As White House takes on ‘sanctuary’ cities, tensions between L.A. County sheriff and ICE ramp up

- Share via

As the White House ramps up its offensive against so-called sanctuary cities, tensions have risen between the Los Angeles County sheriff and Immigration and Customs Enforcement over the federal agency’s operations.

In a wide-ranging interview with The Times last week, Sheriff Alex Villanueva criticized the recent deployment of U.S. Customs and Border Protection officers to help ICE make arrests in “sanctuary” jurisdictions and said he would “shred” subpoenas from the agency that are not signed by a judge.

Villanueva, who promised during his 2018 campaign to end the “pipeline to deportation,” has taken a hard-line stance on ICE — although some immigrant advocates argue he has not done enough to distance himself.

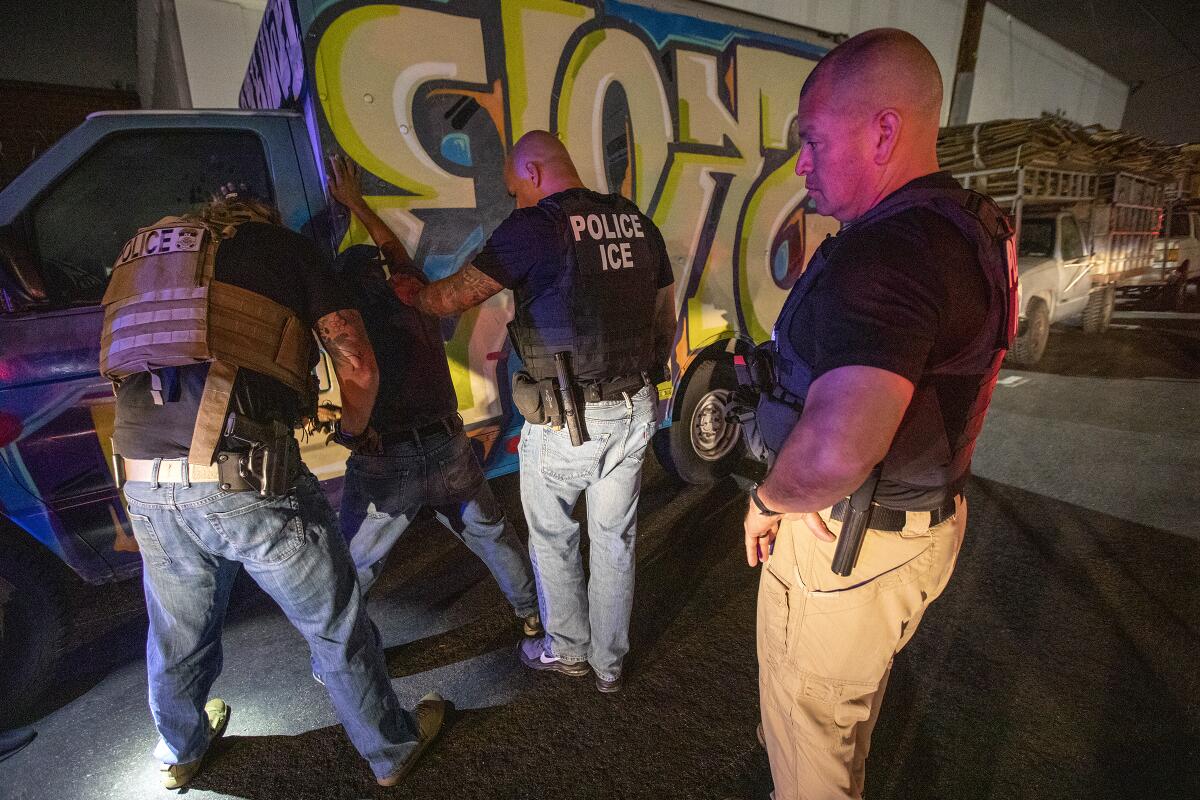

In a recent press briefing, the sheriff said he opposed “SWAT-style agents” helping ICE execute arrests, calling it “overkill” and a form of “weaponizing immigration laws.”

In response, angry ICE officials have accused the sheriff of political grandstanding and of spreading “misinformation.” Last year, ICE was similarly angered over a video in which LAPD Chief Michel Moore stood beside Mayor Eric Garcetti as he told residents they did not have to open their doors for an ICE agent who does not have a warrant signed by a judge

dav

“You’re pitting law enforcement agencies against each other and then forcing the community to make a choice,” said David Marin, the director of Enforcement and Removal Operations for ICE in L.A. “So then the community says, ‘Well, do I have to abide by what ICE says or do I abide by what the sheriff or the chief says?’

