Students hit hard as L.A. community colleges scramble to respond to coronavirus

- Share via

On Wednesday morning, Los Angeles Trade Technical College student Milagro Jones logged onto his laptop from a one-bedroom apartment in south Los Angeles to attend an online class on human evolution. His 5-year-old daughter, Lydia, at home from preschool, played nearby.

This was supposed to be the first day of online courses after the Los Angeles Community College District announced it would suspend most in-person classes due to the novel coronavirus.

To Jones’ surprise, nobody else — not even the teacher — was online.

“I didn’t know why,” he said.

At the nation’s largest community college district, communication about the coronavirus has been confusing. Less than half of the faculty had been trained in “distance education” before the pandemic hit. Employees lacked access to systems to enable working from home. There were not enough laptops for students and teachers to access online instruction.

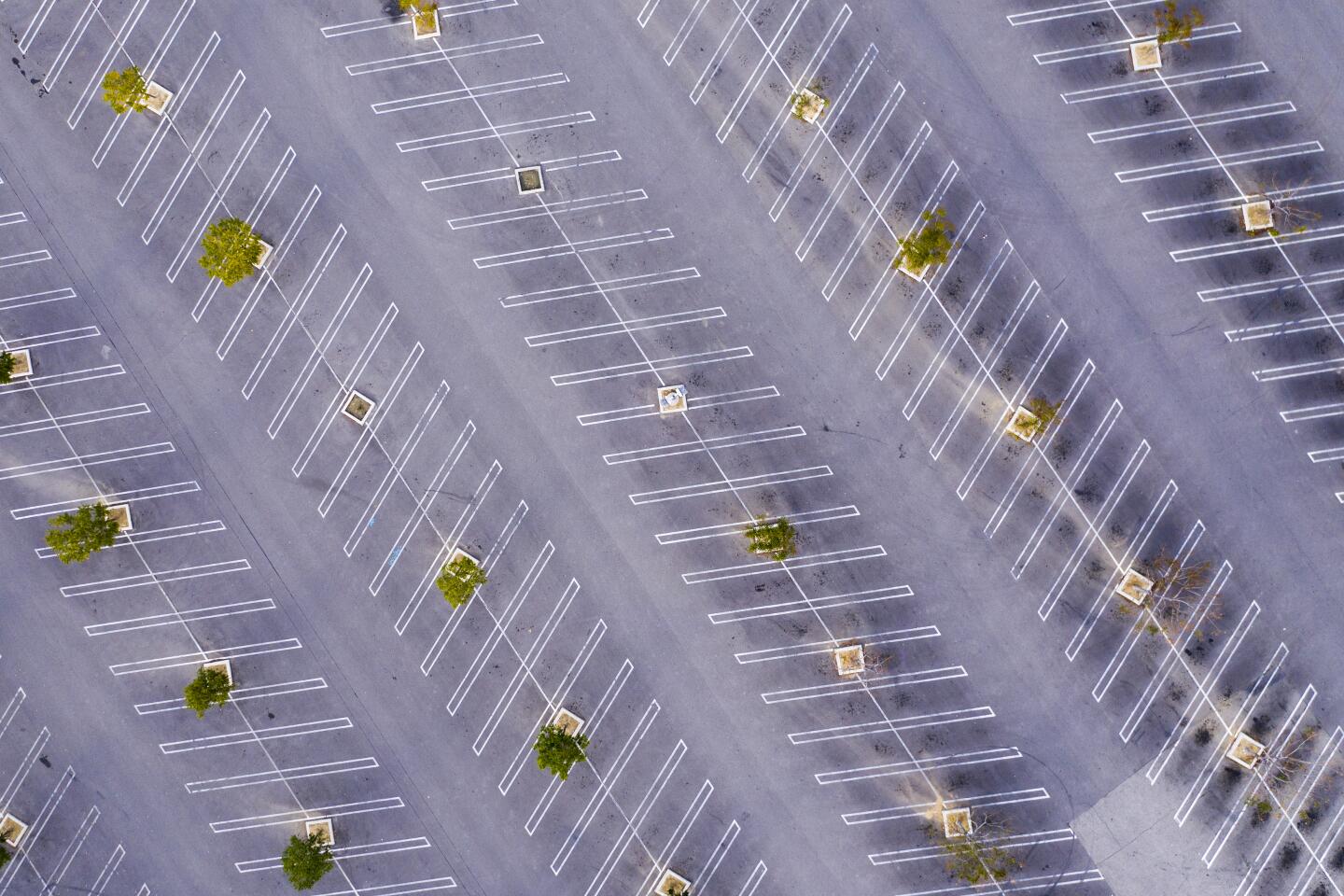

Eerie photos and stunning aerial shots show what California looks like under Gov. Newsom’s “stay at home” order.

Many staff, faculty and students across the nine-college system say the response to the virus has been inadequate.

“We were caught kind of flat-footed,” said Deirdre Wood McDermott, who teaches public speaking and is chair of the language arts and humanities department at Trade Tech. “We’re trying to build the plane while we’re learning to fly.”

The uneven response is disrupting the lives of students who rely on campuses not only for education, but also for essential services such as food, healthcare and help with financial aid forms.

