L.A. County and Planned Parenthood to open 50 high school sexual health and well-being centers

- Share via

A high school senior decided recently that she wants to become sexually active with her boyfriend. But she is not yet comfortable talking to her mom about birth control and would be unable to get to a doctor’s appointment on her own. Instead, she walked over to the new well-being center at school during a free period.

It was easy. Planned Parenthood runs a sexual healthcare clinic at Esteban Torres High School in East L.A. once a week. Other days educators are available for stress management and students’ other health concerns, including substance abuse.

The clinic is part of an initiative — funded by the L.A. County departments of public health and mental health and Planned Parenthood Los Angeles — to open 50 such centers in schools throughout the county in the next year.

The effort, which will cost at least $12 million in its first year, is designed to bring much-needed health and wellness care to underserved teenagers at a time when Los Angeles and other districts are struggling to meet the basic needs of their students to help free them to focus on learning.

The high school senior, who asked not to be named to protect her privacy, said that with the clinic’s counseling she decided to start the birth control pill. Without this help, she said, she may not have sought out any expertise.

“It being on campus — there was no excuse not to go,” she said.

The centers include reproductive health clinics where students can get birth control pills and condoms, tests and treatment for sexually transmitted infections, emergency contraception such as Plan B, and pregnancy testing and referrals — services far beyond what is typically offered by school nurses. Planned Parenthood is running five of the 34 sites that are open, offering more extensive birth control options including intrauterine devices and arm implants.

Because California law allows minors older than 12 to obtain confidential treatment and birth control, students can access the services at these clinics without parental consent.

Planned Parenthood hopes to eventually operate all of the clinics and has committed $5 million to the effort over the next five years, said Sue Dunlap, president and chief executive of Planned Parenthood Los Angeles. The county’s public health department is contributing about $10 million in the first year and has committed to keeping the centers open for five years.

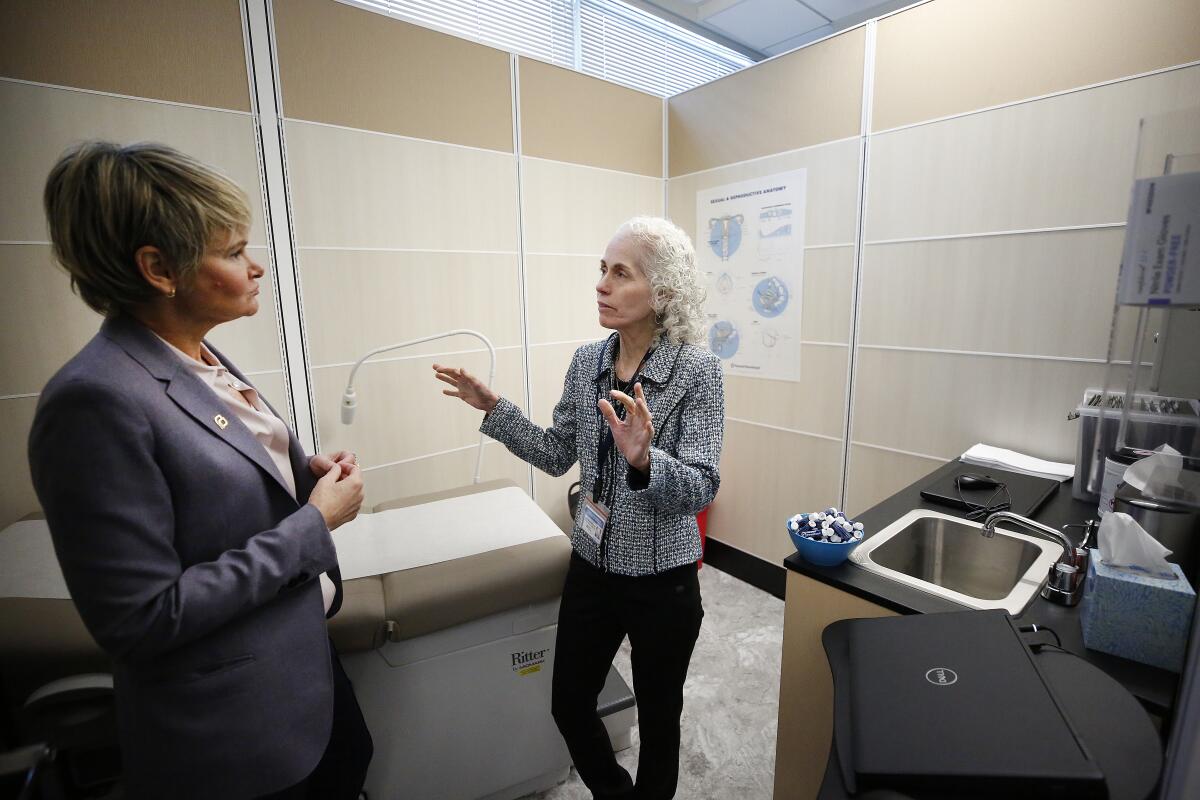

At the Esteban Torres campus, home to five small pilot schools, students can visit the center and clinic that have taken over two rooms behind the main office.

On Fridays, students can see a Planned Parenthood nurse or physician assistant in a “modular clinic” with an exam table, thick makeshift walls and a white noise machine for privacy. Tuesdays through Thursdays, students can visit the well-being center next door, greeted by cute stuffed sloths, with a soft blanket on comfy chairs that are pushed together to resemble a sofa. Signs in the room promise a safe space and an explanation of what defines sexual consent: “Freely given, reversible, informed, enthusiastic, specific.”

All of the centers are staffed at least 20 hours a week by health educators, who have master’s degrees in public health.

The goal is to provide a room to relax and decompress, and to “offer the students another set of caring adults to whom they can come with those strange life questions,” said Billie Dawn Greenblatt, a supervising health educator who oversees three high school sites. She said recent student questions have included: “How do I make a doctor’s appointment?” and “Will vaping hurt my lungs?”

One student asked this week if Greenblatt would help her formulate a plan to come out to her parents; others write anonymous questions on paper slips that she collects, with inquiries like, “Is there a cure for HIV?”

About 30% of L.A. County high school students surveyed reported feeling chronic sadness or hopelessness, according to the state Department of Education’s 2015-2017 California Healthy Kids Survey. For high school students who had recently missed school, 9% of freshmen and 14% of 11th-graders said they were absent because they “felt very sad, hopeless, anxious, stressed, or angry.”

Teenagers may be coping with alcohol, drug use and risky sexual behaviors, and there’s often an overlap between these behaviors and students’ sense that they do not have an adult on campus to talk to, said Barbara Ferrer, the head of the L.A. County Department of Public Health.

About 1 in 5 L.A. County high school students surveyed had alcohol or cannabis in the last month, according to a 2017 survey from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted infection rates have been increasing nationally since 2013, and people ages 15 to 24 accounted for half of gonorrhea and almost a third of chlamydia cases in California last year, though they represent only 20% of the population, according to the California Department of Public Health.

“We have in L.A. County one of the highest rates of chlamydia amongst this age group,” Ferrer said. “These coping strategies impact academic performance as well as their social, emotional, and physical well-being.”

The plan is to open 16 more clinics around L.A. County in the next year to reach the total of 50. These centers are concentrated in communities with high poverty rates and low access to services. Each school community also had to be supportive of a center that would offer reproductive healthcare and long-term birth control on campus, Ferrer said.

The goal, after five years, will be to reduce absenteeism and see a decrease in positive STI tests at the clinics, Ferrer said. The department also wants to try to find a measure of well-being and may expand to look at substance abuse measures if schools show a demand for it.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.