“I would never have a press conference and tell people how not to obey a law enforcement agency,” he added. “But then again, I’m a career law enforcement official. I’m not a politician.”

Across the country, relationships between local law enforcement and ICE have only grown more strained as President Trump, who is seeking re-election in November, cracks down on “sanctuary” cities. That is especially true in California, where local law enforcement must abide by a “sanctuary” law, Senate Bill 54, which provides protection for immigrants in the country illegally.

Last month, ICE Director Matthew Albence said that 100 CBP agents and officers would assist in making arrests, including in L.A. and San Francisco, in response to sanctuary-city law enforcement agencies not cooperating with federal authorities by turning over immigrants being held in local jails.

Days later, ICE officers made two arrests at a Northern California courthouse, flouting a state law that requires a judicial warrant to make immigration arrests in those facilities. ICE responded that California law would not govern the conduct of federal officers.

“Our officers will not have their hands tied by sanctuary rules when enforcing immigration laws to remove criminal aliens from our communities,” David Jennings, ICE’s field office director in San Francisco, said in a statement.

The agency also served the San Diego County Sheriff’s Department last month with four administrative subpoenas for information on Mexican nationals wanted for deportation. ICE officials said in a news release that so-called sanctuary laws have essentially forced them to turn to the tactic. Some local officials, in turn, have dug in their heels.

“Administrative subpoenas, you can wrap fish in ‘em,” Villanueva said. “If they route it to a judge and a judge signs it, we honor all subpoenas.”

He called recent actions undertaken by the administration a “show.”

“It’s all about … voters in those red states,” Villanueva said. “Trump is communicating to them that ‘I’m firmly behind you and I support keeping these brown people in the shadows and in fear for their lives.’ … That’s what he thinks his chances for reelection are based on.”

When Villanueva became sheriff, he removed ICE agents from the largest local jail system in the nation and limited the criteria that allow inmates to be transferred to federal custody for possible detention or deportation.

ICE transfers declined by 52% in 2019, according to Villanueva.

While ICE criticizes the sheriff for doing too little, immigrant rights advocates have accused him of not doing enough to distance himself from the federal agency.

Villanueva has been criticized over the fact that inmates are still being delivered to ICE through officers who are contracted by the federal agency.

Immigrants’ rights advocates say transfers are not legally necessary and that it’s unjust to arrest and deport people for civil immigration matters after they’ve already served time for their criminal convictions. In a letter sent to the county Board of Supervisors last week, about 100 immigrant advocacy and criminal justice reform organizations asked that ICE be required to secure a judicial warrant in order to access Sheriff’s Department jail facilities, stations, and courthouse lockups.

“His big promise was to kick ICE out of the jails. For advocates and a lot of us who supported him, that meant no entanglement with ICE,” said Andrés Kwon, a lawyer at the ACLU of Southern California who focuses on immigration issues. “We believe that his policies are really a bait and switch and business as usual.”

Villanueva said that SB 54 “was a balance that the legislators struck” because of competing public safety interests.

“Both sides can try to beat me up, but we’re striking a careful balance,” Villanueva said. “We’re always going to err on the side of what’s best to promote public safety.”

Although Marin cited a good relationship with six of the sheriffs in his area of responsibility, he said that doesn’t exist in L.A. County.

He noted that of the thousands of detainers lodged last year, fewer than 500 people were transferred into ICE custody. As a result, Marin said, ICE officers are forced to make arrests out in the community.

In the L.A. area in fiscal year 2019, ICE made 6,657 administrative arrests, down over a thousand from the year before. Because of staff detailed to the border, ICE had to adjust resources and place fugitive operations officers at detention centers, Marin said, impacting the number of arrests.

That number is nowhere near the numbers of arrests in the area for fiscal year 2014 — which totaled nearly 19,000 — or for fiscal year 2013, which totaled roughly 25,000, although those numbers are likely higher because of agencies that previously honored ICE detainers and did not limit or restrict the agency’s access to jails.

“Here in Southern California there’s a lot of criminal aliens that are being released back out into the community because of sanctuary policies,” Marin said.

Over the past few weeks, fewer than 15 U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents and officers have been working with ICE agents in the L.A. area to help make arrests, according to Marin.

Although some of the CBP agents might be tactical-team certified, they are dressed the same as ICE officers and doing the same work, Marin said. They’ve been trained on ICE processes and operations and are a “force multiplier,” Marin said.

“I think if this is successful, which I’ve seen that it already is, that maybe this is something that we expand,” Marin said. “If we continue to show progress and that this is working, maybe they can afford to keep them with us for two months, three months, four months, six months.”

Times staff writer Maya Lau contributed to this report

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.