of the unfortunate woman, are a blot upon the history of the State,” one news article stated.

The people responsible for her demise, the newspaper article said, had “shamed themselves and their race.”

◆ ◆ ◆

Downieville, about 100 miles northeast of Sacramento, is gradually shrinking. The population of the Sierra County seat swells during the Downieville Classic Mountain Bike Festival, which draws thousands of riders every summer.

On a recent weekday morning, cyclists visiting for a work retreat zipped past 68-year-old David O’Donnell on $1,000 mountain bikes as he walked along Main Street. He ambled toward a faded green truss bridge near the fork of the Downie and Yuba rivers, where a dozen roses have been strung up with wire since July in remembrance of Josefa. For the better part of 20 years, flowers — or sometimes a noose — have been left behind on this site on the anniversary of her death.

No one knows exactly where she was hanged. Her plaque is affixed to a brick building beside a nearby bridge, but she is believed to have been hanged a short distance downstream.

As some stories go, a local doctor, Cyrus D. Aikin, tried to save Josefa by telling the court that she was pregnant. The doctor was driven from the stand and fled, staying away for a few days for his own safety. Although the doctor died in 1879, at the age of 58, his story passed down among his relatives, eventually reaching his great grand nephew, Bill Reed, a former resident of Downieville.

“Ever since I can remember, I was exceedingly proud that somebody from my family had tried to do the right thing,” the 74-year-old said.

O’Donnell, a lifelong resident of the town and a miner since the age of 12, has never visited the plaque. But he’s familiar with Josefa, that fateful day and its aftermath.

“It sort of put a curse on the town.”

Last year, the graduating class at the town’s K-12 school included just two students. Downieville’s only bank closed in September, and the gas pumps have been out of service for nearly a year. The local theater features about a dozen movies a year and cell service is almost nonexistent.

Every so often, a lumber truck rolls through town. But most of the timber industry died many years ago. Jobs are few, mostly in government. Housing is even more limited than before, ever since residents began renting out summer homes.

The town’s only museum displays a framed front page of a 1921 Mountain Messenger newspaper, which blares: “Come to Sierra County! — for — GOLD!”

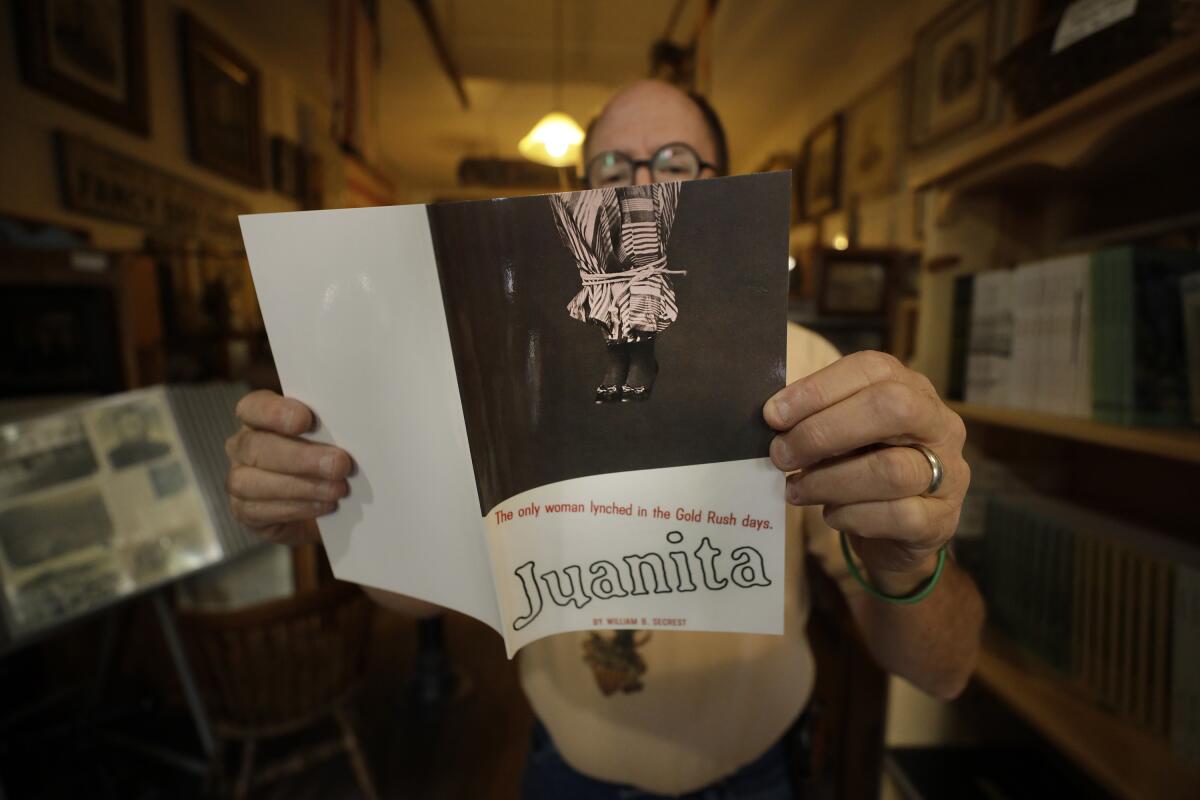

An out-of-print book rests on the third shelf of a bookcase. Its cover reads, “The only woman lynched in the Gold Rush days. Juanita.” On a wall by the door, a small framed drawing shows a woman with a noose around her neck, arms outstretched and her face impassive. It is titled, “Juanita.”

To Jenine Beecher, she is Josefa. The self-proclaimed psychic medium said she met the dead woman three years ago, when Josefa made her presence known by clairvoyantly showing pictures of herself stabbing Beecher as she did laundry.

