They were planning to run for office. But getting on L.A.’s ballot wasn’t so easy

- Share via

Fitness app owner Adam Summer was ready to wage an aggressive election campaign, one that would have targeted a 10-year incumbent on the Los Angeles City Council.

Caltech researcher Jamie Tijerina was planning her own council bid, hiring a digital media consultant to promote her campaign. And real estate broker Hal Bastian was getting ready to appear onstage at a downtown candidate forum.

All three had their political hopes dashed last month, with city officials informing them they had failed to come up with the 500 voter signatures needed to qualify for the ballot in L.A.’s March 3 election.

Of the 51 people who filed paperwork to run for City Council or school board, 18 of them — more than 35% — did not make it past the signature-gathering process. That’s a greater share of the candidate pool than in any of the city’s last four regular and special elections.

With fewer candidates making the ballot, it’s now more likely that most or even all of L.A.’s council and school board races could be decided in a single round in March, with no runoff in November. Candidates in L.A. contests win outright if they receive more than 50% of the vote, a task that’s easier with a shorter list of contenders.

City Clerk Holly Wolcott, whose office reviewed the petitions, said her staff looked at this year’s high failure rate and found that many candidates turned in fewer signatures than in previous elections — and that a significant number waited until the last minute.

Of the 18 people who did not qualify, 13 submitted their signatures on the day of the filing deadline. That made it impossible for them to go back out and get additional signatures once they fell short.

“The more signatures they turn in up to the limit, the better, and the earlier the better,” Wolcott said.

Bastian, who had been planning to run for the seat being vacated by Councilman Jose Huizar, was one of the would-be candidates whose petitions were turned in on the last day. The downtown resident said he was “heartbroken and angry” to learn that he had failed to make the ballot.

Bastian, 59, said he relied on campaign consultant Michael Trujillo, an experienced hand in L.A. elections, to handle the signature-gathering effort.

“Michael has indicated how sorry he is to me,” he said. “But I will never understand how a 20-year veteran could make a catastrophic error of this kind.”

Trujillo denied that he was responsible for gathering the signatures, saying he was acting as a volunteer, not a paid consultant.

In an email, Trujillo confirmed that he hired political consultant Darrell Alatorre, son of former Councilman Richard Alatorre, to handle signature gathering on Bastian’s behalf. Trujillo said he submitted the petitions to the city clerk as a favor to Bastian — and was simply “being nice.”

“It is ultimately my fault that firm was working on behalf of Hal,” Trujillo wrote. “It’s not my fault they came up short.”

Alatorre did not respond to inquiries about the signature-gathering effort.

Los Angeles sets a high bar for candidates seeking to run for City Council and the L.A. Board of Education. Candidates must pay a fee and turn in at least 500 signatures from people registered to vote in the district where they are running for office. Candidates for state Assembly, state Senate and Congress typically pay a higher fee but need to submit at least 40 valid voter signatures.

For candidates in L.A., gathering those signatures is a “very involved and difficult process,” said political consultant Mike Shimpock, who has handled numerous campaigns in Southern California. Signatures can be thrown out if the signer is not a registered voter, lives in the wrong district or is registered to vote at an address different from the one listed on the petition.

Candidates should try to collect 800 signatures, Shimpock said, to ensure they have enough of a buffer to withstand the vetting process. Because the process is so onerous, well-funded candidates typically have an easier time making it onto the ballot, he added.

“People that have money can hire people to get the signatures,” he said. “But grass-roots people have to be able to build an army of people to get them.”

Candidates in previous L.A. elections had much more success in getting on the ballot, records show. In the 2015 municipal election, 50 people turned in petitions, with 44 qualifying. Two years later, 82 people filed to run for city and school board offices, with 69 making the ballot.

In last year’s special election to replace Eastside school board member Ref Rodriguez, 11 out of 11 people made the cut. (Two others filed petitions but then withdrew from the race.) And 16 out of 17 qualified for the ballot in last year’s special election to replace Councilman Mitchell Englander in the San Fernando Valley, according to tallies from the city clerk’s office.