The vast majority of the district’s 230,000 students come from low-income households. Many are food and housing insecure. An estimated one-fourth have children of their own to care for. Their ability to complete their higher education goals is tenuous even under ordinary circumstances.

District officials said they are following their emergency plans and protocols and are regularly pushing out information to students, faculty and staff. But, they said, COVID-19 has created a situation nobody could have planned for.

“This situation that we are in is completely unprecedented,” Chancellor Francisco Rodriguez said. “To say that we have not planned for an emergency is completely false. To say that we have not planned for a pandemic is true.”

California’s landscape of everyday life is changing under the state’s stay-home order. These drone photos prove it.

“We’re changing as the environment is changing,” board president Andra Hoffman said. “It’s been ... a challenge.”

The district created a COVID-19 response team earlier this month to come up with immediate plans of action for health and safety and continuity of operations. Officials have approved $450,000 for supplies and overtime for custodial staff, purchased VPN licenses so more employees can work from home and placed orders for thousands of laptops. They are also rolling out a new platform for online counseling three months ahead of schedule.

Originally administrators said colleges would begin online instruction March 18, but a few days later they voted to cancel classes for a full week and move spring break up in order to give faculty more time before having to begin classes online March 30.

Jones wasn’t aware of that latest change, which was why only he logged on this past Wednesday.

“The response has been confusing,” he said. “I’ve been told different things by different faculty ... You get one thing on email and then it’s different in person.”

Angela Echeverri, president of the district’s academic senate and a microbiology teacher at Mission College, said only about 2,000 of the district’s 5,000 faculty are certified in distance education.

“You can imagine how we’re scrambling here,” she said. “To train 3,000 faculty in a week — I can’t even tell you how overwhelming that is.”

As the coronavirus emergency intensified, with group gatherings restricted, the training itself was forced online.

One counselor showed up for in-person training Monday, where she said she was in a room with 30 to 40 other faculty members, including visibly sick ones, and no hand sanitizer.

Even if faculty and staff can ultimately switch to online education, many students will still struggle.

“Some students view our community colleges as their safe place ... related to where they get their food, to where they get their childcare support, to where they get a sense of safety and comfort,” Rodriguez said. “No matter how well we do ... to provide an online platform, there’s still going to be some dislocation and some trauma that students will experience.”

Teissy Angel, an undocumented “Dreamer” student at Southwest College, works full-time as a caregiver for an adult with intellectual disabilities. She normally gets up around 6 a.m., makes her lunch and goes to campus to attend class. Then she drives to Culver City, where she works from 2 p.m. to 10 p.m. every day.

Angel, 25, has relied on the school library to access expensive textbooks. She also runs a student club that invites local activists and social justice leaders to come talk to students. Most crucially, she helped establish a resource center for “Dreamers” like her on campus, where she would go two or three times a week to use the computers, print course material to read on breaks from her job, and attend workshops on financial aid, legal matters and stress relief.

Though she has a computer and internet at home, “it’s not like I can sit and do all my assignments [at once],” she said. When she can’t pay her internet bill, she resorts to a Starbucks or McDonald’s to use Wi-Fi — but that won’t be an option any more, as patrons can no longer gather at the sites.

“I fear that I’m not going to be able to pass my classes,” said Angel, who is currently on track to transfer to a four-year college in fall 2021. Her professors seem understanding so far.

For some classes, especially in career and technical education, online instruction is simply not possible.

“Ultimately in my areas there’s only so much you can do on paper, only so much you can do online,” William Elarton-Selig, head of the construction, maintenance and utilities department at Trade Tech, said at an emergency Board of Trustees meeting March 14. “You have to be able to drive the nail, you have to be able to screw the parts together ... or [students] won’t have an education that’s of any value to them.”

Meanwhile, clerical and custodial staff said they felt “abandoned” by the administration and unclear on the guidelines of whether and where to work.

“My members were calling me saying, ‘Are we the only ones coming to work today?’” said Steven Butcher, executive secretary of the union that represents clerical and technical staff.

Staff members were particularly worried about having to use sick and vacation days if they stayed home, but district officials said no employees would lose pay or be penalized for staying home due to the coronavirus.

At the core of the emergency, though, are LACC students like Em Owens, 19, of Southwest College, who doesn’t have internet at the studio apartment she shares with her brother in Long Beach. Normally she goes to the library for Wi-Fi, but now she plans to rely on friends’ houses or a mobile hotspot from her phone, which is slow.

Rodriguez said the district is working with internet companies and philanthropists to provide free internet and laptops to students who need them.

And Jones, the single parent who attends Trade Tech, illustrates the struggles — and determination — of many. He has been in and out of homelessness since birth. He got his GED in 2011, while he was incarcerated.

Jones, 30, started at Trade Tech as a full-time student last summer and intends to get an associate degree and transfer to a four-year institution in 2021. His financial aid covers tuition but he is relying on savings and other assistance to cover expenses.

He recently qualified to enroll in a program that comes with a grant to buy books and 20 monthly meal tickets — but now the bookstore and cafeteria are closed. He was hoping to finalize a work-study placement on campus this semester, where he expected to earn $14 an hour, but now that’s on hold, too.

“It’s a hurdle,” he said.

But Jones is undeterred. “I’ve been through a lot in life,” he said. “I’m resourceful, I’m resilient. I’m not gonna let anything hold me back.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.