Josefa did not want to harm her, Beecher recalled, but wanted to channel through her to tell her side of the story. Instead, Beecher asked her to “teach me what you want me to say.”

In her incense-scented home, Beecher grows teary-eyed as she recounts what she refers to as Josefa’s “truth.”

When Cannon entered the home, Beecher said, he made physical advances toward Josefa, prompting her to act in self-defense.

“The energy of the trial was far from fair,” Beecher wrote in a blog post. “To the judge and jury, her act was a display of the uncontrollable and unstable nature of Josefa.”

◆ ◆ ◆

Over drinks in the town’s only bar, Don Russell, the editor-publisher of the Mountain Messenger, California’s oldest weekly newspaper, and self-described contrarian, and Lee Adams, a Sierra County supervisor, recently sparred about the events of 160-plus years ago.

Russell, a Republican until Donald Trump became president, said he doesn’t believe in the death penalty. But he thinks Josefa wrongly killed Cannon.

Adams “thinks it was a bad thing to kill a murderer,” Russell said.

“No, I just think she deserved a fair trial and a legal one,” countered Adams, a former sheriff who considers the matter from a law enforcement point of view.

In the mid-1990s, when Adams hung a sign on the truss bridge in memory of Josefa, Russell replaced it with one in memory of Cannon. A couple of years later, Adams took out a quarter-page ad for Josefa in the paper when Russell was out of town. Russell jokingly sent him a bill for $50,000.

Often, the disagreement among townspeople breaks down by gender lines — creating a “male version and a female version” of the story, as one resident described it. Years ago, Russell’s wife, Irene Frazier, penned an article that ran on the front page of the paper’s Fourth of July edition. She wrote from what she called the “correct perspective,” detailing a drunken man who had broken down a woman’s door.

Frazier dismisses the idea that Cannon had returned to express remorse.

“He was apologizing and bringing her flowers? I don’t think so,” she said.

Russell and his wife at least agree on one thing: “Racism is part of America, period. [Josefa] had no standing in this society,” Russell said. “If she weren’t Spanish or Mexican, any jury would have acquitted her.”

“Nobody knew better then,” Russell said. “Now, everybody knows better.”

Frazier clasped her hands and narrowed her eyes. “Do they?” she asked.

American flags hang outside nearly every store in Downieville, except for La Cocina de Oro — where a Mexican flag is tacked up above the door. A sign in the window reads, “In our America all people are equal.” When she’s been questioned about her lack of an American flag, owner Yvonne Ortiz says she doesn’t need it to show her patriotism.

The restaurant pays homage to Ortiz’s culture, with papel picado strung up in the dining room and a framed poster of the Mexican Revolution — which her grandfather fought in — hanging on the wall. All of her grandparents immigrated from Mexico decades ago, before settling in Southern California.

Ortiz, who opened the restaurant about 10 years ago, arrived as a 22-year-old in the 1970s, when there were even fewer Latinos in town than there are today. She’d been attending Sacramento State and coming up on the weekends. She fell in love with the town.

When she learned of Josefa, she thought of her mother’s mother, named Josefina.

Josefa’s story “was pretty appalling to me,” the 69-year-old said during the dinner rush. “I just thought, what a horrible legacy to have for a town.”

Years ago, she was asked to play Josefa in a Fourth of July parade. Ortiz immediately shut down the idea.

“I don’t want a noose around my neck,” she said at the time.

Nearly two centuries have passed since the execution, but Ortiz can’t help but wonder about the legacy being created today. When she learned that a gunman had killed 22 people, nearly all Mexican nationals or Mexican Americans, in a Walmart in El Paso in August, she responded: “What the … is going on here?”

“I feel like it’s in the air and I never saw it much in the air until Trump came on to be president,” Ortiz said.

President Trump won 14 California counties in 2016 by more than 10 percentage points, all of them in Northern California and the western Sierra. In Downieville, there are stickers on doors and benches touting “Trump No More Bullshit 2020.” On one, someone crossed out “tr” and replaced it with “ch,” spelling “chump.”

The town has become slightly more diverse over the years. The Mexican American manager of the Cold Rush, a cafe and ice cream shop, returned to her hometown after 20 years away. At the Two Rivers cafe, the orders are called out to kitchen workers in Spanish.

Sisters Hillary Lozano and Allison Baca returned permanently in the late 1970s. The women, both white, had grown up in the majority Latino neighborhood of Wilmington in Los Angeles. They went to Downieville for a short time when their mother got a teaching job here.

They both married Mexican American men and started families in L.A. It was fear of violence that drove them back to the small town they liken to the fictional community of Mayberry.

“When we first got here, I don’t think anybody in this town even knew any other Hispanic people,” Baca said. Their older children, the sisters recall, were given a hard time for “being brown.”

The sisters, who are 14 months apart, recall when Lozano’s daughter Michelle was in elementary school and her classmates said she couldn’t join their group because of her dark brown hair.

“They never came out and said ‘it’s because you’re Mexican,’ but it’s because she didn’t have blond hair like the rest of them,” Lozano said.

Everyone in the family knows about Josefa.

On a recent morning, Lozano, 65, sat in the living room of her home along Main Street with her grandson, two daughters, her son-in-law, son and her husband. She asked them what they thought of Josefa’s death.

“She deserved it,” her grandson, Ezra Acuna, said. “Murder is murder.”

“OK, yes. But did she deserve to be lynched?” Lozano responded. The 15-year-old said no.

“Do you think if she’d have been a white woman,” Lozano asked, “that it would’ve been the same?”

Her grandson — a shade of brown like many of his Mexican forebears — was quiet for some time. Finally, he admitted, “I think it would’ve gone differently.”

Times staff writer Scott Wilson contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.