Some candidates have decided to forge ahead, even after receiving the bad news from the city.

Businesswoman Denise Francis Woods decided to wage a write-in campaign against Councilman Marqueece Harris-Dawson, who represents part of South Los Angeles. Francis Woods and three others turned in petitions to challenge Harris-Dawson last month. All four were found to have insufficient signatures.

Francis Woods, 54, expressed disappointment with the city’s finding but said she is confident her supporters will write in her name when they vote.

“There’s a whole lot of people disappointed that Marqueece is the only one who made it to the ballot,” she said. “So we have a whole lot of energy.”

Tijerina, the Caltech researcher, looked at running as a write-in candidate but decided against it. The fact that so many people failed to make the ballot “means there’s something wrong with the process,” she said.

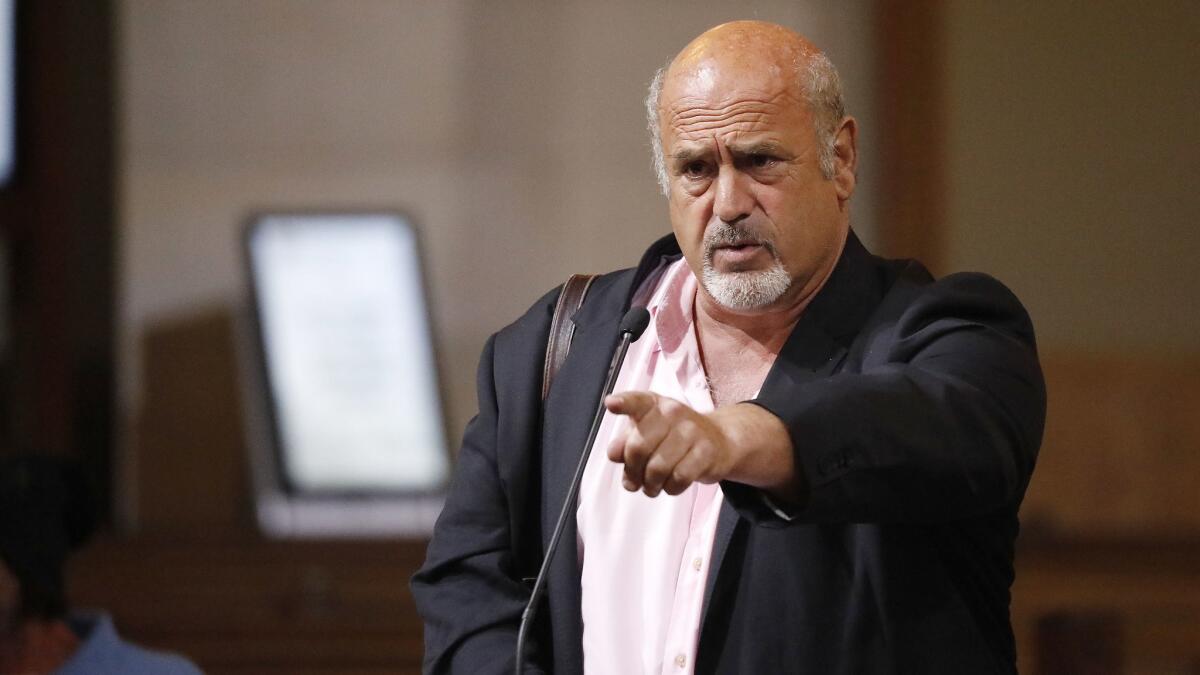

This year’s signature-vetting process even stymied Studio City resident Eric Preven, a longtime City Hall critic who has repeatedly qualified for the ballot in local elections.

Preven, 56, ran unsuccessfully for county supervisor in 2014, City Council in 2015, mayor in 2017 and county supervisor again last year. Last month, he was informed that he lacked sufficient signatures to appear on the March ballot as a candidate for a Valley council seat.

Preven sued the city, demanding that his name be restored, but a judge rejected his request. He is now considering a write-in campaign and says the 500-signature requirement favors elected officials who can afford to hire signature gatherers.

“This is one of many tools in the incumbent-protection program” at City Hall, he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.